Patio process

Smelting, or refining, is most often necessary because silver is only infrequently found as a native element like some metals nobler than the redox couple 2 H+ + 2 e−⇌ H2 (gold, mercury, ...).

[1] The process, which uses mercury amalgamation to recover silver from ore, was first used at scale by Bartolomé de Medina in Pachuca, Mexico, in 1554.

He was approached during his research by an unknown German man, known only as "Maestro Lorenzo," who told him that silver could be extracted from ground ores using mercury and a salt-water brine.

Medina is generally credited with adding "magistral" (a type of copper sulfate CuSO4 derived from pyrites) to the mercury and salt-water (H2O · NaCl) solution in order to catalyze the amalgamation reaction.

"[11] The amalgamation was so efficient that a refiner could turn a profit even if the ores were poor enough to yield only 1.5 oz of silver per 100 lbs of original material.

[13] The harina was then placed in heaps of 2,000 lbs or more, to which was added salt, water, magistral (essentially an impure form of copper sulfate, CuSO4), and mercury.

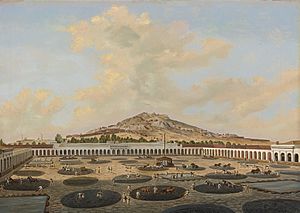

This was then mixed by bare-legged Indian laborers or by horses or mules and spread in a 1-to-2-foot-thick (0.30 to 0.61 m) layer in a patio (a shallow-walled, open enclosure).

After six to eight weeks of mixing and soaking in the sun, a complex reaction converted the silver to native metal, which formed an amalgam with the mercury.

The decision of how much of each ingredient to add, how much mixing was needed, and when to halt the process depended on the skill of an azoguero (English: quicksilver man).

In addition, places that were rich in ore but too isolated from indigenous populations or forests for the labor- and fuel-intensive smelting method to be profitable, as was the case with Potosí in modern-day Bolivia, were now viable.

Spaniards tended to distrust naboríos and accused them of profiteering by stealing ore, taking advances and fleeing, or contracting themselves out to multiple employers at a time.

Thirteen thousand draft laborers per year worked at the largest mine in the Americas, located at Potosí in modern Bolivia.

[37] The rapid expansion of silver production and coinage—made possible due to the invention of amalgamation—has often been identified as the primary driver of the price revolution, a period of high inflation lasting from the sixteenth to early seventeenth-century in Europe.

Proponents of this theory argue that Spain's reliance on silver coins from the Americas to finance its large balance of payments deficits resulted in a general expansion of the European money supply and corresponding inflation.