Sumo

'striking one another')[1] is a form of competitive full-contact wrestling where a rikishi (wrestler) attempts to force his opponent out of a circular ring (dohyō) or into touching the ground with any body part other than the soles of his feet (usually by throwing, shoving or pushing him down).

Many ancient traditions have been preserved in sumo, and even today the sport includes many ritual elements, such as the use of salt purification, from Shinto.

[4] Despite this setback, sumo's popularity and general attendance has rebounded due to having multiple yokozuna (or grand champions) for the first time in a number of years and other high-profile wrestlers grabbing the public's attention.

The written word goes back to the expression sumai no sechi (相撲の節), which was a wrestling competition at the imperial court during the Heian period.

Prehistoric wall paintings indicate that sumo originated from an agricultural ritual dance performed in prayer for a good harvest.

[6] The first mention of sumo can be found in a Kojiki manuscript dating back to 712, which describes how possession of the Japanese islands was decided in a wrestling match between the kami known as Takemikazuchi and Takeminakata.

Regular events at the Emperor's court, the sumai no sechie, and the establishment of the first set of rules for sumo fall into the cultural heyday of the Heian period.

[6][9] By the Muromachi period, sumo had fully left the seclusion of the court and became a popular event for the masses, and among the daimyō it became common to sponsor wrestlers.

Because several bouts were to be held simultaneously within Oda Nobunaga's castle, circular arenas were delimited to hasten the proceedings and to maintain the safety of the spectators.

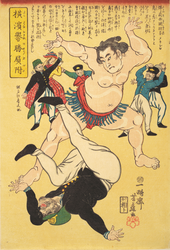

When Matthew Perry was shown sumo wrestling during his 1853 expedition to Japan, he found it distasteful and arranged a military showcase to display the merits of Western organization.

Due to a new fixation on Western culture, sumo had come to be seen as an embarrassing and backward relic, and internal disputes split the central association.

[13] Illegal moves are called kinjite, which include strangulation, hair-pulling, bending fingers, gripping the crotch area, kicking, poking eyes, punching and simultaneously striking both the opponent's ears.

The dohyō, which is constructed and maintained by the yobidashi, consists of a raised pedestal on which a circle 4.55 m (14.9 ft) in diameter is delimited by a series of rice-straw bales.

If the match has not yet ended after the allotted time has elapsed, a mizu-iri (water break) is taken, after which the wrestlers continue the fight from their previous positions.

This prompted 16-year-old Takeji Harada of Japan (who had failed six previous eligibility tests) to have four separate cosmetic surgeries over a period of 12 months to add an extra 15 cm (6 in) of silicone to his scalp, which created a large, protruding bulge on his head.

[21] In response to this, the JSA stated that they would no longer accept aspiring wrestlers who surgically enhanced their height, citing health concerns.

They are also not allowed to enter the wrestling ring (dohyō), a tradition stemming from Shinto and Buddhist beliefs that women are "impure" because of menstrual blood.

[32] The 2018 film The Chrysanthemum and the Guillotine depicts female sumo wrestlers at the time of civil unrest following the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake.

Since 1958, six Grand Sumo tournaments or honbasho have been held each year: three at the Kokugikan in Tokyo (January, May, and September), and one each in Osaka (March), Nagoya (July), and Fukuoka (November).

This colorful name for the culmination of the tournament echoes the words of the playwright Zeami to represent the excitement of the decisive bouts and the celebration of the victor.

A winning wrestler in the top division may receive additional prize money in envelopes from the referee if the matchup has been sponsored.

On entering sumo, they are expected to grow their hair long to form a topknot, or chonmage, similar to the samurai hairstyles of the Edo period.

[16] The most common type of lunch served is the traditional sumo meal of chankonabe, which consists of a simmering stew of various meat and vegetables cooked at the table, and usually eaten with rice.

[38] In the afternoon, the junior wrestlers again usually have cleaning or other chores, while their sekitori counterparts may relax, or deal with work issues related to their fan clubs.

[39][40] Many develop type 2 diabetes or high blood pressure, and they are prone to heart attacks due to the enormous amount of body mass and fat that they accumulate.

[38][43][41] As of 2024[update], the monthly salary figures (in Japanese yen) for the top two divisions (sekitori) are:[44] San'yaku wrestlers also receive a relatively small additional tournament allowance, depending on their rank, and yokozuna receive an additional allowance every second tournament, associated with the making of a new tsuna belt worn in their ring entering ceremony.

Wrestlers lower than the second-highest division are considered trainees, and they receive only a fairly small monthly allowance instead of a salary (as junior wrestlers live in sumo stables, most if not all of their living expenses, such as but not limited to a living space, food, electricity, and other general amenities, are covered by the stables): Prize money is given to the winner of each divisional championship: In addition to prizes for a divisional championship, wrestlers in the top makuuchi division below the rank of ōzeki giving an exceptional performance in the eyes of a judging panel can also receive one or more of three special prizes (the sanshō), which are worth ~¥2 million (about US$13000) each.

Most new entries into professional sumo are junior high school graduates with little to no previous experience,[47] but the number of wrestlers with a collegiate background in the sport has been increasing over the past few decades.

Amateur sumo clubs are gaining in popularity in the United States, with competitions regularly being held in major cities across the country.

[52] A small number of Brazilian wrestlers have made the transition to professional sumo in Japan, including Ryūkō Gō and Kaisei Ichirō.