Anarchism in Belgium

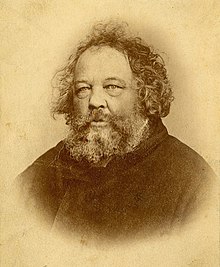

In September 1872, during the Hague Congress of the International Workingmen's Association, the Belgian delegates spoke out against the exclusion of Mikhail Bakunin proposed by the General Council of London, dominated by Karl Marx.

Like Bakunin, the Belgian delegates refused to achieve their objectives by conquering political power and were in favor of a federalist structure of the International, in which the local groups retained a large degree of autonomy.

But the announced revolution was long overdue and the social-democratic tendency, particularly present in Ghent and Brussels, gradually won out over the anti-political revolutionary.

[4] The Walloon uprising of 1886 designated a series of insurrectional workers' strikes that began on 18 March with a commemoration of the 15th anniversary of the Paris Commune, organized by the Revolutionary Anarchist Group of Liège.

In 1902, Georges Thonar chaired the "revolutionary congress" of Liège which was a success of participation but gave few concrete results, in particular because of individualism and the fear of any authoritarianism which paralyzed any beginnings of organization.

[8] For him, anarchism was located in "an active propaganda, purely theoretical and without phrases", aiming at "integral education" through study circles, schools, conferences, newspapers and brochures.

"[9] In October 1904 in Charleroi and on this basis, Thonar, assisted by Émile Chapelier, brought together a libertarian communist congress of around a hundred fairly representative militants who unanimously adopted his text and laid the foundations for a Friendly Federation of Anarchists.

The organization project, entirely developed by Georges Thonar, in a way leader of the movement at the time, speaks of a libertarian federalism based on voluntary collaboration: each group and each individual retains its autonomy, and no one imposes decisions (which makes it possible to overcome the reluctance of those who fear the appearance of a certain authoritarianism).

[11] The project was the implementation of libertarian communism: common property, communal work (gardening and poultry farming essentially) and consumption according to the principle of "From each according to their ability, to each according to their needs".

The colony published multiple brochures, which helped reactivate Belgian and international anarchism, on revolutionary syndicalism, neomalthusianism, Esperanto, free love, etc.

[22][1] Following the model of the French CGT, for the new Confederation, it was a question of bringing together all the trades in a single agreement so as to create an anti-political union capable of carrying out the revolutionary general strike.

[23] Founded by Léopold Preumont, from June 1907, Henri Fuss succeeded him at the head of the newspaper which was both a propaganda tool and a rallying center for the unions of Charleroi and Liège, which claim to be in direct action.

[8] The Belgian CGT grew in the following years but its newspaper, L’Action Directe and some of its members were prosecuted on several occasions, in particular because of their anti-militarist positions or their participation in strikes.

It contained two epigrams: "Patriotism is the last refuge of a rascal" by August Spies and "Our enemy is our master" by Jean de La Fontaine, and followed the newspaper L'Antipatriote.

[33] "Le Flambeau is not a journal of theory, nor a gossip sheet, it is a revolutionary combat organ, the cry of the oppressed, the expression of a feeling of revolt.

This resolutely libertarian approach led them to adopt a rather nuanced point of view with regard to the debate on the role of the State, a conflict which is at the basis of the split of the First International.

The group organized more than a hundred conferences on fields as diverse as sociology, politics, economics, psychology, literature, philosophy, sciences, Fine Arts, etc.

[70] The group publishes an eponymous monthly review which should serve as "a link between all those who, beyond the fray of today and tomorrow, are looking for the possible bases of a free evolution of men in societies".

[71] It therefore declared itself open to all, as attested by the formula written on the back cover of each issue of the review: "Pensée et Action intends to seek, beyond any sectarianism, any political or dogmatic ideology, the elements of a genuinely revolutionary culture, defending the merits of the essential demands of the mind and of men!

The group was quickly undermined by divisions between individualists, including Hem Day and Joseph de Smet, and the libertarian communist fringe.

For example, at the wedding of Baudouin, the young Belgian king, with Fabiola, from the Spanish nobility, the association denounced the living conditions under the Franco dictatorship and the passive collaboration of the royal family and clerical circles.

[73] In 1958, young people, including Stéphane Huvenne,[74] joined the association and offered to organize more spectacular or even violent actions, which caused tensions between the new and the old generation mainly made up of non-violent activists.

The young Spanish anti-fascists decided to leave SIA and to join the Libertarian Youth (FIJL), then in exile on Belgian territory since its ban in France on 9 August 1963.

[85] In Liège, in the wake of the events of May 68 and the student movement Boule de neige, the anarchist monthly "Le Libertaire" was published, in which Noël Godin, Edgard Morin, JP Delriviere, Mihaili Djosson and Yves Thelen participated.

The group "Socialism and Freedom" was influenced by "Noir & Rouge", which proclaimed itself anarchist-communist and many texts, in the review, alluded to contributions of dialectical materialism.

Concretely, the group's mission was to provide the most precise and complete documentation possible to activists, supporters, students or researchers wishing to learn about the anarchist movement, its press, its literature and its actions.

Finally, the association supported free education centers or community houses.A Hem Day Fund committee was also created to manage the documents offered by the anarchist.

[87] For the duration of its publication (30 years and 282 issues), its openness to debates and its posters contributed to broadening the audience of libertarian ideas in French-speaking Belgium.

Its goal was not to address convinced activists but to reach out to the periphery of the movement, that is to say the supporters who hesitate to get involved or who by their ideas are interested in libertarian or anti-authoritarian practices.

The organisation is structured in thematic fronts of struggle (trade union, feminist, antifascist, queer, social ecology) which aim to coordinate and implement the political line decided by the collective.