River ecosystem

The mean flow rate vector is based on the variability of friction with the bottom or sides of the channel, sinuosity, obstructions, and the incline gradient.

Fast, turbulent streams expose more of the water's surface area to the air and tend to have low temperatures and thus more oxygen than slow, backwaters.

Oxygen can be limiting if circulation between the surface and deeper layers is poor, if the activity of lotic animals is very high, or if there is a large amount of organic decay occurring.

[15] The inorganic substrate of lotic systems is composed of the geologic material present in the catchment that is eroded, transported, sorted, and deposited by the current.

[6] Typically, substrate particle size decreases downstream with larger boulders and stones in more mountainous areas and sandy bottoms in lowland rivers.

[10] Substrate can also be organic and may include fine particles, autumn shed leaves, large woody debris such as submerged tree logs, moss, and semi-aquatic plants.

Streams have numerous types of biotic organisms that live in them, including bacteria, primary producers, insects and other invertebrates, as well as fish and other vertebrates.

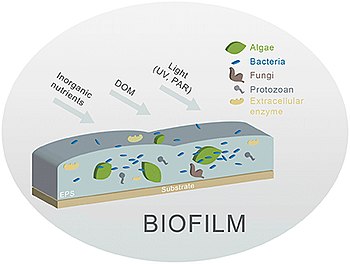

Free-living forms are associated with decomposing organic material, biofilm on the surfaces of rocks and vegetation, in between particles that compose the substrate, and suspended in the water column.

The EPS immobilize the cells and keep them in close proximity allowing for intense interactions including cell-cell communication and the formation of synergistic consortia.

Both the biofilm physical structure, and the plasticity of the organisms that live within it, ensure and support their survival in harsh environments or under changing environmental conditions.

[6] Algae and plants are important to lotic systems as sources of energy, for forming microhabitats that shelter other fauna from predators and the current, and as a food resource.

[26] In addition to these behaviors and body shapes, insects have different life history adaptations to cope with the naturally-occurring physical harshness of stream environments.

[citation needed] Additional invertebrate taxa common to flowing waters include mollusks such as snails, limpets, clams, mussels, as well as crustaceans like crayfish, amphipoda and crabs.

Salmon, for example, are anadromous species that are born in freshwater but spend most of their adult life in the ocean, returning to fresh water only to spawn.

[6] Other vertebrate taxa that inhabit lotic systems include amphibians, such as salamanders, reptiles (e.g. snakes, turtles, crocodiles and alligators) various bird species, and mammals (e.g., otters, beavers, hippos, and river dolphins).

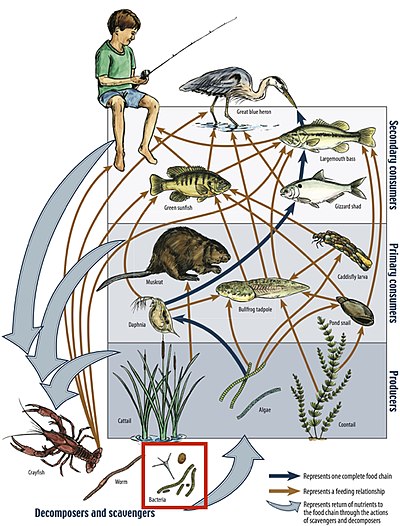

Algae contributes to a lot of the energy and nutrients at the base of the food chain along with terrestrial litter-fall that enters the stream or river.

[37] Energy and nutrients that starts with primary producers continues to make its way up the food chain and depending on the ecosystem, may end with these predatory fish.

[5] Members of the gatherer-collector guild actively search for FPOM under rocks and in other places where the stream flow has slackened enough to allow deposition.

In these cases, a combination of factors such as historical rates of speciation and extinction, type of substrate, microhabitat availability, water chemistry, temperature, and disturbance such as flooding seem to be important.

[6] Although many alternate theories have been postulated for the ability of guild-mates to coexist (see Morin 1999), resource partitioning has been well documented in lotic systems as a means of reducing competition.

Tropical fishes in Borneo, for example, have shifted to shorter life spans in response to the ecological niche reduction felt with increasing levels of species richness in their ecosystem (Watson and Balon 1984).

[6] On shorter time scales, however, flow variability and unusual precipitation patterns decrease habitat stability and can all lead to declines in persistence levels.

Microbial decomposition should play the largest role in energy production for low-ordered sites and large rivers, while photosynthesis, in addition to degraded allochthonous inputs from upstream will be essential in mid-ordered systems.

As mid-ordered sites will theoretically receive the largest variety of energy inputs, they might be expected to host the most biological diversity (Vannote et al.

Despite its shortcomings, the RCC remains a useful idea for describing how the patterns of ecological functions in a lotic system can vary from the source to the mouth.

Junk in 1989, further modified by P. B. Bayley in 1990 and K. Tockner in 2000, takes into account the large amount of nutrients and organic material that makes its way into a river from the sediment of surrounding flooded land.

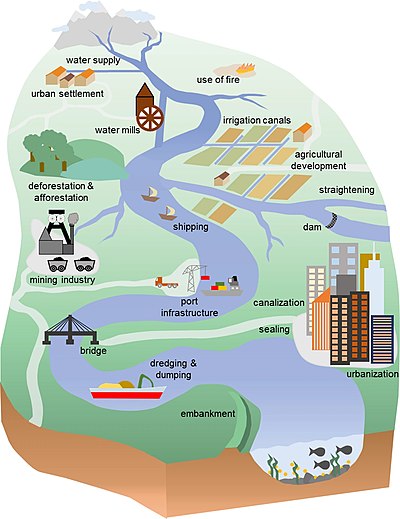

While direct pollution of lotic systems has been greatly reduced in the United States under the government's Clean Water Act, contaminants from diffuse non-point sources remain a large problem.

Urban and residential areas can also add to this pollution when contaminants are accumulated on impervious surfaces such as roads and parking lots that then drain into the system.

Elevated nutrient concentrations, especially nitrogen and phosphorus which are key components of fertilizers, can increase periphyton growth, which can be particularly dangerous in slow-moving streams.

[5] Finally, dams fragment river systems, isolating previously continuous populations, and preventing the migrations of anadromous and catadromous species.