Domestication of vertebrates

[9][10][11] Certain animal species, and certain individuals within those species, make better candidates for domestication than others because they exhibit certain behavioral characteristics: (1) the size and organization of their social structure; (2) the availability and the degree of selectivity in their choice of mates; (3) the ease and speed with which the parents bond with their young, and the maturity and mobility of the young at birth; (4) the degree of flexibility in diet and habitat tolerance; and (5) responses to humans and new environments, including flight responses and reactivity to external stimuli.

[25][26] Archaeological and genetic data suggest that long-term bidirectional gene flow between wild and domestic stocks was common is some species, including donkeys, horses, New and Old World camelids, goats, sheep, and pigs.

Domesticates have provided humans with resources that they could more predictably and securely control, move, and redistribute, which has been the advantage that had fueled a population explosion of the agro-pastoralists and their spread to all corners of the planet.

[10][35] The domestication of animals and plants was triggered by the climatic and environmental changes that occurred after the peak of the Last Glacial Maximum around 21,000 years ago and which continue to this present day.

The Younger Dryas that occurred 12,900 years ago was a period of intense cold and aridity that put pressure on humans to intensify their foraging strategies.

[38][7] Areas with increasing agriculture underwent urbanization,[38][39] developing higher-density populations[38][40] and expanded economies, and became centers of livestock and crop domestication.

In the Fertile Crescent 10,000-11,000 years ago, zooarchaeology indicates that goats, pigs, sheep, and taurine cattle were the first livestock to be domesticated.

In East Asia 8,000 years ago, pigs were domesticated from wild boar that were genetically different from those found in the Fertile Crescent.

[12] Certain animal species, and certain individuals within those species, make better candidates for domestication than others because they exhibit certain behavioral characteristics: (1) the size and organization of their social structure; (2) the availability and the degree of selectivity in their choice of mates; (3) the ease and speed with which the parents bond with their young, and the maturity and mobility of the young at birth; (4) the degree of flexibility in diet and habitat tolerance; and (5) responses to humans and new environments, including flight responses and reactivity to external stimuli.

[12][46] Foxes that had been selectively bred for tameness over 40 years had experienced a significant reduction in cranial height and width and by inference in brain size,[12][47] which supports the hypothesis that brain-size reduction is an early response to the selective pressure for tameness and lowered reactivity that is the universal feature of animal domestication.

This portion of the brain regulates endocrine function that influences behaviors such as aggression, wariness, and responses to environmentally induced stress, all attributes which are dramatically affected by domestication.

Although they do not affect the development of the adrenal cortex directly, the neural crest cells may be involved in relevant upstream embryological interactions.

[49] Furthermore, artificial selection targeting tameness may affect genes that control the concentration or movement of NCCs in the embryo, leading to a variety of phenotypes.

[49] Feral mammals such as dogs, cats, goats, donkeys, pigs, and ferrets that have lived apart from humans for generations show no sign of regaining the brain mass of their wild progenitors.

[15][56][57] In 2015, a study compared the diversity of dental size, shape and allometry across the proposed domestication categories of modern pigs (genus Sus).

Those animals that were most capable of taking advantage of the resources associated with human camps would have been the tamer, less aggressive individuals with shorter fight or flight distances.

From this perspective, animal domestication is a coevolutionary process in which a population responds to selective pressure while adapting to a novel niche that included another species with evolving behaviors.

[23] The domestication of animals commenced over 15,000 years before present (YBP), beginning with the grey wolf (Canis lupus) by nomadic hunter-gatherers.

When, where, and how many times wolves may have been domesticated remains debated because only a small number of ancient specimens have been found, and both archaeology and genetics continue to provide conflicting evidence.

Domestication was likely initiated when humans began to experiment with hunting strategies designed to increase the availability of these prey, perhaps as a response to localized pressure on the supply of the animal.

[7][12][16] Prey pathway animals include sheep, goats, cattle, water buffalo, yak, pig, reindeer, llama and alpaca.

The right conditions for the domestication for some of them appear to have been in place in the central and eastern Fertile Crescent at the end of the Younger Dryas climatic downturn and the beginning of the Early Holocene about 11,700 YBP, and by 10,000 YBP people were preferentially killing young males of a variety of species and allowed the females to live in order to produce more offspring.

[7][12] By measuring the size, sex ratios, and mortality profiles of zooarchaeological specimens, archeologists have been able to document changes in the management strategies of hunted sheep, goats, pigs, and cows in the Fertile Crescent starting 11,700 YBP.

A recent demographic and metrical study of cow and pig remains at Sha’ar Hagolan, Israel, demonstrated that both species were severely overhunted before domestication, suggesting that the intensive exploitation led to management strategies adopted throughout the region that ultimately led to the domestication of these populations following the prey pathway.

Although horses, donkeys, and Old World camels were sometimes hunted as prey species, they were each deliberately brought into the human niche for sources of transport.

[7] The archaeological and genetic data suggests that long-term bidirectional gene flow between wild and domestic stocks – including canids, donkeys, horses, New and Old World camelids, goats, sheep, and pigs – was common.

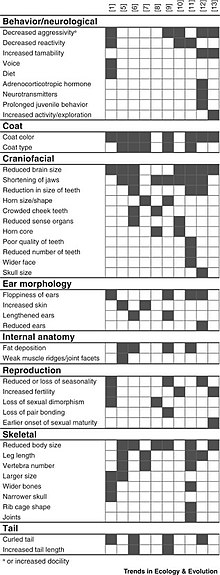

[2][3][4] Domestic animals vary in coat color, craniofacial morphology, reduced brain size, floppy ears, and changes in the endocrine system and reproductive cycle.

The domesticated silver fox experiment demonstrated that selection for tameness within a few generations can result in modified behavioral, morphological, and physiological traits.

In addition, the experiment provided a mechanism for the start of the animal domestication process that did not depend on deliberate human forethought and action.

[45] In the 1980s, a researcher used a set of behavioral, cognitive, and visible phenotypic markers, such as coat color, to produce domesticated fallow deer within a few generations.