North American English regional phonology

Regional dialects in North America are historically the most strongly differentiated along the Eastern seaboard, due to distinctive speech patterns of urban centers of the American East Coast like Boston, New York City, and certain Southern cities, all of these accents historically noted by their London-like r-dropping (called non-rhoticity), a feature gradually receding among younger generations, especially in the South.

Outside of the Eastern seaboard, virtually all other North American English (both in the U.S. and Canada) has been firmly rhotic (pronouncing all r sounds), since the very first arrival of English-speaking settlers.

The interior and western half of the country was settled by people who were no longer closely connected to England, living farther from the British-influenced Atlantic Coast.

Certain particular vowel sounds are the best defining characteristics of regional North American English including any given speaker's presence, absence, or transitional state of the so-called cot–caught merger.

One phenomenon apparently unique to North American U.S. accents is the irregular behavior of words that in the British English standard, Received Pronunciation, have /ɒrV/ (where V stands for any vowel).

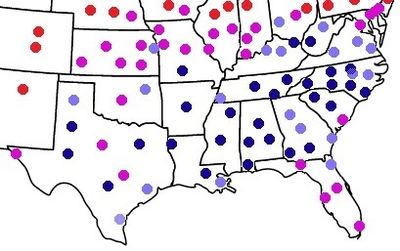

The broadest regional dialects include: Combining information from the phonetic research through interviews of Labov et al. in the ANAE (2006) and the phonological research through surveys of Vaux (2004), Hedges (2017) performed a latent class analysis (cluster analysis) to generate six clusters, each with American English features that naturally occurred together and each expected to match up with one of these six broad U.S. accent regions: the North, the South, the West, New England, the Midland, and the Mid-Atlantic (including New York City).

[34][35] The English dialect region encompassing the Western United States and Canada is the largest one in North America and also the one with the fewest distinctive phonological features.

The English of the Pacific Northwest, a region extending from British Columbia south into the Northwestern United States (particularly Washington and Oregon), is closely linguistically related to that of Inland Canada and that of California.

The vowels of cot [kɑ̈t] and caught [kɔət] are distinct; in fact the New York dialect has perhaps the highest realizations of /ɔ/ in North American English, even approaching [oə] or [ʊə].

New York City and its surrounding areas are also known for a complicated[citation needed] short-a split into lax [æ] versus tense [eə], so that words, for example, like cast, calf, and cab have a different, higher, tenser vowel sound than cat, catch, and cap.

The Inland North is a dialect region once considered the home of "standard Midwestern" speech that was the basis for General American in the mid-20th century.

However, the Inland North dialect has been modified in the mid-1900s by the Northern Cities Vowel Shift (NCS), which is now the region's main outstanding feature, though it has been observed to be reversing at least in some areas, in particular with regards to /æ/ raising before non-nasal consonants and /ɑ/ fronting.

[6][7] The Inland North is centered on the area on the U.S. side of the Great Lakes, most prominently including central and western New York State (including Syracuse, Binghamton, Rochester, and Buffalo), much of Michigan's Lower Peninsula (Detroit, Grand Rapids), Toledo, Cleveland, Chicago, Gary, and southeastern Wisconsin (Milwaukee, Racine, Kenosha), but broken up by the city of Erie, whose accent today is non-Inland Northern and even Midland-like.

New England does not form a single unified dialect region, but rather houses as few as four native varieties of English, with some linguists identifying even more.

Indeed, Rhode Island shares with New York and Philadelphia an unusually high and back allophone of /ɔ/ (as in caught), even compared to other communities that do not have the cot–caught merger.

Southwestern New England merely forms a "less strong" extension of the Inland North dialect region, and it centers on Connecticut and western Massachusetts.

It shows the same general phonological system as the Inland North, including variable elements of Northern Cities Vowel Shift (NCS)—for instance, an /æ/ that is somewhat higher and tenser than average, an /ɑ/ that is fronter than /ʌ/, and so on.

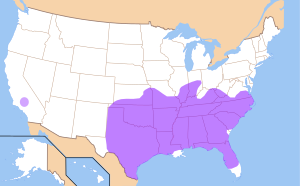

[47] These are the minimal necessary features that identify a speaker from the Southeastern super-region: A band of the United States from Pennsylvania west to the Great Plains is what twentieth-century linguists identified as the "Midland" dialect region, though this dialect's same features are now reported in certain other pockets of the country too (for example, some major cities in Texas, all in Central and South Florida, and particular cities that are otherwise Southern).

The /æ/ phoneme (as in cat) shows most commonly a so-called "continuous" distribution: /æ/ is raised and tensed toward [eə] before nasal consonants, as in much of the country.

Atlanta, Georgia has been characterized by a massive movement of non-Southerners into the area during the 1990s, leading the city to becoming hugely mixed in terms of dialect.

Charleston was once home to its own very locally-unique accent that encompassed elements of older British English while resisting Southern regional accent trends, perhaps with additional linguistic influence from French Huguenots, Sephardi Jews, and, due to Charleston's high concentration of African-Americans that spoke the Gullah language, Gullah African Americans.

The most distinguishing feature of this now-dying accent is the way speakers pronounce the name of the city, to which a standard listener would hear "Chahlston", with a silent "r".

In South Florida, particularly in and around Miami-Dade, Broward, and Monroe counties, a unique dialect, commonly called the "Miami accent", is widely spoken.

[58] The Mid-Atlantic split of /æ/ into two separate phonemes, similar to but not exactly the same as New York City English, is one major defining feature of the dialect region, as is a resistance to the Mary–marry–merry merger and cot-caught merger (a raising and diphthongizing of the "caught" vowel), and a maintained distinction between historical short o and long o before intervocalic /r/, so that, for example, orange, Florida, and horrible have a different stressed vowel than story and chorus; all of these features are shared between Mid-Atlantic American and New York City English.

Pronunciations of the Southern dialect in Texas may also show notable influence derived from an early Spanish-speaking population or from German immigrants.

[citation needed] The Yat/NYC parallels include the split of the historic short-a class into tense [eə] and lax [æ] versions, as well as pronunciation of cot and caught as [kɑ̈t] and [kɔət].

One of the most detailed phonetic depictions of an extreme "yat" accent of the early 20th century is found in the speech of the character Krazy Kat in the comic strip of the same name by George Herriman.

[61] St. Louis resists the cot–caught merger and middle-aged speakers show the most advanced stages of the NCS,[51] while maintaining many of the other Midland features.

The merger has also spread from Western Pennsylvania into adjacent West Virginia, historically in the South Midland dialect region.

The city of Pittsburgh shows an especially advanced subset of Western Pennsylvania English, additionally characterized by a sound change that is unique in North America: the monophthongization of /aʊ/ to [a].