Classical Chinese poetry

Generally, folk-type poems are anonymous, and many show signs of having been edited or polished in the process of recording them in written characters.

Jian'an is considered as a separate period because this is one case where the poetic developments fail to correspond with the neat categories aligned to chronology by dynasty.

The Six Dynasties (220–589) also witnessed major developments in Classical Chinese poetry, especially emphasizing romantic love, gender roles, and human relationships, and including the important collection New Songs from the Jade Terrace.

The Three Kingdoms period was a violent one, a characteristic sometimes reflected in the poetry or highlighted by the poets' seeking refuge from the social and political turmoil by retreating into more natural settings, as in the case of the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove.

The Jin dynasty era was typified poetically by, for example, the Orchid Pavilion Gathering of 42 literati; the romantic Midnight Songs poetry; and, Tao Yuanming, the great and highly personal poet who was noted for speaking in his own voice rather than a persona.

Some of the highlights of the poetry of the Northern and Southern Dynasties include the Yongming poets, the anthology collection New Songs from the Jade Terrace, and Su Hui's Star Gauge.

Their popularity in the historical Chinese cultural area has varied over time, with certain authors coming in and out of favor and others permanently obscure.

In part because of the prevalence of rhymed and parallel structures within Tang poetry, it also has a role in linguistics studies, such as in the reconstruction of Middle Chinese pronunciation.

The most prominent ci-poets include Su Shi (Dongpo), Xin Qiji, Li Qingzhao, Liu Yong and Zhou Bangyan.

Prominent Song shi-poets include Su Shi (Dongpo), Huang Tingjian, Ouyang Xiu, Lu You and Yang Wanli.

According to the Japanese scholar Yoshikawa Kōjirō, Yuan Haowen "may well be the foremost Chinese poet from Du Fu to the present" (John Timothy Wixted's translation).

Yuan drama's notable qu form was set to music, restricting each individual poem to one of nine modal key selections and one of over two hundred tune patterns.

[9] Depending on the pattern, this imposed fixed rhythmic and tonal requirements that remained in place for future poets even if its musical component was later lost.

Noteworthy Yuan qu-poets include Bai Pu, Guan Hanqing, Ma Zhiyuan, Zheng Guangzu and Qiao Ji.

[10] One exponent of the popular West Lake landscape poetry that flourished at this time was the always skilful and elegant, if sometimes too facile, poet Zhang Kejiu.

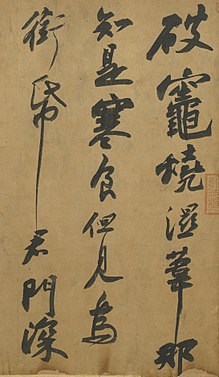

A painter-poet tradition also thrived during the Yuan period, including masterful calligraphy done by, for example, Ni Zan and Wu Zhen.

[11] Another exemplar was Zhao Mengfu (1254–1322), a former official of the Song dynasty who served under the Mongol administration of the Yuan and whose wife Guan Daosheng (1262–1319) was also a painter-poet and calligrapher.

Thanks to educational opportunities made possible by commercial printing and the reinvigorated examination system, a massively larger literate population emerged.

With over one million surviving Ming poems, modern critics and researchers have been unable to definitively answer whether that conviction is a prejudice or a fact.

Li Yu is also a prime example of the Ming-Qing transition's emotional outpouring when disorder swept away Ming stability as the incoming dynasty's Manchu warriors conquered from North to South.

The fresh poetic voice of Yuan Mei has won wide appeal, as have the long narrative poems by Wu Jiaji.

[18] The challenge for modern researchers grew as even more people became poets and even more poems were preserved, including (with Yuan Mei's encouragement) more poetry by women.

[citation needed] However, the development and great expansion of modern Chinese poetry is generally thought to start at this point in history, or shortly afterwards.

As is the case with many ancient writing systems, such as the Phoenician alphabet, many of the earliest characters likely began as pictograms, with a given word corresponding to a picture representing that idea.

The resulting strong graphical aspect, versus a weaker phonetic element (in comparison to other languages, such as English) is very important.

Poems in China, as elsewhere, are firstly patterns of sound...."[25] However, Graham is in no way suggesting that the Chinese poet is unaware of the background considerations stemming from character construction.

Often these persona types were quite conventional, such as the lonely wife left behind at home, the junior concubine ignored and sequestered in the imperial harem, or the soldier sent off to fight and die beyond the remote frontier.

One example of this is the poetry written to accompany of to follow the eight-fold settings of the Eight Views of Xiaoxiang which were popularized during the Song dynasty; although, the theme can certainly be traced back as far as the Chuci.

Examples include occasions of parting from a close friend for an extended period of time, expression of gratitude for a gift or act of someone, lamentations about current events, or even as a sort of game at social gatherings.

A more recent global influence has developed in modern times, including Beat poetry, exponents of which even produced translations of Classical Chinese poetry into English, such as Kenneth Rexroth (One Hundred Poems From the Chinese, 1956) and Gary Snyder (Riprap and Cold Mountain Poems, 1959, which includes translations of Hanshan).