Animal sacrifice

Animal sacrifices were common throughout Europe and the Ancient Near East until the spread of Christianity in Late Antiquity, and continue in some cultures or religions today.

[3] At a cemetery uncovered at Hierakonpolis and dated to 3000 BCE, the remains of a much wider variety of animals were found, including non-domestic species such as baboons and hippopotami, which may have been sacrificed in honor of powerful former citizens or buried near their former owners.

[5] By the end of the Copper Age in 3000 BCE, animal sacrifice had become a common practice across many cultures, and appeared to have become more generally restricted to domestic livestock.

[8] However, remains of a young goat were found in Cueva de la Dehesilla (es), a cave in Spain, related to a funerary ritual from the Middle Neolithic period, dated to between 4800 and 4000 BCE.

Unlike the Greeks, who had worked out a justification for keeping the best edible parts of the sacrifice for the assembled humans to eat, in these cultures the whole animal was normally placed on the fire by the altar and burned, or sometimes it was buried.

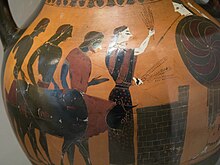

The animal, which should be perfect of its kind, is decorated with garlands and the like, and led in procession to the altar, a girl with a basket on her head containing the concealed knife leading the way.

[11] The animals used are, in order of preference, bull or ox, cow, sheep (the most common), goat, pig (with piglet the cheapest mammal), and poultry (but rarely other birds or fish).

[12] Horses and asses are seen on some vases in the Geometric style (900–750 BCE), but are very rarely mentioned in literature; they were relatively late introductions to Greece, and it has been suggested that Greek preferences in this matter go very far back.

[13] For a smaller and simpler offering, a grain of incense could be thrown on the sacred fire,[14] and outside the cities farmers made simple sacrificial gifts of plant produce as the "first fruits" were harvested.

The occasions of sacrifice in Homer's epic poems may shed some light onto the view of the gods as members of society, rather than as external entities, indicating social ties.

[19] According to the unique account by the Greek author Herodotus (c. 484 – c. 425 BCE), the Scythians sacrificed various kinds of livestock, though the most prestigious offering was considered to be the horse.

Sacrifice sought the harmonisation of the earthly and divine, so the victim must seem willing to offer its own life on behalf of the community; it must remain calm and be quickly and cleanly dispatched.

Di superi with strong connections to the earth, such as Mars, Janus, Neptune and various genii – including the Emperor's – were offered fertile victims.

In times of great crisis, the Senate could decree collective public rites, in which Rome's citizens, including women and children, moved in procession from one temple to the next, supplicating the gods.

[31] The exta were the entrails of a sacrificed animal, comprising in Cicero's enumeration the gall bladder (fel), liver (iecur), heart (cor), and lungs (pulmones).

As a product of Roman sacrifice, the exta and blood are reserved for the gods, while the meat (viscera) is shared among human beings in a communal meal.

When the deity's portion was cooked, it was sprinkled with mola salsa (ritually prepared salted flour) and wine, then placed in the fire on the altar for the offering; the technical verb for this action was porricere.

Such a ritual burial ceremony was also found among other Balkan peoples, and it has been interpreted as a trace of the cult of an agricultural deity, for it was a sacrifice that allowed the renewal of the products of the soil, giving force to the vegetation of the fields, trees and vines.

Until the 19th century, on St. Martin's Day (11 November) in rural Ireland a rooster, goose or sheep would be slaughtered and some of its blood sprinkled on the threshold of the house.

[citation needed] Practices of Hindu animal sacrifice are mostly associated with Shaktism, Shaiva Agamas and in currents of folk Hinduism called Kulamarga strongly rooted in local tribal traditions.

[citation needed] Animal sacrifices are performed mainly at temples following the Shakti school of Hinduism where the female nature of Brahman is worshipped in the form of Kali and Durga.

[78] According to Christopher Fuller, the animal sacrifice practice is rare among Hindus during Navratri, or at other times, outside the Shaktism tradition found in the eastern Indian states of West Bengal, Odisha[79] and Assam.

[86][87][88] The Rajput of Rajasthan worship their weapons and horses on Navratri, and formerly offered a sacrifice of a goat to a goddess revered as Kuldevi – a practice that continues in some places.

The text states that a human sacrifice may be performed to please the goddess, but only with the consent of prince before a war or cases of imminent danger.

[101] The ancient kings, Confucius and Confucian scholars framed the sacrificing scale of every strata from the Zhou system, not including human sacrifice, in The Book of Rites.

[106] Some animal offerings, such as fowl, pigs, goats, fish, or other livestock, are accepted in some Taoism sects and beliefs in Chinese folk religion.

In folk religion some regions believe that high-status deities prefer vegetarian food more, while ghosts, low-status gods, and other unknown supernatural spirits like meat.

[110][111] The U.S. Supreme Court's 1993 decision Church of Lukumi Babalu Aye v. City of Hialeah upheld the right of Santería adherents to practice ritual animal sacrifice in the United States of America.

Circuit Court of Appeals in the case of Jose Merced, President Templo Yoruba Omo Orisha Texas, Inc., v. City of Euless.

Atayal, Seediq and Taroko people believe that bad-luck or punishments of 'Utux', which refers to any kind of supernatural spirits or ancestors, would infect the relatives.