Paleolithic dog

Previously in 1969, a study of ancient mammoth-bone dwellings at the Mezine paleolithic site in the Chernigov region, Ukraine uncovered 3 possibly domesticated "short-faced wolves".

[3][4] In 2002, a study looked at 2 fossil skulls of large canids dated at 16,945 years before present (YBP) that had been found buried 2 metres and 7 metres from what was once a mammoth-bone hut at the Upper Paleolithic site of Eliseevichi-1 in the Bryansk region of central Russia, and using an accepted morphologically based definition of domestication declared them to be "Ice Age dogs".

[5] In 2009, another study looked at these 2 early dog skulls in comparison to other much earlier but morphologically similar fossil skulls that had been found across Europe and concluded that the earlier specimens were "Paleolithic dogs", which were morphologically and genetically distinct from Pleistocene wolves that lived in Europe at that time.

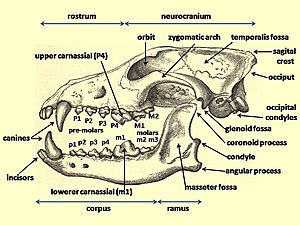

The snout width was greater than those of both the Pleistocene and modern wolves, and implies well-developed carnassials driven by powerful jaws.

The study proposes that the proto-dogs consumed more bone along with other less desirable food scraps within human camps, therefore this may be evidence of early dog domestication.

These include a number of specimens from Germany (Kniegrotte, Oelknitz, Teufelsbrucke), Switzerland (Monruz, Kesslerloch, Champre-veyres-Hauterive), as well as Ukraine (Mezin, Mezhirich).

A set of specimens dating 15,000–13,500 YBP have been confidently identified as domesticated dogs, based on their morphology and the archaeological sites in which they have been found.

Attempting to identify early tamed wolves, wolfdogs, or proto-dogs through morphological analysis alone may be impossible without the inclusion of genetic analyses.

[18] The early domestication theory argues that the relationship commenced once humans moved into the colder parts of Eurasia around 35,000 YBP, which is when the proposed Paleolithic dogs first began to appear.

[6][27][59] Wolves that were adjusting to live with humans may have developed shorter, wider skulls and more steeply-rising foreheads that would make wolf facial expressions easier to interpret.

The study proposes that changes in morphology across time and how humans were interacting with the species in the past needs to be considered in addition to these two techniques.

The study looked at the 2 Eliseevichi-1 dog skulls in comparison to much earlier Late Pleistocene but morphologically similar fossil skulls that had been found across Europe, and proposed the much earlier specimens were Paleolithic dogs that were morphologically and genetically distinct from the Pleistocene wolves living in Europe at that time.

Several skulls of fossil large canids from sites in Belgium, Ukraine and Russia were examined using multivariate analysis to look for evidence of the presence of Paleolithic dogs that were separate from Pleistocene wolves.

Collagen analysis indicated that the Paleolithic dogs associated with human hunter-gatherer camp-sites (Eliseevichi-1, Mezine and Mezhirich) had been specifically eating reindeer, while other predator species in those locations and times had eaten a range of prey.

For one skull, "a large bone fragment is present between the upper and lower incisors that extends several centimetres into the mouth cavity.

[70] There has been ongoing debate in the scientific press about what the fossil remains of the Paleolithic dog might be, with some commenters declaring them as either wolves or a unique form of wolf.

[74] In 2016, a study proposed that dogs may have been domesticated separately in both Eastern and Western Eurasia from two genetically distinct and now extinct wolf populations.

[33] In 2011, a study looked at the well-preserved 33,000-year-old skull and left mandible of a dog-like canid that was excavated from Razboinichya Cave in the Altai Mountains of southern Siberia (Central Asia).

The morphology was compared to the skulls and mandibles of large Pleistocene wolves from Predmosti, Czech Republic, dated 31,000 YBP, modern wolves from Europe and North America, and prehistoric Greenland dogs from the Thule period (1,000 YBP or later) to represent large-sized but unimproved fully domestic dogs.

"The Razboinichya Cave cranium is virtually identical in size and shape to prehistoric Greenland dogs" and not the ancient nor modern wolves.

The Razboinichya Cave specimen appears to be an incipient dog...and probably represents wolf domestication disrupted by the climatic and cultural changes associated with the Last Glacial Maximum".

The haplotype groups closest to the Altai dog included such diverse breeds as the Tibetan mastiff, Newfoundland, Chinese crested, cocker spaniel and Siberian husky.

The sequence strongly suggests a position at the root of a clade uniting two ancient wolf genomes, two modern wolves, as well as two dogs of Scandinavian origin.

[25] Ecological factors including habitat type, climate, prey specialization and predatory competition will greatly influence wolf genetic population structure and cranio-dental plasticity.

[5] Based on cranial morphometric study of the characteristics thought to be associated with the domestication process, these have been proposed as early Paleolithic dogs.

[72] These characteristics of shortened rostrum, tooth crowding, and absence or rotation of premolars have been documented in both ancient and modern wolves.