Amplitude modulation

It was developed during the first quarter of the 20th century beginning with Roberto Landell de Moura and Reginald Fessenden's radiotelephone experiments in 1900.

[1] This original form of AM is sometimes called double-sideband amplitude modulation (DSBAM), because the standard method produces sidebands on either side of the carrier frequency.

For example, in AM radio communication, a continuous wave radio-frequency signal has its amplitude modulated by an audio waveform before transmission.

A disadvantage of all amplitude modulation techniques, not only standard AM, is that the receiver amplifies and detects noise and electromagnetic interference in equal proportion to the signal.

This is in contrast to frequency modulation (FM) and digital radio where the effect of such noise following demodulation is strongly reduced so long as the received signal is well above the threshold for reception.

This does not work for single-sideband suppressed-carrier transmission (SSB-SC), leading to the characteristic "Donald Duck" sound from such receivers when slightly detuned.

A more complex form of AM, quadrature amplitude modulation is now more commonly used with digital data, while making more efficient use of the available bandwidth.

A simple form of amplitude modulation is the transmission of speech signals from a traditional analog telephone set using a common battery local loop.

The result is a varying amplitude direct current, whose AC-component is the speech signal extracted at the central office for transmission to another subscriber.

In the receiver, the automatic gain control (AGC) responds to the carrier so that the reproduced audio level stays in a fixed proportion to the original modulation.

This typically involves a so-called fast attack, slow decay circuit which holds the AGC level for a second or more following such peaks, in between syllables or short pauses in the program.

[4] However, the practical development of this technology is identified with the period between 1900 and 1920 of radiotelephone transmission, that is, the effort to send audio signals by radio waves.

The first AM transmission was made by Canadian-born American researcher Reginald Fessenden[5] on December 23, 1900[6] using a spark gap transmitter with a specially designed high frequency 10 kHz interrupter,[7] over a distance of one mile (1.6 km) at Cobb Island, Maryland, US.

This was a radical idea at the time, because experts believed the impulsive spark was necessary to produce radio frequency waves, and Fessenden was ridiculed.

He invented and helped develop one of the first continuous wave transmitters – the Alexanderson alternator, with which he made what is considered the first AM public entertainment broadcast on Christmas Eve, 1906.

Early experiments in AM radio transmission, conducted by Fessenden, Valdemar Poulsen, Ernst Ruhmer, Quirino Majorana, Charles Herrold, and Lee de Forest, were hampered by the lack of a technology for amplification.

The vacuum tube feedback oscillator, invented in 1912 by Edwin Armstrong and Alexander Meissner, was a cheap source of continuous waves and could be easily modulated to make an AM transmitter.

[4] His analysis also showed that only one sideband was necessary to transmit the audio signal, and Carson patented single-sideband modulation (SSB) on 1 December 1915.

[4] This advanced variant of amplitude modulation was adopted by AT&T for longwave transatlantic telephone service beginning 7 January 1927.

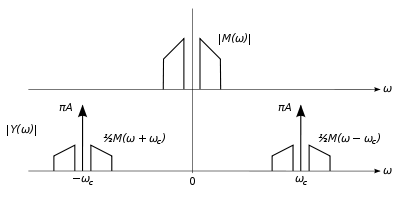

The modulation m(t) may be considered to consist of an equal mix of positive and negative frequency components, as shown in the top of figure 2.

Although the bandwidth of an AM signal is narrower than one using frequency modulation (FM), it is twice as wide as single-sideband techniques; it thus may be viewed as spectrally inefficient.

For this reason analog television employs a variant of single-sideband (known as vestigial sideband, somewhat of a compromise in terms of bandwidth) in order to reduce the required channel spacing.

Even (analog) television, with a (largely) suppressed lower sideband, includes sufficient carrier power for use of envelope detection.

But for communications systems where both transmitters and receivers can be optimized, suppression of both one sideband and the carrier represent a net advantage and are frequently employed.

This cannot be produced using the efficient high-level (output stage) modulation techniques (see below) which are widely used especially in high power broadcast transmitters.

Thus double-sideband transmission is generally not referred to as "AM" even though it generates an identical RF waveform as standard AM as long as the modulation index is below 100%.

With DSP many types of AM are possible with software control (including DSB with carrier, SSB suppressed-carrier and independent sideband, or ISB).

High-power AM transmitters (such as those used for AM broadcasting) are based on high-efficiency class-D and class-E power amplifier stages, modulated by varying the supply voltage.

[11] Older designs (for broadcast and amateur radio) also generate AM by controlling the gain of the transmitter's final amplifier (generally class-C, for efficiency).

The following types are for vacuum tube transmitters (but similar options are available with transistors):[12][13] The simplest form of AM demodulator consists of a diode which is configured to act as envelope detector.