Almohad doctrine

These policies affected large parts of the Maghreb and altered the existing religious climate in al-Andalus (Islamic Spain and Portugal) for many decades.

[4][5] They marked a major departure from the social policies and attitudes of earlier Muslim governments in the region, including the preceding Almoravid dynasty which had followed its own reformist agenda.

Ibn Tumart claimed to be the mahdi, a title which elevated him to something similar to a messiah or leader of a redemption of righteous Islamic order.

He and his successors had very different personalities from Ibn Tumart but nonetheless pursued his reforms, culminating in a particularly aggressive push by Ya'qub al-Mansur (who arguably ruled at the apogee of Almohad power in the late 12th century).

[1]: 255–258 The Almohad ideology preached by Ibn Tumart is described by Amira Bennison as a "sophisticated hybrid form of Islam that wove together strands from Hadith science, Zahiri and Shafi'i fiqh, Ghazalian social actions (hisba), and spiritual engagement with Shi'i notions of the imam and mahdi".

Central to his philosophy, Ibn Tumart preached a fundamentalist or radical version of tawhid – referring to a strict monotheism or to the "oneness of God".

[citation needed] They primarily followed the Zahiri school of fiqh within Sunni Islam; under the reign of Abu Yaqub Yusuf, chief judge Ibn Maḍāʾ oversaw the banning of any religious material written by non-Zahirites.

[11] In terms of Islamic theology, the Almohads were Ash'arites, their Zahirite-Ash'arism giving rise to a complicated blend of literalist jurisprudence and esoteric dogmatics.

Although Ibn Rushd (who was also an Islamic judge) saw rationalism and philosophy as complimentary to religion and revelation, his views failed to convince the traditional Maliki ulema, with whom the Almohads were already at odds.

[24] It was obligatory in the khuṭba to repeat the "Almohad creed," with blessings upon the Mahdi Ibn Tumart and affirmation of his claimed hidāya and prophetic lineage.

[1]: 173–174 Jews, however, were particularly vulnerable as they faced an uncertain minority status in both Christian or Muslim territory, as well as because they lived mainly in urban areas where they were especially visible to authorities.

Even the famous Jewish philosopher Maimonides was reported to have officially converted to Islam under Almohad rule when he moved from Cordoba to Fes, before finally leaving for Egypt where he was able to live openly as a Jew again.

[1]: 174 Half-hearted oaths were certainly not looked to as ideal and brought a lot of problems for the population of al-Andalus, much as it did during the forced conversion of Muslims and Jews in Spain and Portugal a few centuries later.

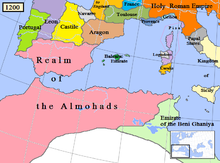

[27] In al-Andalus the Almohad caliphate was decisively defeated by the combined Christian forces of Portugal, Castile, and Aragon at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, in 1212.

Not only was it a decisive defeat of the Muslim forces, it was also one of the first times the fractured Christian kingdoms of the north came together for the common goal of reclaiming the peninsula.

Some scholars consider that Ibn Tumart's overall ideological mission ultimately failed, but that, like the Almoravids, his movement nonetheless played a role in the history of Islamization in the region.

[29] The Hafsids of Tunisia, in turn, officially declared themselves the true "Almohads" after their independence from Marrakesh but this identity and ideology lessened in importance over time.

[2] After 1311, when Sultan al-Lihyani took power with Aragonese help, Ibn Tumart's name was dropped from the khutba (the main community sermon on Fridays), effectively signaling the end of public support for Almohad doctrine.