Spanish Empire

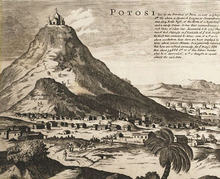

The influx of gold and silver from the mines in Zacatecas and Guanajuato in Mexico and Potosí in Bolivia enriched the Spanish crown and financed military endeavors and territorial expansion.

[18] With the marriage of the heirs apparent to their respective thrones Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile created a personal union that most scholars[citation needed] view as the foundation of the Spanish monarchy.

They successfully pursued expansion in Iberia in the Christian conquest of the Muslim Emirate of Granada, completed in 1492, for which Valencia-born Pope Alexander VI gave them the title of the Catholic Monarchs.

The reign of Ferdinand and Isabella began the professionalization of the apparatus of government in Spain, which led to a demand for men of letters (letrados) who were university graduates (licenciados), of Salamanca, Valladolid, Complutense and Alcalá.

[22] The conquest of the Canary Islands, inhabited by Guanche people, began in 1402 during the reign of Henry III of Castile, by Norman nobleman Jean de Béthencourt under a feudal agreement with the crown.

The War of the Castilian Succession (1475–79) provided the Catholic Monarchs with the opportunity not only to attack the main source of the Portuguese power, but also to take possession of this lucrative commerce.

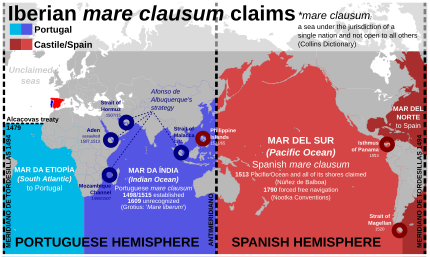

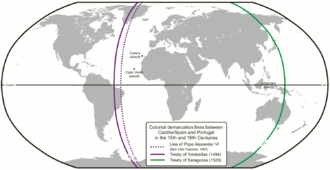

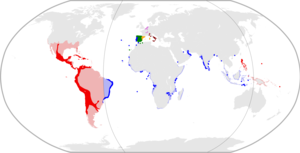

These actions gave Spain exclusive rights to establish colonies in all of the New World from north to south (later with the exception of Brazil, which Portuguese commander Pedro Álvares Cabral encountered in 1500), as well as the easternmost parts of Asia.

On the Atlantic coast, Spain took possession of the outpost of Santa Cruz de la Mar Pequeña (1476) with support from the Canary Islands, and it was retained until 1525 with the consent of the Treaty of Cintra (1509).

[55] Defying the opposition of Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, the governor of Hispaniola, Hernán Cortés organized an expedition of 550 conquistadors and sailed for the coast of Mexico in March 1519.

Philip II of Spain (r. 1556–98) oversaw the colonization of the Philippines, which began in 1565 with the arrival of Spanish explorer Miguel López de Legazpi, making him ruler of one of the first true globe-spanning empires.

The Criollo elites (colonial-born Spaniards) and mestizo and mulatto militia (of mixed Indigenous-Spanish and African-Spanish descent) provided only minimal protection, often assisted by more influential allies with vested interests in maintaining the balance of power and safeguarding the Spanish Empire from falling into enemy hands.

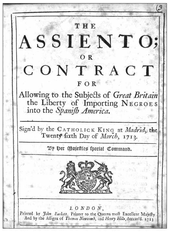

Under the Treaties of Utrecht (11 April 1713) ending the war, the French prince of the House of Bourbon, Philippe of Anjou, grandchild of Louis XIV of France, became King Philip V of Spain.

The presence of other European powers in the Caribbean, with the English in Barbados (1627), St Kitts (1623–25), and Jamaica (1655); the Dutch in Curaçao, and the French in Saint Domingue (Haiti) (1697), Martinique, and Guadeloupe had broken the integrity of the closed Spanish mercantile system and established thriving sugar colonies.

