Christian anarchism

Christian anarchists claim that the state, founded on violence, contravenes the Sermon and Jesus' call to love one's enemies.

[19] The first Christians opposed the primacy of the state: "We must obey God as ruler rather than men" (Acts 4:19, 5:29, 1 Corinthians 6:1-6); "Stripping the governments and the authorities bare, he exhibited them in open public as conquered, leading them in a triumphal procession by means of it."

Also, some early Christian communities appear to have practised anarchist communism, such as the Jerusalem group described in Acts, who shared their money and labour equally and fairly among the members.

[20] Roman Montero claims that using an anthropological framework, such as that of the anarchist David Graeber, one can plausibly reconstruct the communism of the early Christian communities and that the practices were widespread, long-lasting, and substantial.

[19] In his introduction to a translation of the Sayings of the Desert Fathers, Thomas Merton describes the early monastics as "Truly in certain sense 'anarchists', and it will do no harm to think of them as such.

[23] Christianity was then legalized under the Edict of Milan in 313, which hastened the Church's transformation from a humble bottom-up sect to an authoritarian top-down organization.

The communities failed following a crackdown by the English authorities, but a series of pamphlets by Winstanley survived, of which The New Law of Righteousness (1649) was the most important.

In Germany its foremost spokesman during the Peasant Wars was Thomas Müntzer; in England, Gerrard Winstanley, a leading participant in the Digger movement.

The concepts held by Müntzer and Winstanley were superbly attuned to the needs of their time – a historical period when the majority of the population lived in the countryside and when the most militant revolutionary forces came from an agrarian world.

What is of real importance is that they spoke to their time; their anarchist concepts followed naturally from the rural society that furnished the bands of the peasant armies in Germany and the New Model in England.

"[27] The 19th-century Christian abolitionists Adin Ballou and William Lloyd Garrison were critical of all human governments and believed that they would be eventually supplanted by a new order in which individuals are guided solely by their love for God.

Ballou remained a lifelong pacifist and condemned the Civil War for fear of the eventual retaliation by white southerns on freed black Americans.

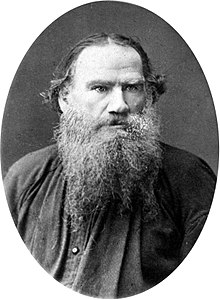

[7] Tolstoy sought to separate Russian Orthodox Christianity, which was merged with the state, from what he believed was the true message of Jesus as contained in the Gospels, specifically in the Sermon on the Mount.

[40] Peter Maurin's vision to transform the social order consisted of establishing urban houses of hospitality to care for the destitute, rural farming communities to teach city dwellers agrarianism and encourage a movement back to the land, and roundtable discussions in community centres to clarify thought and initiate action.

[45][46][47] Christian anarchists, such as David Lipscomb, Leo Tolstoy, Ammon Hennacy, Jacques Ellul, and Dave Andrews, follow Jesus' call to not resist evil but turn the other cheek.

[3] They believe freedom will only be guided by the grace of God if they show compassion to others and turn the other cheek when confronted with violence.

To illustrate how nonresistance works in practice, Alexandre Christoyannopoulos offers the following Christian anarchist response to terrorism: The path shown by Jesus is a difficult one that can only be trod by true martyrs.

[52] Romans 13:1–7 holds the most explicit reference to the state in the New Testament but other parallel texts include Titus 3:1, Hebrews 13:17 and 1 Peter 2:13-17.

"[57][58] Christian anarchists and pacifists such as Jacques Ellul and Vernard Eller do not attempt to overthrow the state given Romans 13 and Jesus' command to turn the other cheek.

However Christian anarchists point out an inconsistency if this text were to be taken literally and in isolation as Jesus and Paul were both executed by the governing authorities or "rulers" even though they did "right.

"[55] There are also Christians anarchists such as Leo Tolstoy and Ammon Hennacy, who favor Jesuism and do not see the need to integrate Paul's teachings into their subversive way of life.

Tolstoy, Adin Ballou and Petr Chelčický understand this to mean that Christians should never bind themselves to any oath as they may not be able to fulfil the will of God if they are bound to the will of a fellow-man.

[66][67] Adin Ballou wrote that if the act of resisting taxes requires physical force to withhold what a government tries to take, then it is important to submit to taxation.

Ammon Hennacy, who, like Ballou also believed in nonresistance, eased his conscience by simply living below the income tax threshold.

Leo Tolstoy, Ammon Hennacy, and Théodore Monod extended their belief in nonviolence and compassion to all living beings through vegetarianism.

Therefore, when we take any part in government by voting for legislative, judicial, and executive officials, we make these men our arm by which we cast a stone and deny the Sermon on the Mount.

Pope John Paul II granted the Archdiocese of New York permission to open Day's cause for sainthood in March 2000, calling her a Servant of God.

In literature, in Michael Paraskos's 2017 novel, Rabbitman, a political satire prompted by Donald Trump's presidency, the heroine, called Angela Witney, is a member of an imagined Catholic Worker commune located in the southern English village of Ditchling, where the artist Eric Gill once lived.

[81] Numerous Christian anarchist websites, social networking sites, forums, electronic mailing lists and blogs have emerged on the internet over the last few years.

Christians often cite Romans 13 as evidence that the State should be obeyed,[84] while secular anarchists reject belief in any authority including God.