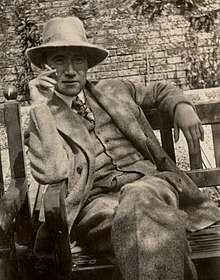

André Gide

"[1] Known for his fiction as well as his autobiographical works, Gide expressed the conflict and eventual reconciliation of the two sides of his personality (characterized by a Protestant austerity and a transgressive sexual adventurousness, respectively).

As a self-professed pederast, he used his writing to explore his struggle to be fully oneself, including owning one's sexual nature, without betraying one's values.

His father Jean Paul Guillaume Gide was a professor of law at University of Paris; he died in 1880, when the boy was eleven years old.

The ancestral Guidos had moved to France and other western and northern European countries after converting to Protestantism during the 16th century, and facing persecution in Catholic Italy.

Whilst there he worked on the second chapter of Strait Is the Gate (French: La Porte étroite), and van Rysselberghe painted his portrait.

He would appear in a red waistcoat, black velvet jacket and beige-coloured trousers and, in lieu of collar and tie, a loosely knotted scarf.

[12] Together they were part of the Foyer Franco-Belge, in which capacity they worked to find employment, food and housing for Franco-Belgian refugees who arrived in Paris following the 1914 German invasion of Belgium.

He had known her for a long time, as she was the daughter of his friends Maria Monnom and Théo van Rysselberghe, a Belgian neo-impressionist painter.

This caused the only crisis in the long-standing relationship between Allégret and Gide, and damaged his friendship with Théo van Rysselberghe.

Elisabeth eventually left her husband to move to Paris and manage the practical aspects of Gide's life (they had adjoining apartments built on the rue Vavin).

Later he explored their unconsummated marriage in Et nunc manet in te, his memoir of Madeleine, published in English in the United States in 1952.

The government had conceded part of the colony to French companies, allowing them to exploit the area's natural resources, in particular rubber.

He related that native workers were forced to leave their village for several weeks to collect rubber in the forest, and compared their exploitation by the companies to slavery.

The book contributed to the growing anti-colonialism movements in France and helped thinkers to re-evaluate the effects of colonialism in Africa.

Gide insisted on the release of Victor Serge, a Soviet writer and a member of the Left Opposition who was prosecuted by the Stalinist regime for his views.

[24] While admitting the economic and social achievements of the USSR compared to the Russian Empire, he noted the decay of culture, the erasure of the individuality of Soviet citizens, and the suppression of any dissent: Then would it not be better to, instead of playing on words, simply to acknowledge that the revolutionary spirit (or even simply the critical spirit) is no longer the correct thing, that it is not wanted any more?

[24] In Afterthoughts, Gide is more direct in his criticism of the Soviet society: "Citrine, Trotsky, Mercier, Yvon, Victor Serge, Leguay, Rudolf and many others have helped me with their documentation.

[29] The main points of Afterthoughts were that the dictatorship of the proletariat became the dictatorship of Stalin, and that the privileged bureaucracy became the new ruling class which profited by the workers' surplus labour, spending the state budget on projects like the Palace of Soviets or to raise its own standards of living, while the working class lived in extreme poverty; Gide cited the official Soviet newspapers to prove his statements.

In Thesee, written in 1946, he showed that an individual may safely leave the Maze only if "he had clung tightly to the thread which linked him with the past".

He also said that he remained an individualist and protested against "the submersion of individual responsibility in organized authority, in that escape from freedom which is characteristic of our age.

[22] In 1930 Gide published a book about the Blanche Monnier case titled La Séquestrée de Poitiers, changing little but the names of the protagonists.

He left France for Africa in 1942 and lived in Tunis from December 1942 until it was re-taken by French, British and American forces in May 1943 and he was able to travel to Algiers where he stayed until the end of World War II.

[33] In 1947, he received the Nobel Prize in Literature "for his comprehensive and artistically significant writings, in which human problems and conditions have been presented with a fearless love of truth and keen psychological insight".

It was the life of a man engaging not only in the business of artistic creation, but reflecting on that process in his journal, reading that work to his friends and discussing it with them; a man who knew and corresponded with all the major literary figures of his own country and with many in Germany and England; who found daily nourishment in the Latin, French, English and German classics, and, for much of his life, in the Bible; [who enjoyed playing Chopin and other classic works on the piano;] and who engaged in commenting on the moral, political and sexual questions of the day.

"[39] André Gide's writings spanned many genres – "As a master of prose narrative, occasional dramatist and translator, literary critic, letter writer, essayist, and diarist, André Gide provided twentieth-century French literature with one of its most intriguing examples of the man of letters.

Here, too, we see Gide's curiosity, his youthfulness, at work: a refusal to mine only one seam, to repeat successful formulas...The fiction spans the early years of Symbolism, to the "comic, more inventive, even fantastic" pieces, to the later "serious, heavily autobiographical, first-person narratives"...In France Gide was considered a great stylist in the classical sense, "with his clear, succinct, spare, deliberately, subtly phrased sentences."

), are much rarer, and the sodomites much more numerous, than I first thought...That such loves can spring up, that such relationships can be formed, it is not enough for me to say that this is natural; I maintain that it is good; each of the two finds exaltation, protection, a challenge in them; and I wonder whether it is for the youth or the elder man that they are more profitable.

Wilde took a key out of his pocket and showed me into a tiny apartment of two rooms...The youths followed him, each of them wrapped in a burnous that hid his face.

Every time since then that I have sought after pleasure, it is the memory of that night I have pursued...My joy was unbounded, and I cannot imagine it greater, even if love had been added.

But what name then am I to give the rapture I felt as I clasped in my naked arms that perfect little body, so wild, so ardent, so sombrely lascivious?