Alhambra Decree

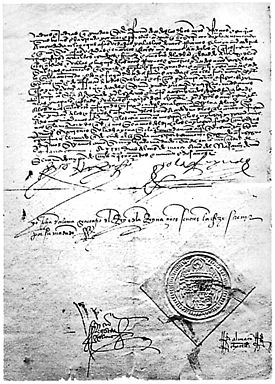

The Alhambra Decree (also known as the Edict of Expulsion; Spanish: Decreto de la Alhambra, Edicto de Granada) was an edict issued on 31 March 1492, by the joint Catholic Monarchs of Spain (Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon) ordering the expulsion of practising Jews from the Crowns of Castile and Aragon and its territories and possessions by 31 July of that year.

[1] The primary purpose was to eliminate the influence of practising Jews on Spain's large formerly-Jewish converso New Christian population, to ensure the latter and their descendants did not revert to Judaism.

An unknown number of the expelled eventually succumbed to the pressures of life in exile away from formerly-Jewish relatives and networks back in Spain, and so converted to Roman Catholicism to be allowed to return in the years following expulsion.

[5]:17 In 1924, the regime of Primo de Rivera granted Spanish citizenship to a part of the Sephardic Jewish diaspora, though few people benefited from it in practice.

In 2015, the government of Spain passed a law allowing dual citizenship to Jewish descendants who apply, to "compensate for shameful events in the country's past".

[4] Under Islamic law, the Jews, who had lived in the region since at least Roman times, were considered "People of the Book" and treated as dhimmi, which was a protected status.

[12] Compared to the repressive policies of the Visigothic Kingdom, who, starting in the sixth century had enacted a series of anti-Jewish statutes which culminated in their forced conversion and enslavement, the tolerance of the Muslim Moorish rulers of al-Andalus allowed Jewish communities to thrive.

Although Jews never enjoyed equal status to Muslims, in some Taifas, such as Granada, Jewish men were appointed to very high offices, including that of Grand vizier.

[14] As the Reconquista drew to a close, overt hostility against Jews in Christian Spain became more pronounced, finding expression in brutal episodes of violence and oppression.

In the early fourteenth century, the Christian kings vied to prove their piety by allowing the clergy to subject the Jewish population to forced sermons and disputations.

[4] More deadly attacks came later in the century from mobs of angry Catholics, led by popular preachers, who would storm into the Jewish quarter, destroy synagogues, and break into houses, forcing the inhabitants to choose between conversion and death.

By the mid-15th century, the demands of the Old Christians that the Catholic Church and the monarchy differentiate them from the conversos led to the first limpieza de sangre laws, which restricted opportunities for converts.

Their marriage in 1469, which formed a personal union of the crowns of Aragon and Castile, with coordinated policies between their distinct kingdoms, eventually led to the final unification of Spain.

Although their initial policies towards the Jews were protective, Ferdinand and Isabella were disturbed by reports claiming that most Jewish converts to Christianity were insincere in their conversion.

Jews and conversos played an important role during this campaign because they had the ability to raise money and acquire weapons through their extensive trade networks.

[4] Finally, in 1491 in preparation for an imminent transition to Castilian territory, the Treaty of Granada was signed by Emir Muhammad XII and the Queen of Castile, protecting the religious freedom of the Muslims there.

"[1] In practice, however, the Jews had to sell anything they could not carry: their land, their houses, and their libraries, and converting their wealth to a more portable form proved difficult.

Concerning this incident, Bayezid II is alleged to have commented, "those who say that Ferdinand and Isabella are wise are indeed fools; for he gives me, his enemy, his national treasure, the Jews."

About 600 Jewish families were allowed to stay in Portugal following an exorbitant bribe until the Portuguese king entered negotiations to marry the daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella.

Such figures exclude the significant number of Jews who returned to Spain due to the hostile reception they received in their countries of refuge, notably Fes (Morocco).

Similarly the Provision of the Royal Council of 24 October 1493 set harsh sanctions for those who slandered these New Christians with insulting terms such as tornadizos.

Of the 100,000 Jews that remained true to their faith by 1492, an additional number chose to convert and join the converso community rather than face expulsion.

Recent conversos were subject to additional suspicion by the Inquisition, which had been established to persecute religious heretics, but in Spain and Portugal was focused on finding crypto-Jews.

Additionally, Limpieza de sangre statutes instituted legal discrimination against converso descendants, barring them from certain positions and forbidding them from emigrating to the Americas.

[6] As stated above, the Alhambra decree was officially revoked in 1968, after the Second Vatican Council rejected the charge of deicide traditionally attributed to the Jews.

In 1992, in a ceremony marking the 500th anniversary of the Edict of Expulsion, King Juan Carlos (wearing a yarmulke) prayed alongside Israeli president Chaim Herzog and members of the Jewish community in the Beth Yaacov Synagogue.

Goldschläger and Orjuela have explored motivations to request citizenship and the ways in which legal provisions, religious associations, and the migration industry become gatekeepers of and (re)shape what it means to be Sephardic.