Alkylating antineoplastic agent

Goodman, Gilman, and others began studying nitrogen mustards at Yale in 1942, and, following the sometimes dramatic but highly variable responses of experimental tumors in mice to treatment, these agents were first tested in humans late that year.

Use of methyl-bis (beta-chloroethyl) amine hydrochloride (mechlorethamine, mustine) and tris (beta-chloroethyl) amine hydrochloride for Hodgkin's disease lymphosarcoma, leukemia, and other malignancies resulted in striking but temporary dissolution of tumor masses.

[2] These publications spurred rapid advancement in the previously non-existent field of cancer chemotherapy, and a wealth of new alkylating agents with therapeutic effect were discovered over the following two decades.

In fact, animal and human trials had begun the previous year, Gilman makes no mention of such an episode in his recounting of the early trials of nitrogen mustards,[4] and the marrow-suppressing effects of mustard gas had been known since the close of World War I.

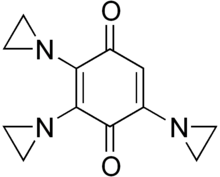

[3] Some alkylating agents are active under conditions present in cells; and the same mechanism that makes them toxic allows them to be used as anti-cancer drugs.

If the two guanine residues are in the same strand, the result is called limpet attachment of the drug molecule to the DNA.

Platinum-based chemotherapeutic drugs (termed platinum analogues) act in a similar manner.

Cross-linking of double-stranded DNA by alkylating agents is inhibited by the cellular DNA-repair mechanism, MGMT.

Methylation of the MGMT promoter in gliomas is a useful predictor of the responsiveness of tumors to alkylating agents.