American English

[22] Full rhoticity (or "R-fulness") is typical of American accents, pronouncing the phoneme /r/ (corresponding to the letter ⟨r⟩) in all environments, including in syllable-final position or before a consonant, such as in pearl, car and fort.

Moreover, American accents preserve /h/ at the start of syllables, while perhaps a majority of the regional dialects of England participate in /h/ dropping, particularly in informal contexts.

American English speakers have integrated traditionally non-English terms and expressions into the mainstream cultural lexicon; for instance, en masse, from French; cookie, from Dutch; kindergarten from German,[79] and rodeo from Spanish.

[80][81][82][83] Landscape features are often loanwords from French or Spanish, and the word corn, used in England to refer to wheat (or any cereal), came to denote the maize plant, the most important crop in the U.S.

Due to Mexican culinary influence, many Spanish words are incorporated in general use when talking about certain popular dishes: cilantro (instead of coriander), queso, tacos, quesadillas, enchiladas, tostadas, fajitas, burritos, and guacamole.

The names of some American inventions remained largely confined to North America (elevator [except in the aeronautical sense], gasoline) as did certain automotive terms (truck, trunk).

[citation needed] New foreign loanwords came with 19th and early 20th century European immigration to the U.S.; notably, from Yiddish (chutzpah, schmooze, bupkis, glitch) and German (hamburger, wiener).

[90] Examples of nouns that are now also verbs are interview, advocate, vacuum, lobby, pressure, rear-end, transition, feature, profile, hashtag, head, divorce, loan, estimate, X-ray, spearhead, skyrocket, showcase, bad-mouth, vacation, major, and many others.

Compounds coined in the U.S. are for instance foothill, landslide (in all senses), backdrop, teenager, brainstorm, bandwagon, hitchhike, smalltime, and a huge number of others.

Many compound nouns have the verb-and-preposition combination: stopover, lineup, tryout, spin-off, shootout, holdup, hideout, comeback, makeover, and many more.

Americanisms formed by alteration of some existing words include notably pesky, phony, rambunctious, buddy, sundae, skeeter, sashay and kitty-corner.

Adjectives that arose in the U.S. are, for example, lengthy, bossy, cute and cutesy, punk (in all senses), sticky (of the weather), through (as in "finished"), and many colloquial forms such as peppy or wacky.

Terms such as fall ("autumn"), faucet ("tap"), diaper ("nappy"; itself unused in the U.S.), candy ("sweets"), skillet, eyeglasses, and obligate are often regarded as Americanisms.

[8][94] Other words and meanings were brought back to Britain from the U.S., especially in the second half of the 20th century; these include hire ("to employ"), I guess (famously criticized by H. W. Fowler), baggage, hit (a place), and the adverbs overly and presently ("currently").

[95][96][97] Linguist Bert Vaux created a survey, completed in 2003, polling English speakers across the United States about their specific everyday word choices, hoping to identify regionalisms.

[98] The study found that most Americans prefer the term sub for a long sandwich, soda (but pop in the Great Lakes region and generic coke in the South) for a sweet and bubbly soft drink,[99] you or you guys for the plural of you (but y'all in the South), sneakers for athletic shoes (but often tennis shoes outside the Northeast), and shopping cart for a cart used for carrying supermarket goods.

Often, these differences are a matter of relative preferences rather than absolute rules; and most are not stable since the two varieties are constantly influencing each other,[100] and American English is not a standardized set of dialects.

"[101] Other differences are due to the francophile tastes of the 19th century Victorian era Britain (for example they preferred programme for program, manoeuvre for maneuver, cheque for check, etc.).

The regional sounds of present-day American English are reportedly engaged in a complex phenomenon of "both convergence and divergence": some accents are homogenizing and leveling, while others are diversifying and deviating further away from one another.

However, the South, Inland North, and a Northeastern coastal corridor passing through Rhode Island, New York City, Philadelphia, and Baltimore typically preserve an older cot–caught distinction.

[107] For that Northeastern corridor, the realization of the THOUGHT vowel is particularly marked, as depicted in humorous spellings, like in tawk and cawfee (talk and coffee), which intend to represent it being tense and diphthongal: [oə].

[113] A split of TRAP into two separate phonemes, using different a pronunciations for example in gap [æ] versus gas [eə], further defines New York City as well as Philadelphia–Baltimore accents.

The only traditional r-dropping (or non-rhoticity) in regional U.S. accents variably appears today in eastern New England, New York City, and some of the former plantation South primarily among older speakers (and, relatedly, some African-American Vernacular English across the country), though the vowel-consonant cluster found in "bird", "work", "hurt", "learn", etc.

[106] However, a General American sound system also has some debated degree of influence nationwide, for example, gradually beginning to oust the regional accent in urban areas of the South and at least some in the Inland North.

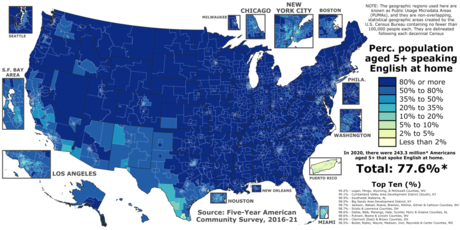

32 of the 50 states, in some cases as part of what has been called the English-only movement, have adopted legislation granting official or co-official status to English.