David Bohm

David Joseph Bohm FRS[1] (/boʊm/; 20 December 1917 – 27 October 1992) was an American scientist who has been described as one of the most significant theoretical physicists of the 20th century[2] and who contributed unorthodox ideas to quantum theory, neuropsychology and the philosophy of mind.

[5] Bohm warned of the dangers of rampant reason and technology, advocating instead the need for genuine supportive dialogue, which he claimed could bridge and unify conflicting and troublesome divisions in the social world.

He then transferred to the theoretical physics group directed by Robert Oppenheimer at the University of California, Berkeley Radiation Laboratory, where he obtained his doctorate.

Bohm lived in the same neighborhood as some of Oppenheimer's other graduate students (Giovanni Rossi Lomanitz, Joseph Weinberg, and Max Friedman) and with them became increasingly involved in radical politics.

[11] During World War II, the Manhattan Project mobilized much of Berkeley's physics research in the effort to produce the first atomic bomb.

According to biographer F. David Peat,[12] "The scattering calculations (of collisions of protons and deuterons) that he had completed proved useful to the Manhattan Project and were immediately classified.

[15] Bohm then left for Brazil to assume a professorship of physics at the University of São Paulo, at Jayme Tiomno's invitation and on the recommendation of both Einstein and Oppenheimer.

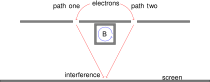

[18] Bohm's aim was not to set out a deterministic, mechanical viewpoint but to show that it was possible to attribute properties to an underlying reality, in contrast to the conventional approach.

He was in contact with Brazilian physicists Mário Schenberg, Jean Meyer, Leite Lopes, and had discussions on occasion with visitors to Brazil, including Richard Feynman, Isidor Rabi, Léon Rosenfeld, Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker, Herbert L. Anderson, Donald Kerst, Marcos Moshinsky, Alejandro Medina, and the former assistant to Heisenberg, Guido Beck, who encouraged him in his work and helped him to obtain funding.

His work with Vigier was the beginning of a long-standing cooperation between the two and Louis De Broglie, in particular, on connections to the hydrodynamics model proposed by Madelung.

[23] Yet the causal theory met much resistance and skepticism, with many physicists holding the Copenhagen interpretation to be the only viable approach to quantum mechanics.

In 1957, Bohm and his student Yakir Aharonov published a new version of the Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen (EPR) paradox, reformulating the original argument in terms of spin.

[3][32][33] In the view of Bohm and Hiley, "things, such as particles, objects, and indeed subjects" exist as "semi-autonomous quasi-local features" of an underlying activity.

In that picture, the classical limit for quantum phenomena, in terms of a condition that the action function is not much greater than the Planck constant, indicates one such criterion.

[4][failed verification] Bohm worked with Pribram on the theory that the brain operates in a manner that is similar to a hologram, in accordance with quantum mathematical principles and the characteristics of wave patterns.

[41][42] An examination in 2017 of the relationship between the two men presents it in a more positive light and shows that Bohm's work in the psychological field was complementary to and compatible with his contributions to theoretical physics.

[37] The mature expression of Bohm's views in the psychological field was presented in a seminar conducted in 1990 at the Oak Grove School, founded by Krishnamurti in Ojai, California.

[37][43] Bohm maintains that thought is a system, in the sense that it is an interconnected network of concepts, ideas and assumptions that pass seamlessly between individuals and throughout society.

In his book Science, Order and Creativity, Bohm referred to the views of various biologists on the evolution of the species, including Rupert Sheldrake.

Bohm temporarily even held Uri Geller's bending of keys and spoons to be possible, prompting warning remarks by his colleague Basil Hiley that it might undermine the scientific credibility of their work in physics.

Martin Gardner reported this in a Skeptical Inquirer article and also critiqued the views of Jiddu Krishnamurti, with whom Bohm had met in 1959 and had had many subsequent exchanges.

An essential ingredient in this form of dialogue is that participants "suspend" immediate action or judgment and give themselves and each other the opportunity to become aware of the thought process itself.

His final work, the posthumously published The Undivided Universe: An Ontological Interpretation of Quantum Theory (1993), resulted from a decades-long collaboration with Basil Hiley.

He also spoke to audiences across Europe and North America on the importance of dialogue as a form of sociotherapy, a concept he borrowed from London psychiatrist and practitioner of Group Analysis Patrick de Maré, and he had a series of meetings with the Dalai Lama.