Anglo-German Naval Agreement

The Anglo-German Naval Agreement was an ambitious attempt on the part of both the British and the Germans to reach better relations, but it ultimately foundered because of conflicting expectations between the two countries.

In Britain, where after 1919 guilt was felt over what was seen as the excessively harsh terms of Versailles, the German claim to "equality" in armaments often met with considerable sympathy.

[5] The British attitude was well summarised in a Foreign Office memo from 1935 that stated "... from the earliest years following the war it was our policy to eliminate those parts of the Peace Settlement which, as practical people, we knew to be unstable and indefensible".

[13] As part of the effort to do away with the Panzerschiffe, the British Admiralty stated in March 1932 and again in the spring of 1933 that Germany was entitled to "a moral right to some relaxation of the treaty [of Versailles]".

To lure the Germans back to Geneva, after several months of strong diplomatic pressure by London on Paris, all of the other delegations voted for a British-sponsored resolution in December 1932 that would allow for the "theoretical equality of rights in a system which would provide security for all nations".

Thus, before Hitler had become chancellor, it had been accepted that Germany could rearm beyond the limits set by Versailles, but the precise extent of German rearmament was still open to negotiation.

[18] In return for such a "renunciation", Hitler expected an Anglo-German alliance directed at France and the Soviet Union and British support for the German efforts to acquire Lebensraum in Eastern Europe.

As the first step towards the Anglo-German alliance, Hitler had written in Mein Kampf of his intention to seek a "sea pact", by which Germany would "renounce" any naval challenge against Britain.

[21] In November 1934, the Germans formally informed the British of their wish to reach a treaty under which the Reichsmarine would be allowed to grow until the size of 35% of the Royal Navy.

[28] On 2 May 1935, Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald told the House of Commons of his government's intention to reach a naval pact to regulate the future growth of the German Navy.

In March 1934, a British Foreign Office memo stated, "Part V of the Treaty of Versailles... is, for practical purposes, dead, and it would become a putrefying corpse which, if left unburied, would soon poison the political atmosphere of Europe.

[30] At the same meeting, Simon stated, "Germany would prefer, it appears, to be 'made an honest woman'; but if she is left too long to indulge in illegitimate practices and to find by experience that she does not suffer for it, this laudable ambition may wear off".

In the interval between his "recovering" and Simon's visit, the German government took the chance of formally rejecting all the clauses of Versailles relating to land and air disarmament.

[36] Sir Eric Phipps, the British ambassador in Berlin, advised London that no chance at a naval agreement with Germany should be lost "owing to French shortsightedness".

German Foreign Minister Baron Konstantin von Neurath was at first opposed to the arrangement but changed his mind when he decided that the British would never accept the 35:100 ratio and so having Ribbentrop head the mission was the best way to discredit his rival.

[44][45] The Naval Pact was signed in London on 18 June 1935 without the British government consulting with France and Italy or later informing them of the secret agreements, which stipulated that the Germans could build in certain categories more powerful warships than any of the three other major Western European nations then possessed.

[46] As an additional insult for France, the Naval Pact was signed on the 120th anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo, in which Prussian and British-led troops defeated the French under Napoleon.

[47] In practice, the lack of shipbuilding space, design problems, shortages of skilled workers and the scarcity of foreign exchange to purchase necessary raw materials slowed the rebuilding of the German Navy.

[48] The requirement for the Kriegsmarine to divide its 35% tonnage ratio by warship categories had the effect of forcing the Germans to build a symmetrical "balanced fleet" shipbuilding program that reflected the British priorities.

[50] He was critical of the existing building priorities dictated by the agreement since there was no realistic possibility of a German "balanced fleet" defeating the Royal Navy.

[55] At his meeting with British Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax in November 1937, Hitler stated that the agreement was the only item in the field of Anglo-German relations that had not been "wrecked".

[56] By 1938, the only use the Germans had for the agreement was to threaten to renounce it as a way of pressuring London to accept Continental Europe as Germany's rightful sphere of influence.

[57] At a meeting on 16 April 1938 between Sir Nevile Henderson, the British ambassador to Germany, and Hermann Göring, the latter stated it had never been valued in England and that he bitterly regretted that Herr Hitler had ever consented to it at the time without getting anything in exchange.

In view of the great existing disparities in the size of the two navies this threat could only be executed if British construction were to remain stationary over a considerable period of years whilst German tonnage was built up to it.

By making a free gift of an absence of naval competition, he hoped that relations between the two countries would be so improved that Britain should not, in fact, find it necessary to interfere with Germany's continental policy.

[61] An important sign of Hitler's changed perceptions about Britain was his decision in January 1939 to give first priority to the Kriegsmarine in allocations of money, skilled workers and raw materials and to launch Plan Z to build a colossal Kriegsmarine of 10 battleships, 16 "pocket battleships", 8 aircraft carriers, 5 heavy cruisers, 36 light cruisers and 249 U-boats by 1944, which were purposed to crush the Royal Navy.

[63] Reports received in October 1938 that the Germans were considering denouncing the agreement were used by Halifax in Cabinet discussions for the need for a tougher policy with the Reich.

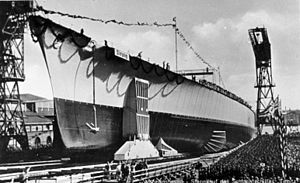

[68] In a speech in Wilhelmshaven for the launch of the battleship Tirpitz, Hitler threatened to denounce the agreement if Britain persisted with its "encirclement" policy, as was represented by the "guarantee" of Polish independence.

[69] Chatfield, now the Minister for Co-ordination of Defence, commented that Hitler had "persuaded himself" that the British had provided the Reich with a "free hand" in Eastern Europe in exchange for the agreement.

[69] Chamberlain stated that the British had never given such an understanding to Germany, and he commented that he first learned of Hitler's belief in such an implied bargain during his meeting with the Führer at the Berchtesgaden summit in September 1938.