Ancient history of Yemen

The centers of the Old South Arabian kingdoms of present-day Yemen lay around the desert area called Ramlat al-Sab'atayn, known to medieval Arab geographers as Ṣayhad.

Apart from the territory of modern Yemen, the kingdoms extended into Oman, as far as the north Arabian oasis of Lihyan (also called Dedan), to Eritrea, and even along coastal East Africa to what is now Tanzania.

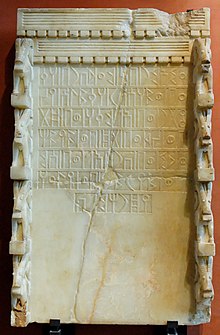

This stage of investigation reached its climax with the travels of the Frenchman Joseph Halévy[4] 1869/70 and the Austrian Eduard Glaser 1882–1894, who together either copied or brought back to Europe some 2500 inscriptions.

The Second World War brought in a new phase of scientific preoccupation with ancient Yemen: in 1950–1952 the American Foundation for the Study of Man, founded by Wendell Phillips,[6] undertook large-scale excavations in Timna and Ma'rib, in which William Foxwell Albright and Fr.

In addition, the French excavations of 1975–1987 in Shabwah and in other locations, the Italian investigations of Paleolithic remains and the work of the German Archaeological Institute in the Ma'rib area are particularly noteworthy.

The predominant part of the inscriptions originates from Saba' and from the Sabaeo-Himyaritic Kingdom which succeeded it, the least come from Awsān, which only existed as an independent state for a short time.

On the basis of the study of a rock inscription at Ma'rib ("Glaser 1703") A. G. Lundin and Hermann von Wissmann dated the beginning of Saba' back into the 12th or the 8th century BCE.

At the time of the earliest historical sources originating in South Arabia the territory was under the rule of the Kingdom of Saba', the centres of which were situated to the east of present-day Sana'a in Ṣirwāḥ and Ma'rib.

The formation of the Minaean Kingdom in the river oasis of al-Jawf, north-west of Saba' in the 6th century BCE, actually posed a danger for Sabaean hegemony, but Yitha'amar Bayyin II, who had completed the great reservoir dam of Ma'rib, succeeded in reconquering the northern part of South Arabia.

[15] For centuries, the Sabaeans controlled outbound trade across the Bab-el-Mandeb, a strait separating the Arabian Peninsula from the Horn of Africa and the Red Sea from the Indian Ocean.

[16] Agriculture in Yemen thrived during this time due to an advanced irrigation system which consisted of large water tunnels in mountains, and dams.

The most impressive of these earthworks, known as the Ma'rib Dam was built c. 700 BCE, provided irrigation for about 25,000 acres (101 km²) of land[17] and stood for over a millennium, finally collapsing in 570 CE after centuries of neglect.

It was first referenced by an outside civilization in an Old Sabaic inscription of Karab'il Watar from the early 7th century BCE, in which the King of Ḥaḑramawtt, Yada'il, is mentioned as being one of his allies.

Minaic inscriptions have been found far afield of the Kingdom of Ma'in, as far away as al-Ūlā in northwestern Saudi Arabia and even on the island of Delos and in Egypt.

From their capital city, the Ḥimyarite kings launched successful military campaigns, and had stretched its domain at times as far east to the Persian Gulf and as far north as the Arabian Desert.

GDRT of Aksum began to interfere in South Arabian affairs, signing an alliance with Saba', and a Ḥimyarite text notes that Ḥaḑramawt and Qatabān were also all allied against the kingdom.

Ḥimyar then allied with Saba' and invaded the newly taken Aksumite territories, retaking Ẓifār, which had been under the control of GDRT's son BYGT, and pushing Aksum back into the Tihāmah.

Sharahil had reinforcements from the Bedouins of the Kinda and Madh'hij tribes, eventually wiping out the Christian community in Najran by means of execution and forced conversion to Judaism.

[34] Esimiphaios was a local Christian lord, mentioned in an inscription celebrating the burning of an ancient Sabaean palace in Marib to build a church on its ruins.

[39] According to the later Arabic sources, Kaleb retaliated by sending a force of 3,000 men under a relative, but the troops defected and killed their leader, and a second attempt at reigning in the rebellious Abrahah also failed.

[40][41] Later Ethiopian sources state that Kaleb abdicated to live out his years in a monastery and sent his crown to be hung in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

An inscription of Sumyafa' Ashwa' also mentions two kings (nagaśt) of Aksum, indicating that the two may have co-ruled for a while before Kaleb abdicated in favor of Alla Amidas.

[40] Procopius notes that Abrahah later submitted to Kaleb's successor, as supported by the former's inscription in 543 stating Aksum before the territories directly under his control.

During his reign, Abrahah repaired the Ma'rib Dam in 543, and received embassies from Persia and Byzantium, including a request to free some bishops who had been imprisoned at Nisibis (according to John of Ephesus's "Life of Simeon").

Aksum (called "Yaksum" in Arabic sources) was perplexingly referred to as "of Ma'afir" (ḏū maʻāfir), the southwestern coast of Yemen, in Abrahah's Ma'rib dam inscription, and was succeeded by his brother, Masrūq.

Aksumite control in Yemen ended in 570 with the invasion of the elder Sassanid general Vahriz who, according to later legends, famously killed Masrūq with his well-aimed arrow.

[38] The exact chronology of the early wars are uncertain, as a 525 inscription mentions the death of a King of Ḥimyar, which could refer either to the Ḥimyarite viceroy of Aksum, Sumyafa' Ashwa', or to Yusuf Asar Yathar.

[27] Emperor Khosrow I sent troops under the command of Wahrez, who helped the semi-legendary Sayf ibn Dhi Yazan to drive the Kingdom of Aksum out of Yemen.

This development was a consequence of the expansionary policy pursued by the Sassanian king Khosrow II (590–628), whose aim was to secure Persian border areas such as Yemen against Roman and Byzantine incursions.