Angkor

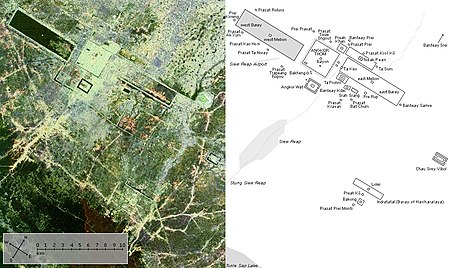

In 2007, an international team of researchers using satellite photographs and other modern techniques concluded that Angkor had been the largest pre-industrial city in the world by surface area, with an elaborate infrastructure system connecting an urban sprawl of at least 1,000 square kilometres (390 sq mi) to the well-known temples at its core.

[4] Although the size of its population remains a topic of research and debate, newly identified agricultural systems in the Angkor area may have supported between 750,000 and one million people.

According to Sdok Kok Thom inscription,[6][7] circa 781 Indrapura was the first capital of Jayavarman II, located in Banteay Prei Nokor, near today's Kompong Cham.

In 802, Jayavarman articulated his new status by declaring himself "universal monarch" (chakravartin) and, in a move that was to be imitated by his successors and that linked him to the cult of Siva, taking on the epithet of "god-king" (devaraja).

[13] A great king and an accomplished builder, he was celebrated by one inscription as "a lion-man; he tore the enemy with the claws of his grandeur; his teeth were his policies; his eyes were the Veda.

[16] The significance of such reservoirs has been debated by modern scholars, some of whom have seen in them a means of irrigating rice fields, and others of whom have regarded them as religiously charged symbols of the great mythological oceans surrounding Mount Meru, the abode of the gods.

[16] In accordance with this cosmic symbolism, Yasovarman built his central temple on a low hill known as Phnom Bakheng, surrounding it with a moat fed from the baray.

However, a specific area of at least 1,000 km2 (390 sq mi) beyond the major temples is defined by a complex system of infrastructure, including roads and canals that indicate a high degree of connectivity and functional integration with the urban core.

[20][21] After consolidating his political position through military campaigns, diplomacy, and a firm domestic administration, Suryavarman launched into the construction of Angkor Wat as his personal temple mausoleum.

In one of the scenes, the king himself is portrayed as larger in size than his subjects, sitting cross-legged on an elevated throne and holding court, while a bevy of attendants make him comfortable with the aid of parasols and fans.

Jayavarman oversaw the period of Angkor's most prolific construction, which included building of the well-known temples of Ta Prohm and Preah Khan, dedicating them to his parents.

Some of the topics he addressed in the account were those of religion, justice, kingship, societal norms, agriculture, slavery, birds, vegetables, bathing, clothing, tools, draft animals, and commerce.

[26][27] In one passage, he described a royal procession consisting of soldiers, numerous servant women and concubines, ministers and princes, and finally, "the sovereign, standing on an elephant, holding his sacred sword in his hand."

[26][28] The end of the Angkorian period is generally set as 1431, the year Angkor was sacked and looted by Suphannaphum-Mon dynasty of Ayutthaya invaders, though the civilization already had been in decline in the 13th and 14th centuries.

Ongoing civil wars with the Lavo-Khmer and Suphannaphum-Mon dynasty of Ayutthaya were already sapping the strength of Angkor at the time of Zhou Daguan toward the end of the 13th century.

Some scholars have connected the decline of Angkor with the conversion of the Khmer Empire to Theravada Buddhism following the reign of Jayavarman VII, arguing that this religious transition eroded the Hindu concept of kingship that underpinned the Angkorian civilization.

[36] Other scholars attempting to account for the rapid decline and abandonment of Angkor have hypothesized natural disasters such as disease (Bubonic Plague), earthquakes, inundations, or drastic climate changes as the relevant agents of destruction.

[37] Recent research by Australian archaeologists suggests that the decline may have been due to a shortage of water caused by the transition from the Medieval Warm Period to the Little Ice Age.

[38] LDEO dendrochronological research has established tree-ring chronologies indicating severe periods of drought across mainland Southeast Asia in the early 15th century, raising the possibility that Angkor's canals and reservoirs ran dry and ended expansion of available farmland.

[41] While Angkor was known to the local Khmer and was shown to European visitors; Henri Mouhot in 1860 and Anna Leonowens in 1865,[42] it remained cloaked by the forest until the end of the 19th century.

In addition, scholars associated with the school including George Coedès, Maurice Glaize, Paul Mus, Philippe Stern and others initiated a program of historical scholarship and interpretation that is fundamental to the current understanding of Angkor.

[43] The World Monuments Fund has aided Preah Khan, the Churning of the Sea of Milk (a 49-meter-long bas-relief frieze in Angkor Wat), Ta Som, and Phnom Bakheng.

[54] Temples from the period of Chenla bear stone inscriptions, in both Sanskrit and Khmer, naming both Hindu and local ancestral deities, with Shiva supreme among the former.

[57] The Khmer king Jayavarman II, whose assumption of power around 800 AD marks the beginning of the Angkorian period, established his capital at a place called Hariharalaya (today known as Roluos), at the northern end of the great lake, Tonlé Sap.

During the reign of Jayavarman II, the single-chambered sanctuaries typical of Chenla gave way to temples constructed as a series of raised platforms bearing multiple towers.

[64] Similarly, Rajendravarman, whose reign began in 944 AD, constructed the temple of Pre Rup, the central tower of which housed the royal lingam called Rajendrabhadresvara.

[66] Religious syncretism, however, remained thoroughgoing in Khmer society: the state religion of Shaivism was not necessarily abrogated by Suryavarman's turn to Vishnu, and the temple may well have housed a royal lingam.

In the last quarter of the 12th century, King Jayavarman VII departed radically from the tradition of his predecessors when he adopted Mahayana Buddhism as his personal faith.

Jayavarman also made Buddhism the state religion of his kingdom when he constructed the Buddhist temple known as the Bayon at the heart of his new capital city of Angkor Thom.

The next king, Jayavarman VIII, was a Shaivite iconoclast who specialized in destroying Buddhist images and in reestablishing the Hindu shrines that his illustrious predecessor had converted to Buddhism.