Bivalvia

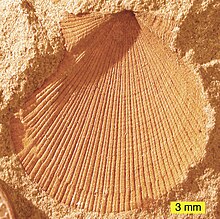

And see text Bivalvia (/baɪˈvælviə/) or bivalves, in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class of aquatic molluscs (marine and freshwater) that have laterally compressed soft bodies enclosed by a calcified exoskeleton consisting of a hinged pair of half-shells known as valves.

[38] In more advanced bivalves, water is drawn into the shell from the posterior ventral surface of the animal, passes upwards through the gills, and doubles back to be expelled just above the intake.

For example, the cilia on the gills, which originally served to remove unwanted sediment, have become adapted to capture food particles, and transport them in a steady stream of mucus to the mouth.

[42] Carnivorous bivalves generally have reduced crystalline styles and the stomach has thick, muscular walls, extensive cuticular linings and diminished sorting areas and gastric chamber sections.

Brachiopods have a lophophore, a coiled, rigid cartilaginous internal apparatus adapted for filter feeding, a feature shared with two other major groups of marine invertebrates, the bryozoans and the phoronids.

By the Early Silurian, the gills were becoming adapted for filter feeding, and during the Devonian and Carboniferous periods, siphons first appeared, which, with the newly developed muscular foot, allowed the animals to bury themselves deep in the sediment.

These included increasing relative buoyancy in soft sediments by developing spines on the shell, gaining the ability to swim, and in a few cases, adopting predatory habits.

[58] For a long time, bivalves were thought to be better adapted to aquatic life than brachiopods were, outcompeting and relegating them to minor niches in later ages.

Evidence given for this included the fact that bivalves needed less food to subsist because of their energetically efficient ligament-muscle system for opening and closing valves.

[60] The adult maximum size of living species of bivalve ranges from 0.52 mm (0.02 in) in Condylonucula maya,[61] a nut clam, to a length of 1,532 millimetres (60.3 in) in Kuphus polythalamia, an elongated, burrowing shipworm.

[62] However, the species generally regarded as the largest living bivalve is the giant clam Tridacna gigas, which can grow to a length of 1,200 mm (47 in) and a weight of more than 200 kg (441 lb).

[65] Huber states that the number of 20,000 living species, often encountered in literature, could not be verified and presents the following table to illustrate the known diversity: The bivalves are a highly successful class of invertebrates found in aquatic habitats throughout the world.

A sandy sea beach may superficially appear to be devoid of life, but often a very large number of bivalves and other invertebrates are living beneath the surface of the sand.

[67] The Antarctic scallop, Adamussium colbecki, lives under the sea ice at the other end of the globe, where the subzero temperatures mean that growth rates are very slow.

[73] Another well-travelled freshwater bivalve, the zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha) originated in southeastern Russia, and has been accidentally introduced to inland waterways in North America and Europe, where the species damages water installations and disrupts local ecosystems.

When buried in the sediment, burrowing bivalves are protected from the pounding of waves, desiccation, and overheating during low tide, and variations in salinity caused by rainwater.

Many species of demersal fish feed on them including the common carp (Cyprinus carpio), which is being used in the upper Mississippi River to try to control the invasive zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha).

[86] Shellfish have formed part of the human diet since prehistoric times, a fact evidenced by the remains of mollusc shells found in ancient middens.

Examinations of these deposits in Peru has provided a means of dating long past El Niño events because of the disruption these caused to bivalve shell growth.

The animal can regenerate them later, a process that starts when the cells close to the damaged site become activated and remodel the tissue back to its pre-existing form and size.

[97] Oysters, mussels, clams, scallops and other bivalve species are grown with food materials that occur naturally in their culture environment in the sea and lagoons.

Culture there takes place on the bottom, in plastic trays, in mesh bags, on rafts or on long lines, either in shallow water or in the intertidal zone.

[102] Bivalves have been an important source of food for humans at least since Roman times[103] and empty shells found in middens at archaeological sites are evidence of earlier consumption.

[105] Paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP) is primarily caused by the consumption of bivalves that have accumulated toxins by feeding on toxic dinoflagellates, single-celled protists found naturally in the sea and inland waters.

[113] A study of nine different bivalves with widespread distributions in tropical marine waters concluded that the mussel, Trichomya hirsuta, most nearly reflected in its tissues the level of heavy metals (Pb, Cd, Cu, Zn, Co, Ni, and Ag) in its environment.

The import and export of goods made with nacre are controlled in many countries under the International Convention of Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

[128] Roman myth has it that Venus, the goddess of love, was born in the sea and emerged accompanied by fish and dolphins, with Botticelli depicting her as arriving in a scallop shell.

Since the year 2000, taxonomic studies using cladistical analyses of multiple organ systems, shell morphology (including fossil species) and modern molecular phylogenetics have resulted in the drawing up of what experts believe is a more accurate phylogeny of the Bivalvia.

Subclasses and orders given are: Prionodesmacea have a prismatic and nacreous shell structure, separated mantle lobes, poorly developed siphons, and hinge teeth that are lacking or unspecialized.

Teleodesmacea on the other hand have a porcelanous and partly nacreous shell structure; Mantle lobes that are generally connected, well developed siphons, and specialized hinge teeth.

( Tridacna gigas )

( Ensis ensis )

- posterior adductor

- anterior adductor

- outer left gill demibranch

- inner left gill demibranch

- excurrent siphon

- incurrent siphon

- foot

- teeth

- hinge

- mantle

- umbo

- sagittal plane

- growth lines

- ligament

- umbo