Ancient Greek religion

[3] Most ancient Greeks recognized the twelve major Olympian gods and goddesses—Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Demeter, Athena, Ares, Aphrodite, Apollo, Artemis, Hephaestus, Hermes, and either Hestia or Dionysus—although philosophies such as Stoicism and some forms of Platonism used language that seems to assume a single transcendent deity.

For instance, Zeus was the sky-god, sending thunder and lightning, Poseidon ruled over the sea and earthquakes, Hades projected his remarkable power throughout the realms of death and the Underworld, and Helios controlled the sun.

A few Greeks, like Achilles, Alcmene, Amphiaraus, Ganymede, Ino, Melicertes, Menelaus, Peleus, and a great number of those who fought in the Trojan and Theban wars, were considered to have been physically immortalized and brought to live forever in either Elysium, the Islands of the Blessed, heaven, the ocean, or beneath the ground.

Myths often revolved around heroes and their actions, such as Heracles and his twelve labors, Odysseus and his voyage home, Jason and the quest for the Golden Fleece and Theseus and the Minotaur.

Some creatures in Greek mythology were monstrous, such as the one-eyed giant Cyclopes, the sea beast Scylla, whirlpool Charybdis, Gorgons, and the half-man, half-bull Minotaur.

The Greeks and Romans were literate societies, and much mythology, although initially shared orally, was written down in the forms of epic poetry (such as the Iliad, the Odyssey and the Argonautica) and plays (such as Euripides' The Bacchae and Aristophanes' The Frogs).

In this field, of particular importance are certain texts referring to Orphic cults: multiple copies, ranging from between 450 BCE and 250 CE, have been found in various parts of the Greek world.

Other texts were specially composed for religious events, and some have survived within the lyric tradition; although they had a cult function, they were bound to performance and never developed into a common, standard prayer form comparable to the Christian Pater Noster.

To a large extent, in the absence of "scriptural" sacred texts, religious practices derived their authority from tradition, and "every omission or deviation arouses deep anxiety and calls forth sanctions".

[15] The animals used were, in order of preference, bulls or oxen, cows, sheep (the most common sacrifice), goats, pigs (with piglets being the cheapest mammal), and poultry (but rarely other birds or fish).

[17] For a smaller and simpler offering, a grain of incense could be thrown on the sacred fire,[18] and outside the cities farmers made simple sacrificial gifts of plant produce as the "first fruits" were harvested.

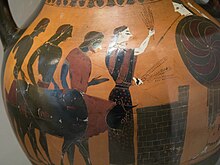

The occasions of sacrifice in Homer's epic poems may shed some light onto the view of gods as members of society, rather than external entities, indicating social ties.

More typical festivals featured a procession, large sacrifices and a feast to eat the offerings, and many included entertainments and customs such as visiting friends, wearing fancy dress and unusual behavior in the streets, sometimes risky for bystanders in various ways.

The tenemos might include many subsidiary buildings, sacred groves or springs, animals dedicated to the deity, and sometimes people who had taken sanctuary from the law, which some temples offered, for example to runaway slaves.

A typical early sanctuary seems to have consisted of a tenemos, often around a sacred grove, cave, rock (baetyl) or spring, and perhaps defined only by marker stones at intervals, with an altar for offerings.

As the centuries passed both the inside of popular temples and the area surrounding them accumulated statues and small shrines or other buildings as gifts, and military trophies, paintings and items in precious metals, effectively turning them into a type of museum.

In early days these were in wood, marble or terracotta, or in the specially prestigious form of a chryselephantine statue using ivory plaques for the visible parts of the body and gold for the clothes, around a wooden framework.

Many of the Greek statues well known from Roman marble copies were originally temple cult images, which in some cases, such as the Apollo Barberini, can be credibly identified.

It used to be thought that access to the cella of a Greek temple was limited to the priests, and it was entered only rarely by other visitors, except perhaps during important festivals or other special occasions.

[26] It was typically necessary to make a sacrifice or gift, and some temples restricted access either to certain days of the year, or by class, race, gender (with either men or women forbidden), or even more tightly.

Robert G. Boling argues that Greek and Ugaritic/Canaanite mythology share many parallel relationships and that historical trends in Canaanite religion can help date works such as Homer's Iliad and Odyssey.

Serapis was essentially a Hellenistic creation, if not devised then spread in Egypt for political reasons by Ptolemy I Soter as a hybrid of Greek and local styles of deity.

Various philosophical movements, including the Orphics and Pythagoreans, began to question the ethics of animal sacrifice, and whether the gods really appreciated it; from the surviving texts Empedocles and Theophrastus (both vegetarians) were notable critics.

The Greek gods were equated with the ancient Roman deities; Zeus with Jupiter, Hera with Juno, Poseidon with Neptune, Aphrodite with Venus, Ares with Mars, Artemis with Diana, Athena with Minerva, Hermes with Mercury, Hephaestus with Vulcan, Hestia with Vesta, Demeter with Ceres, Hades with Pluto, Tyche with Fortuna, and Pan with Faunus.

The initial decline of Greco-Roman polytheism was due in part to its syncretic nature, assimilating beliefs and practices from a variety of foreign religious traditions as the Roman Empire expanded.

[41][page needed] The Roman Emperor Julian, a nephew of Constantine, initiated an effort to end the ascension of Christianity within the empire and reorganize a syncretic version of Greco-Roman polytheism that he termed "Hellenism".

[42] Julian's Christian training influenced his decision to create a single organized version of the various old pagan traditions, with a centralized priesthood and a coherent body of doctrine, ritual, and liturgy based on Neoplatonism.

[47] Theodosius strictly enforced anti-pagan laws, had priesthoods disbanded, temples destroyed, and actively participated in Christian actions against pagan holy sites.

In 382 CE, Gratian appropriated the income and property of the remaining orders of pagan priests, disbanded the Vestal Virgins, removed altars, and confiscated temples.

[41] Greek religion and philosophy have experienced a number of revivals, firstly in the arts, humanities and spirituality of Renaissance Neoplatonism, which many believed had effects in the real world.