Anarchism in Ukraine

Philosophical anarchism first emerged from the radical movement during the Ukrainian national revival, finding a literary expression in the works of Mykhailo Drahomanov, who was himself inspired by the libertarian socialism of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon.

The ideas of anarcho-communism, anarcho-syndicalism and individualist anarchism all took root in Ukrainian revolutionary circles, with syndicalism itself developing a notably strong hold in Odesa, while acts of anarchist terrorism by cells such as the Black Banner became more commonplace.

[2] By this time, the Cossacks had emerged from the conflict, establishing themselves along the banks of the Don and Dniepr rivers, where they practiced a form of participatory democracy in popular assemblies (Krugs) and elected their own military leaders (Atamans).

[5] The Zaporozhian Sich was itself organized along democratic and egalitarian lines, where military and civilian officials were all directly elected for one-year terms and subject to instant recall by the assemblies, while its land was distributed equally among the people.

Viewing national liberation as "inseparable from social emancipation", he instead encouraged for the Hromada to concentrate on building a bottom-up form of democracy of small communities organized on a federative basis.

[13] In 1874, the Narodniks' "Going to the People" campaign culminated in a number of Ukrainian revolutionary anarchists (buntars), led by Yakov Stefanovich, organizing a peasant revolt in Chyhyryn, before being suppressed by Russian authorities.

In 1895, members of the URP were elected to the Galician Diet and the Austrian parliament, by which point its party congresses were beginning to call for Ukrainian independence and endorsed a number of strikes by agricultural workers.

[18] The living conditions of Pale nourished the growth of the Ukrainian anarchist movement, which grew particularly strong in Jewish towns, where workers' circles began to educate themselves on a number of radical ideas.

[20] Popular discontent with the Tsarist autocracy eventually culminated in the 1905 Revolution, during which much of the country rebelled against the Russian Empire, with a general strike in October successfully securing civil liberties and the constitution of the State Duma.

[26] In Katerynoslav, Odesa and Sevastopol, the Black banner organized a number of detachments that carried out bombings on buildings, murdered and robbed rich people, and fought with the police in the streets.

Always, wherever he may be, he will be overtaken by an anarchist's bomb or bullet.Although the terrorists within the Black Banner had been energised by their attacks in Odesa, a dissenting Communard group had also emerged that called for the organization of a mass uprising, rather than individual acts of propaganda of the deed.

"[39] The anti-intellectualism of the Polish revolutionary Jan Wacław Machajski, inspired by Bakunin's insurrectionary anarchism,[40] also made an impression among Ukrainian anarchists, with the Black Banner members Olha Taratuta and Vladimir Striga organizing alongside Makhaevists in a secret society known as the Intransigents.

[41] Even the Odesa Anarcho-Syndicalists were influenced by Machajski's anti-intellectualism, with their denunciations of social democracy being rooted in their opposition to the creation of a new intellectual elite, declaring that "the liberation of the workers must be the task of the working class itself".

[43] Pyotr Stolypin instituted pacification measures against the terrorist movement, placing the Russian Empire under a state of emergency and unleashing a wave of punishment against the Black Banner and other radical organisations, with a number of militants committing suicide after their capture.

[53] Makhno subsequently returned to Ukraine, where he began organizing an agricultural workers' union and was later elected chairman of the Huliaipole Soviet, from which he ordered the armed expropriation of land by the peasantry.

By August 1917, Makhno had been elected as the Chairman of the local Soviet, a position from which he organized an armed peasant band to expropriate the large privately held estates and redistribute those lands equally to the whole peasantry.

[77] Here he met with Peter Kropotkin and held an interview with Vladimir Lenin, during which he debated the differences between authoritarian and libertarian communism, eventually enlisting Bolshevik support for the anarchists that were holding back the counterrevolutionary advance in Ukraine.

[78] Alienated by the "paper revolution" of the Bolsheviks in Moscow, in July 1918 Makhno returned to Huliapole, where he found the village occupied by both the Austro-Hungarian Army and the Ukrainian troops of Hetman Pavlo Skoropadskyi.

When famine threatened Petrograd and Moscow, Huliaipole's Ukrainian peasants exported large amounts of grain to the Russian cities, while Makhno himself was cast as a "courageous partisan" by the Soviet press.

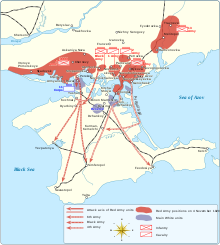

But in September 1919, the Makhnovists returned and launched a surprise counterattack in Uman, cutting Denikin's army off from its supply lines, which forced him to call off the Moscow offensive and retreat to Crimea.

[94] The Makhnovists emphasised self-organization and self-determination, agitating against political party activists that called for centralisation and advising unpaid workers to seize control of their workplaces and charge the customers directly.

[98] But in October 1920, Pyotr Wrangel launched an offensive from Crimea, causing the Makhnovists to once again sign a truce with the Bolsheviks, on the conditions of their autonomy, the amnesty of all anarchist political prisoners and the right to freedom of speech.

Following Wrangel's evacuation of the Crimea, the Makhnovist commanders were immediately shot by the Bolsheviks, Huliaipole was subsequently attacked by the Red Army and members of anarchist organizations throughout Ukraine were arrested by the Cheka.

[101] The power vacuum in Ukraine was definitively filled with the establishment of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, with the Red Army taking control of the Dnieper River basin by the end of 1921.

[113] With the Bolsheviks' attention turned to its ongoing internal conflict between Stalinism and Trotskyism, anarchists declared their neutrality in the dispute, while expressing some sympathy for the Group of Democratic Centralism, which had numerous members in Ukraine.

[116] There was also an upsurge in violent activity, with anarchists being reported to have gassed a theatre pit in Kharkiv, agitated against taxation in rural Ukrainian villages and attempted to carry out expropriations in Poltava.

[125] Soviet authorities were troubled by the growth of the anarchist underground and the leading role of anarcho-syndicalists in the workers' movement, as a number of "free trade unions" had organized strike actions, including among the miners in Bakhmut.

[134] Drahomanov studies also underwent censorship during the Era of Stagnation but resurfaced once again during the 1980s, when students began to develop his theory into an alternative form of socialism to the prevailing Marxism-Leninism, growing substantially in scale.

[136] But the Ukrainian new left that had first constituted itself during the period of Perestroika, forming in opposition to the dominant Communist Party of Ukraine, largely failed to construct a sustainable nationwide political movement.

[158] In the wake of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Ukrainian anarchists were among those that joined the Territorial Defense Forces, with a group calling itself the Resistance Committee establishing an anti-authoritarian "international detachment" in Kyiv.