Andreas Palaiologos

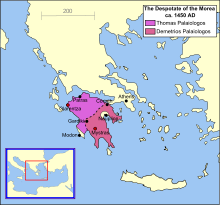

After his father's death in 1465, Andreas was recognized as the titular Despot of the Morea and from 1483 onwards, he also claimed the title "Emperor of Constantinople" (Latin: Imperator Constantinopolitanus).

After Thomas died in 1465, the then twelve-year-old Andreas moved to Rome and, as the eldest nephew of Constantine XI, became the head of the Palaiologos family and the chief claimant to the ancient imperial throne.

The Byzantine Empire, once extending throughout the eastern Mediterranean, was more or less reduced to the imperial capital of Constantinople itself, the Peloponnese and a handful of islands in the Aegean Sea, and was forced to pay tribute to the Ottomans.

[13] As the empire dwindled, the emperors came to the conclusion that the only way to ensure that their remaining territory was kept intact was to grant some of their holdings to their sons or brothers, who received the title of despot, as appanages to defend and govern.

Inspired by the writings of West-oriented intellectuals such as Demetrios Kydones and Manuel Chrysoloras, the Palaiologan emperors believed that if they could only convince the popes of their lack of heresy, the papacy would unleash large western armies to relieve them.

Andreas, his younger brother Manuel, and their sister Zoe, accompanied by their guardian and some exiled Byzantine nobles, arrived at Ancona, but they never met their father, who died on 12 May.

[29] Perhaps in response to feeling as if he was not receiving the respect due to him, Andreas eventually started styling himself as the "Emperor of Constantinople" (Latin: Imperator Constantinopolitanus),[9] a title never adopted by his father.

[8] One of Thomas Palaiologos's advisors from Patras, George Sphrantzes, visited Andreas in 1466 and recognized him as "the successor and heir of the Palaiologan dynasty" and his rightful ruler.

By the 1480s, the papacy had become the new patron of some of his presumed companions, such as Theodore Tzamblacon "of Constantinople", Catherine Zamplaconissa, Euphrasina Palaiologina, Thomasina Cantacuzene and several Greeks described as "de Morea", including a man called Constantine, and the two women Theodorina and Megalia.

[41] Andreas traveled to southern Italy, the obvious rallying point for an attack through Greece, and was at Foggia in October with several of his close companions, including the aforementioned Manuel Palaiologos, George Pagumenos and Michael Aristoboulos.

In August 1480, they had been repulsed with heavy losses in the siege of Rhodes, and Mehmed II's death on 3 May was followed by a civil war between his sons Cem and Bayezid over who was to seize power.

By October, the situation had grown unfavorable: Bayezid was well-established as Sultan and the major Christian realms of Western Europe were too disunited to join and wage war on the Ottomans.

Historians, following the writings of contemporary writer Gherardi da Volterra, have alleged that Pope Sixtus IV gave Andreas 3000 ducats to finance the expedition.

English historian Jonathan Harris believes that it is more likely that the money was simply an advance payment for his travels in southern Italy since it did not cover any extra costs outside the regular expenditure of Andreas and his household.

[50] In the 1490s, King Charles VIII of France was actively planning a crusade against the Ottomans, but he was also involved in a struggle to gain control of the Kingdom of Naples in southern Italy.

The French Cardinal Raymond Peraudi was passionately devoted to Charles's crusading plans and was against him getting embroiled in Italian politics, believing that war against Naples would prove a fatal diversion from attacking the Ottomans.

In return for being granted his ancestral lands (once he had been restored in the Morea), Andreas's feudal tax to Charles would consist of one white saddle horse every year.

The plan was perfect for Alexander VI, who, like Peraudi, hoped that the French armies marching through Italy were intended to be used against the Ottomans in defense of Christendom and not against Naples.

[9] In the meantime, Charles took care to support "our great friend" (Latin: magnus amicus noster) Andreas, and on 14 May 1495 awarded him an annual pension of 1200 ducats.

[6] Like his predecessor Charles VIII, Louis XII also invaded Italy, as part of the Second Italian War (1499–1504), and during this time presented himself as a would-be crusader ostensibly headed for Constantinople and Jerusalem.

Bishop Jacques Volaterranus wrote of the poor spectacle Andreas and his entourage made at Rome, covered in rags rather than the purple and silk vestments he had formerly always worn.

In his will, written on 7 April that same year, he once more gave away his claim to the imperial title, this time to Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile,[5][67] designating them and their successors as his universal heirs.

[5] On 17 July 1499, Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan, reported that he had sent "Don Fernando, son of the Despot of the Morea, nephew of the lord Constantine [Arianiti, governor of Montferrat], to the Turk with five horses",[74] possibly a diplomatic or espionage mission.

[5] Theodore Paleologus, who lived in Cornwall in the 17th century and claimed descent from Thomas Palaiologos through an otherwise unattested son called John, might be a descendant of Andreas instead, but his lineage is uncertain.

Scottish historian George Finlay wrote in 1877 of the fate of Andreas that it "hardly merits the attention of history, were it not that mankind has a morbid curiosity concerning the fortunes of the most worthless princes".

According to Jonathan Harris, who in 1995 offered a more redeeming view of Andreas, he is typically characterized as "an immoral and extravagant playboy who squandered his generous papal pension on loose living and eventually died in poverty".

[21] The financial situation of the Palaiologoi in the 1470s to 1490s must have been considered precarious for Andreas to sell his titular claims and for Manuel to travel Europe in hopes of employment and eventually reach the Ottomans in Constantinople.

[79] As the Palaiologan emperors had done before them, both Thomas and Andreas continued to cling to the ultimately unsuccessful plan of securing papal aid for a grand campaign of reconquest and restoration.

[18] Ultimately, Andreas's life was not a great success, and his dreams of restoring the Byzantine Empire were dashed by continually having to raise funds to support himself and his household.

His difficult situation was not his fault, and though the degradation of papal support is the most direct cause for his hardships, the failure ultimately was in the Palaiologan policy of looking to the West for aid itself.