[68][46] At the beginning of his reign, the first Spanish Bourbon, King Philip V, reorganized the government to strengthen the executive power of the monarch as was done in France, in place of the deliberative, Polysynodial System of Councils.

Two upheavals registered unease within Spanish America and at the same time demonstrated the renewed resiliency of the reformed system: the Tupac Amaru uprising in Peru in 1780 and the rebellion of the comuneros of New Granada, both in part reactions to tighter, more efficient control.

[72] Bourbon institutional reforms under Philip V bore fruit militarily when Spanish forces easily retook Naples and Sicily from the Austrians at the Battle of Bitonto in 1734 during the War of the Polish Succession, and during the War of Jenkins' Ear (1739–42) thwarted British efforts to capture the strategic cities of Cartagena de Indias, Santiago de Cuba and St. Augustine by defeating a British combined army and navy force, although Spain's invasion of Georgia also failed.

In 1778, Fernando Pó (now Bioko), adjacent islets, and commercial rights to the mainland between the Niger and Ogooué rivers were ceded to Spain by the Portuguese in exchange for territory in South America (Treaty of El Pardo).

In 1934, during the government of Prime Minister Alejandro Lerroux, Spanish troops led by General Osvaldo Capaz landed in Sidi Ifni and carried out the occupation of the territory, ceded de jure by Morocco in 1860.

In 1958, Spain ceded Tarfaya to Mohammed V and joined the previously separate districts of Saguia el-Hamra (in the north) and Río de Oro (in the south) to form the province of Spanish Sahara.

Supported by large flows of silver from the Americas, trade prohibited by Spanish mercantilist restrictions flourished as it provided a source of income to both crown officials and private merchants.

[92] The crown's pursuit of wars to maintain and expand territory, defend the Catholic faith, stamp out Protestantism, and beat back the Ottoman Turkish strength outstripped its ability to pay for it all, despite the huge production of silver in Peru and New Spain.

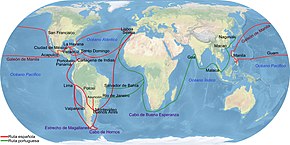

Shipping was through particular ports in Castile: Seville, and subsequently Cádiz, Spanish America: Veracruz, Acapulco, Havana, Cartagena de Indias, and Callao/Lima, and the Philippines: Manila.

But as the Aztec and Inca empires were conquered in the early sixteenth century, and large deposits of silver found in both Mexico and Peru, Spanish immigration increased and the demand for goods rose far beyond Spain's ability to supply it.

Since the crown did not alter its restrictive structure or advocate fiscal prudence, despite the pleas of the arbitristas, the Indies trade remained nominally in the hands of Spain, but in fact enriched the other European countries.

Other European commercial interests came to dominate supply, with Spanish merchant houses and their guilds (consulados) in both Spain and the Indies acting as mere middlemen, reaping a slice of the profits.

As Spain's power weakened in the seventeenth century, England, the Netherlands, and the French took advantage overseas by seizing islands in the Caribbean, which became bases for a burgeoning contraband trade in Spanish America.

Writing in 1738, English author Samuel Johnson questioned, "Has heaven reserved, in pity to the poor,/No pathless waste or undiscovered shore,/No secret island in the boundless main,/No peaceful desert yet unclaimed by Spain?

[112] Hundreds of towns and cities in the Americas were founded during the Spanish rule, with the colonial centers and buildings of many of them now designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites attracting tourists.

The tangible heritage includes universities, forts, cities, cathedrals, schools, hospitals, missions, government buildings and colonial residences, many of which still stand today.

The Old World received from the Americas such things as maize, potatoes, chili peppers, tomatoes, tobacco, beans, squash, cacao (chocolate), vanilla, avocados, pineapples, chewing gum, rubber, peanuts, cashews, Brazil nuts, pecans, blueberries, strawberries, quinoa, amaranth, chia, agave and others.