Lydia

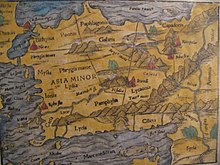

Lydia (Ancient Greek: Λυδία, romanized: Ludía; Latin: Lȳdia) was an Iron Age kingdom situated in the west of Asia Minor, in modern-day Turkey.

[1][2] Lydia is generally located east of ancient Ionia in the modern western Turkish provinces of Uşak, Manisa and inland Izmir.

Later, the military power of Alyattes and Croesus expanded Lydia, which, with its capital at Sardis, controlled all Asia Minor west of the River Halys, except Lycia.

After the Persian conquest the River Maeander was regarded as its southern boundary, and during imperial Roman times Lydia comprised the country between Mysia and Caria on the one side and Phrygia and the Aegean Sea on the other.

[8] Like the other Arzawa Lands, these kingdoms had tumultuous relations with the Hittite Empire, acting both as allies, enemies, and vassals at various points in time.

Heracles had an affair with one of Iardanus' slave-girls and their son Alcaeus was the first of the Heraclid Dynasty said to have ruled Lydia for 22 generations starting with Agron.

[16] Gyges took advantage of the power vacuum created by the Cimmerian invasions to consolidate his kingdom and make it a military power, he contacted the Neo-Assyrian court by sending diplomats to Nineveh to seek help against the Cimmerian invasions,[17] and he attacked the Ionian Greek cities of Miletus, Smyrna, and Colophon.

[22] Amidst extreme turmoil, Sadyattes was succeeded in 635 BC by his son Alyattes, who would transform Lydia into a powerful empire.

[25][22] Soon after Alyattes's ascension and early during his reign, with Assyrian approval[26] and in alliance with the Lydians,[27] the Scythians under their king Madyes entered Anatolia, expelled the Treres from Asia Minor, and defeated the Cimmerians so that they no longer constituted a threat again, following which the Scythians extended their domination to Central Anatolia[28] until they were themselves expelled by the Medes from Western Asia in the 590s BC.

[31] Alyattes continued his expansionist policy in the east, and of all the peoples to the west of the Halys River whom Herodotus claimed Alyattes's successor Croesus ruled over - the Lydians, Phrygians, Mysians, Mariandyni, Chalybes, Paphlagonians, Thyni and Bithyni Thracians, Carians, Ionians, Dorians, Aeolians, and Pamphylians - it is very likely that a number of these populations had already been conquered under Alyattes, and it is not impossible that the Lydians might have subjected Lycia, given that the Lycian coast would have been important for the Lydians because it was close to a trade route connecting the Aegean region, the Levant, and Cyprus.

[37] Croesus brought Caria under the direct control of the Lydian Empire,[21] and he subjugated all of mainland Ionia, Aeolis, and Doris, but he abandoned his plans of annexing the Greek city-states on the islands of the Aegean Sea and he instead concluded treaties of friendship with them, which might have helped him participate in the lucrative trade the Aegean Greeks carried out with Egypt at Naucratis.

[31] Although the dates for the battles of Pteria and Thymbra and of end of the Lydian empire have been traditionally fixed to 547 BC,[40] more recent estimates suggest that Herodotus's account being unreliable chronologically concerning the fall of Lydia means that there are currently no ways of dating the end of the Lydian kingdom; theoretically, it may even have taken place after the fall of Babylon in 539 BC.

[40][41] In 547 BC, the Lydian king Croesus besieged and captured the Persian city of Pteria in Cappadocia and enslaved its inhabitants.

Under the tetrarchy reform of Emperor Diocletian in 296 AD, Lydia was revived as the name of a separate Roman province, much smaller than the former satrapy, with its capital at Sardis.

Together with the provinces of Caria, Hellespontus, Lycia, Pamphylia, Phrygia prima and Phrygia secunda, Pisidia (all in modern Turkey) and the Insulae (Ionian islands, mostly in modern Greece), it formed the diocese (under a vicarius) of Asiana, which was part of the praetorian prefecture of Oriens, together with the dioceses Pontiana (most of the rest of Asia Minor), Oriens proper (mainly Syria), Aegyptus (Egypt) and Thraciae (on the Balkans, roughly Bulgaria).

Although the Seljuk Turks conquered most of the rest of Anatolia, forming the Sultanate of Ikonion (Konya), Lydia remained part of the Byzantine Empire.

While the Venetians occupied Constantinople and Greece as a result of the Fourth Crusade, Lydia continued as a part of the Eastern Roman rump state called the Nicene Empire based at Nicaea until 1261.

[44] Despite this ambiguity, this statement of Herodotus is one of the pieces of evidence most often cited on behalf of the argument that Lydians invented coinage, at least in the West, although the first coins (under Alyattes I, reigned c.591–c.560 BC) were neither gold nor silver but an alloy of the two called electrum.

[53] To complement the largest denomination, fractions were made, including a hekte (sixth), hemihekte (twelfth), and so forth down to a 96th, with the 1/96 stater weighing only about 0.15 grams.

Croesus is credited with issuing the Croeseid, the first true gold coins with a standardised purity for general circulation,[50] and the world's first bimetallic monetary system circa 550 BC.

Around 550 BC, near the beginning of his reign, Croesus paid for the construction of the temple of Artemis at Ephesus, which became one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world.

Croesus was defeated in battle by Cyrus II of Persia in 546 BC, with the Lydian kingdom losing its autonomy and becoming a Persian satrapy.

His adventures in Lydia are the adventures of a Greek hero in a peripheral and foreign land: during his stay, Heracles enslaved the Itones; killed Syleus, who forced passers-by to hoe his vineyard; slew the serpent of the river Sangarios (which appears in the heavens as the constellation Ophiucus)[58] and captured the simian tricksters, the Cercopes.

[61] In contemporary scholarship, Etruscologists overwhelmingly support an indigenous origin for the Etruscans,[62][63] dismissing Herodotus' account as based on erroneous etymologies.

[65] The French scholar Dominique Briquel contends that "the story of an exodus from Lydia to Italy was a deliberate political fabrication created in the Hellenized milieu of the court at Sardis in the early 6th century BC.

This suggests Etruscans descended from the Villanovan culture,[78][79] indicating their indigenous roots, and a link between Etruria, modern Tuscany, and Lydia dating back to the Neolithic period during the migration of Early European Farmers from Anatolia to Europe.

[80] A 2021 study confirmed these findings, showing that Etruscans and Latins in the Iron Age had similar genetic profiles and were part of the European cluster.

[84] Based on limited evidence, Lydian religious practices were centred around the fertility of nature, as was common among ancient societies which depended on the successful cultivation of land.

[86] The early Lydian religion possessed at least three cultic officiants, consisting of:[106] In addition to these clerical offices, the religious role of the kings among other Anatolian peoples suggests that Lydian kings were also religious high functionaries who participated in the cult as a representative of divine power on earth and claimed their legitimacy to rule from the gods.

The ecclesiastical province of Lydia had a metropolitan diocese at Sardis and suffragan dioceses for Philadelphia, Thyatira, Tripolis, Settae, Gordus, Tralles, Silandus, Maeonia, Apollonos Hierum, Mostene, Apollonias, Attalia, Hyrcania, Bage, Balandus, Hermocapella, Hierocaesarea, Acrassus, Dalda, Stratonicia, Cerasa, Gabala, Satala, Aureliopolis and Hellenopolis.