Ammonoidea

They are more closely related to living octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish (which comprise the clade Coleoidea) than they are to nautiluses (family Nautilidae).

[1] The earliest ammonoids appeared during the Emsian stage of the Early Devonian, with the last species vanishing during or soon after the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event.

They are often called ammonites, which is most frequently used for members of the order Ammonitida, the only remaining group of ammonoids from the Jurassic up until their extinction.

[3] Ammonoids are excellent index fossils, and they have been frequently used to link rock layers in which a particular species or genus is found to specific geologic time periods.

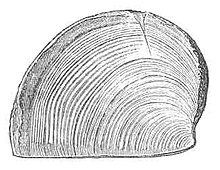

The name "ammonite", from which the scientific term is derived, was inspired by the spiral shape of their fossilized shells, which somewhat resemble tightly coiled rams' horns.

The classification of ammonoids is based in part on the ornamentation and structure of the septa comprising their shells' gas chambers.

The Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology (Part L, 1957) divides the Ammonoidea, regarded simply as an order, into eight suborders, the Anarcestina, Clymeniina, Goniatitina and Prolecanitina from the Paleozoic; the Ceratitina from the Triassic; and the Ammonitina, Lytoceratina and Phylloceratina from the Jurassic and Cretaceous.

A thin living tube called a siphuncle passed through the septa, extending from the ammonite's body into the empty shell chambers.

A primary difference between ammonites and nautiloids is the siphuncle of ammonites (excepting Clymeniina) runs along the ventral periphery of the septa and camerae (i.e., the inner surface of the outer axis of the shell), while the siphuncle of nautiloids runs more or less through the center of the septa and camerae.

The earliest ammonoids lacked a median saddle and instead had a single midline ventral lobe, which in later forms is split into two or more components.

This distinguishes them from living nautiloides (Nautilus and Allonautilus) and typical Nautilida, in which the siphuncle runs through the center of each chamber.

[7] However the very earliest nautiloids from the Late Cambrian and Ordovician typically had ventral siphuncles like ammonites, although often proportionally larger and more internally structured.

The most fundamental difference in spiral form is how strongly successive whorls expand and overlap their predecessors.

This can be inferred by the size of the umbilicus, the sunken-in inner part of the coil, exposing older and smaller whorls.

[15] In late Norian age in Triassic the first heteromorph ammonoid fossils belongs to the genus Rhabdoceras.

[16] In the Jurassic an uncoiled shell was found in the Spiroceratoidea,[17] but by the end of Cretaceous the only heteromorph ammonites remaining belonged to the suborder Ancyloceratina.

Perhaps the most extreme and bizarre-looking example of a heteromorph is Nipponites, which appears to be a tangle of irregular whorls lacking any obvious symmetric coiling.

In the past, these plates were assumed to serve in closing the opening of the shell in much the same way as an operculum, but more recently they are postulated to have been a jaw apparatus.

The modern Nautilus lacks any calcitic plate for closing its shell, and only one extinct nautiloid genus is known to have borne anything similar.

[30]A 2021 study reported specimens of the scaphitid ammonite genera Rhaeboceras and Hoploscaphites with mineralised hooks, which were likely present on the ends of a pair of enlarged tentacles.

Until new data comes to light, all life reconstructions of ammonites should be taken as extremely tentative, almost speculative renditions of their actual appearance.

However, the triangular formation of the holes, their size and shape, and their presence on both sides of the shells, corresponding to the upper and lower jaws, is more likely evidence of the bite of a medium-sized mosasaur preying upon ammonites.

[36] Few of the ammonites occurring in the lower and middle part of the Jurassic period reached a size exceeding 23 cm (9.1 in) in diameter.

Much larger forms are found in the later rocks of the upper part of the Jurassic and the lower part of the Cretaceous, such as Titanites from the Portland Stone of Jurassic of southern England, which is often 53 cm (1.74 ft) in diameter, and Parapuzosia seppenradensis of the Cretaceous period of Germany, which is one of the largest-known ammonites, sometimes reaching 2 m (6.6 ft) in diameter.

The largest-documented North American ammonite is Parapuzosia bradyi from the Cretaceous, with specimens measuring 137 cm (4.5 ft) in diameter.

Ammonoids are widely thought to have originated from straight-shelled (orthocone) "nautiloids" belong to Bactritida during the early Devonian (Emsian), with transitional fossils showing the transition from a straight shell, to a curved (cyrtoconic) shell to a relaxed (gyroconic) spiral and finally to a tight spiral.

Ammonoids rediversified during the following Famennian, which also saw the radical shift of the siphuncle from a lower (ventral) to upper (dorsal) position.

It has been suggested that ocean acidification generated by the impact played a key role in their extinction, as the larvae of ammonites were likely small and planktonic, and would have been heavily affected.

[43] Nautiloids, exemplified by modern nautiluses, are conversely thought to have had a reproductive strategy in which eggs were laid in smaller batches many times during the lifespan, and on the sea floor well away from any direct effects of such a bolide strike, and thus survived.

[30] Some reports suggest that a few ammonite species may have persisted into the very early Danian stage of the Paleocene, before going extinct.