Indigenous languages of the Americas

The most widely reported is Joseph Greenberg's Amerind hypothesis,[1] which, however, nearly all specialists reject because of severe methodological flaws; spurious data; and a failure to distinguish cognation, contact, and coincidence.

[2] According to UNESCO, most of the Indigenous languages of the Americas are critically endangered, and many are dormant (without native speakers but with a community of heritage-language users) or entirely extinct.

[3][4] The most widely spoken Indigenous languages are Southern Quechua (spoken primarily in southern Peru and Bolivia) and Guarani (centered in Paraguay, where it shares national language status with Spanish), with perhaps six or seven million speakers apiece (including many of European descent in the case of Guarani).

In the United States, 372,000 people reported speaking an Indigenous language at home in the 2010 census.

Over a thousand known languages were spoken by various peoples in North and South America prior to their first contact with Europeans.

The European colonizing nations and their successor states had widely varying attitudes towards Native American languages.

Many Indigenous languages have become critically endangered, but others are vigorous and part of daily life for millions of people.

Examples are Quechua in Peru and Aymara in Bolivia, where in practice, Spanish is dominant in all formal contexts.

In the North American Arctic region, Greenland in 2009 elected Kalaallisut[10] as its sole official language.

The US Marine Corps recruited Navajo men, who were established as code talkers during World War II.

[11] Roger Blench (2008) has advocated the theory of multiple migrations along the Pacific coast of peoples from northeastern Asia, who already spoke diverse languages.

[citation needed] The Na-Dené, Algic, and Uto-Aztecan families are the largest in terms of number of languages.

Na-Dené and Algic have the widest geographic distributions: Algic currently spans from northeastern Canada across much of the continent down to northeastern Mexico (due to later migrations of the Kickapoo) with two outliers in California (Yurok and Wiyot); Na-Dené spans from Alaska and western Canada through Washington, Oregon, and California to the U.S. Southwest and northern Mexico (with one outlier in the Plains).

Demonstrating genetic relationships has proved difficult due to the great linguistic diversity present in North America.

[59] Another area of considerable diversity appears to have been the Southeastern Woodlands;[citation needed] however, many of these languages became extinct from European contact and as a result they are, for the most part, absent from the historical record.

Ejective consonants are also common in western North America, although they are rare elsewhere (except, again, for the Caucasus region, parts of Africa, and the Mayan family).

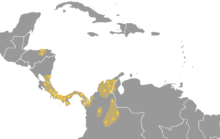

Mayan languages are spoken by at least six million Indigenous Maya, primarily in Guatemala, Mexico, Belize and Honduras.

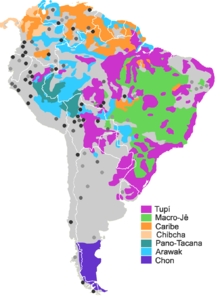

The situation of language documentation and classification into genetic families is not as advanced as in North America (which is relatively well studied in many areas).

Some proposals are viewed by specialists in a favorable light, believing that genetic relationships are very likely to be established in the future (for example, the Penutian stock).

[67] This notion was rejected by Lyle Campbell, who argued that the frequency of the n/m pattern was not statistically elevated in either area compared to the rest of the world.

If all the proposed Penutian and Hokan languages in the table below are related, then the frequency drops to 9% of North American families, statistically indistinguishable from the world average.