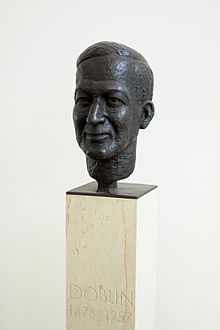

Alfred Döblin

Döblin would live in Berlin for almost all of the next forty-five years, engaging with such key figures of the prewar and Weimar-era German cultural scene as Herwarth Walden and the circle of Expressionists, Bertolt Brecht, and Thomas Mann.

[9] His parents' marriage dissolved in July 1888, when Max Döblin eloped with Henriette Zander, a seamstress twenty years his junior, and moved to America to start a new life.

Furthermore, his oppositional tendencies against the stern conventionality of the patriarchal, militaristic Wilhelminian educational system, which stood in contrast to his artistic inclinations and his free thought, earned him the status of a rebel among his teachers.

[18] He applied for assistantships in Berlin and in Stettin, where he was apparently turned down on account of his Jewish origins,[19] before taking a short-lived position as assistant doctor at a regional asylum in Regensburg.

[22] Despite his continued involvement with Kunke, at the urging of his family he was reluctantly engaged to Reiss on 13 February 1911 and married her on 23 January 1912; his older brother Hugo and Herwarth Walden served as best men.

[27] The novel portrays the developing sexuality of its protagonist, Johannes, and explores the themes of love, hate, and sadism; in its use of literary montage, The Black Curtain already presages the radical techniques that Döblin would later pioneer in Berlin Alexanderplatz.

[28] Introduced by a mutual acquaintance, Döblin met Georg Lewin, a music student better known as Herwarth Walden, who founded the Expressionist journal Der Sturm in 1910.

Der Sturm, modeled after Karl Kraus's newspaper Die Fackel (The Torch), would soon count Döblin among its most involved contributors, and provided him with a venue for the publication of numerous literary and essayistic contributions.

At regular meetings at the Café des Westens on Kurfürstendamm or at the wine bar Dalbelli, Döblin got to know the circle of artists and intellectuals that would become central to the Expressionist movement in Berlin, including Peter Hille, Richard Dehmel, Erich Mühsam, Paul Scheerbart, and Frank Wedekind, among others.

Döblin had to interrupt work on the novel in March 1917 because he had caught typhus, but was able to use the university library at Heidelberg during his convalescence in April and May to continue researching the Thirty Years' War.

Back in Saargemünd he came into conflict with his superiors due to the poor treatment of the patients; on 2 August 1917 he was transferred to Hagenau (Haguenau) in Alsace, where the library of nearby Strassbourg helped complete Wallenstein by the beginning of 1919.

[42] The same year, following a family vacation to the Baltic coast, he began preparatory work on his science fiction novel Berge Meere und Giganten (Mountains Seas and Giants), which would be published in 1924.

[45] At the end of September 1924, he set out on a two-month trip through Poland, subsidized by the Fischer Verlag and prompted in part by the anti-Semitic pogroms in Berlin's Scheunenviertel of 1923, an event that awakened Döblin's interest in Judaism.

[57] Döblin's closest acquaintances during this time were Claire and Yvan Goll, Hermann Kesten, Arthur Koestler, Joseph Roth, Hans Sahl, and Manès Sperber.

[63] With other writers, he met with President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the White House, and saw his old Berlin acquaintance Ernst Toller again, who was suffering from severe depression and killed himself shortly thereafter.

[69] Döblin worked briefly for Metro Goldwyn Mayer writing screenplays for $100 a week, but his contract expired in October 1941 and was not renewed, despite the interventions of Thomas Mann and others.

[73] Döblin was embittered by his isolation and setbacks in exile, drawing a strong distinction between his own situation and that of more successful writers less oppressed by material concerns, such as Lion Feuchtwanger and Thomas Mann.

Heinrich Mann gave a speech, Fritz Kortner, Peter Lorre, and Alexander Granach read aloud from Döblin's works, and he was presented with notes of congratulation and praise from Brecht, Max Horkheimer, and Alfred Polgar, among others.

Yet the festivities were dampened when Döblin gave a speech in which he mentioned his conversion to Catholicism; the religious, moral tone proved alienating, and fell on unsympathetic ears.

That spring had brought the good news that Klaus was alive and in Switzerland after a period working for the French resistance, and the grim tidings that Wolfgang was dead, having committed suicide five years to avoid being captured by troops of the Wehrmacht.

[81] His last novel, Hamlet oder Die lange Nacht nimmt ein Ende (Tales of a Long Night), was published in 1956, and was favorably received.

[82] Döblin's remaining years were marked by poor health (he had Parkinson's disease) and lengthy stays in multiple clinics and hospitals, including his alma mater, Freiburg University.

Through the intervention of Theodor Heuss and Joachim Tiburtius, he was able to receive more money from the Berlin office in charge of compensating victims of Nazi persecution; this, and a literary prize from the Mainz Academy in the sum of 10,000 DM helped finance his growing medical expenses.

Following the dissipation of this endeavor, he suffers a breakdown and finally flees the country, eloping aboard a steamship bound for America that is powered by the steam turbines of his victorious competitor.

[96] Döblin's 1924 science fiction novel recounts the course of human history from the 20th to the 27th century, portraying it as a catastrophic global struggle between technological mania, natural forces, and competing political visions.

Berge Meere und Giganten (Mountains Seas and Giants) presciently invokes such topics as urbanization, the alienation from nature, ecological devastation, mechanization, the dehumanization of the modern world, as well as mass migration, globalization, totalitarianism, fanaticism, terrorism, state surveillance, genetic engineering, synthetic food, the breeding of humans, biochemical warfare, and others.

A village priest declares that Manas and the demons make up a single new terrible being: likely meaning a human no longer innocent but equipped with Id, Ego and Superego.

[113] His writing is characterized by an innovative use of montage and perspectival play, as well as what he dubbed in 1913 a "fantasy of fact" ("Tatsachenphantasie")—an interdisciplinary poetics that draws on modern discourses ranging from the psychiatric to the anthropological to the theological, in order to "register and articulate sensory experience and to open up his prose to new areas of knowledge.

"[114] His engagement with such key movements of the European avant-garde as futurism, expressionism, dadaism, and Neue Sachlichkeit has led critic Sabina Becker to call him "perhaps the most significant representative of literary modernism in Berlin.

C. D. Godwin, Chinese University Press, Hong Kong, 1991), and the November 1918 trilogy: A People Betrayed (which also includes The Troops Return) and Karl and Rosa (trans.