Su Shi

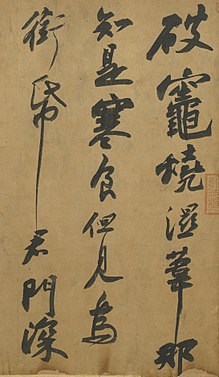

[5] Su is widely regarded as one of the most accomplished figures in classical Chinese literature,[4] leaving behind him a prolific collection of poems, lyrics, prose, and essays.

His poetry had enduring popularity and influence in China and other areas in the near vicinity such as Japan, and is well known in some English-speaking countries through translations by Arthur Waley and Stephen Owen, among others.

When he reached the age of 10, his education transitioned to homeschooling, initially guided by his mother, Lady Cheng, and subsequently by his father, Su Xun.

Over the course of more than a decade, Su Xun dedicated himself to comprehensive studies of classical literature, philosophy, and historical texts, while providing coaching to his two adolescent sons as they prepared for the imperial examination.

[11] In 1057, at the age of 19, Su Shi and his brother both passed the highest-level civil service examinations and attained the degree of jinshi, a prerequisite for high government office.

[12] His accomplishments at such a young age attracted the attention of Emperor Renzong and leading literary figure Ouyang Xiu, who became Su's patron thereafter.

When the 1057 jinshi examinations were given, Ouyang Xiu unexpectedly required candidates to write in the ancient prose style when answering questions on the Confucian classics.

Su Shi once wrote a poem criticizing Wang Anshi's reforms, especially the government monopoly imposed on the salt industry.

[16] The dominance of the reformist faction at court allowed the New Policy Group greater ability to have Su Shi exiled for political crimes.

Although political bickering and opposition usually split ministers of court into rivaling groups, there were moments of non-partisanship and cooperation from both sides.

[19] After his death he gained even greater popularity, as people sought to collect his calligraphy, depicted him in paintings, marked his visit to numerous places with stone inscriptions and built shrines in his honor.

Heartbroken, Su Shi wrote a memorial (亡妻王氏墓志銘), stating that Wang had not just been a virtuous wife, but had also frequently advised him regarding the integrity of his acquaintances during his time as an official.

Su expressed his gratitude to Zhaoyun for her companionship to his exile in his old age, as well as her shared quest with the poet for immortal life via Buddhist and Taoist practice.

[24] Su's friend, fellow poet Qin Guan wrote a poem, "A Gift for Dongpo's concubine Zhaoyun" (贈東坡妾朝雲), praising her beauty and lovely voice.

Zhaoyun remained a faithful companion to Su Shi after Runzhi's death, and died of illness on 13 August 1095 (紹聖三年七月五日) at Huizhou.

"[11] As evening clouds withdraw a clear cool air floods in the jade wheel passes silently across the Silver River this life this night has rarely been kind

While a significant portion of his poetry is in the shi format, it is his 350 ci style poems that largely cemented his poetic legacy.

In both his literary creations and visual artistry, Su Shi seamlessly blended elements of spontaneity, objectivity with detailed and vivid depictions of the natural world.

Su Shi is renowned as a founding figure of the háofàng school in ci poetry, characterized by a spirit of boldness and a broader theme.

Su Shi expanded the ci genre's thematic range, infusing it with a variety of non-traditional topics, many of which were drawn from his own life experiences.

His lyrics delved into deeper, more contemplative subjects like aging, mortality, and the intricacies of public service, resonating more profoundly with contemporary audiences.

As an innovator of the háofàng style, he introduced elements typically associated with masculine activities, including hunting motifs, and intertwined Buddhist philosophical concepts and political references, traditionally reserved for more esteemed forms of poetry.

[27] Some of his notable poetry works include the First and Second Chibifu (赤壁賦 The Red Cliffs, written during his first exile), Nian Nu Jiao: Chibi Huai Gu (念奴嬌·赤壁懷古 Remembering Chibi, to the tune of Nian Nu Jiao) and Shui diao ge tou (水調歌頭 Remembering Su Zhe on the Mid-Autumn Festival, 中秋節).

料峭春風吹酒醒, 微冷, 山頭斜照卻相迎。 回首向來蕭瑟處, 歸去, 也無風雨也無晴。 Pay no heed to those sounds, piercing the woods, hitting leaves-- why should it stop me from whistling or chanting and walking slowly along?

[31] Su Shi also wrote of his travel experiences in 'daytrip essays',[32] which belonged in part to the popular Song era literary category of 'travel record literature' (youji wenxue) that employed the use of narrative, diary, and prose styles of writing.

[33] Although other works in Chinese travel literature contained a wealth of cultural, geographical, topographical, and technical information, the central purpose of the daytrip essay was to use a setting and event in order to convey a philosophical or moral argument, which often employed persuasive writing.

[34] While acting as Governor of Xuzhou in 1078, Su wrote a memorial to the imperial court about issues faced in the Liguo Industrial Prefecture was under his administration.

[38] Shen also wrote in his Dream Pool Essays of the year 1088 that, if properly used, sluice gates positioned along irrigation canals were most effective in depositing silt for fertilization.

Su, to explain his vegetarian inclinations, said that he never had been comfortable with killing animals for his dinner table, but had a craving for certain foods, such as clams, so he could not desist.