Dragonfly

Fossils of very large dragonfly-like insects, sometimes called griffinflies, are found from 325 million years ago (Mya) in Upper Carboniferous rocks; these had wingspans up to about 750 mm (30 in), though they were only distant relatives, not true dragonflies which first appeared during the Early Jurassic.

[20] The globe skimmer Pantala flavescens is probably the most widespread dragonfly species in the world; it is cosmopolitan, occurring on all continents in the warmer regions.

[25] In Kamchatka, only a few species of dragonfly including the treeline emerald Somatochlora arctica and some aeshnids such as Aeshna subarctica are found, possibly because of the low temperature of the lakes there.

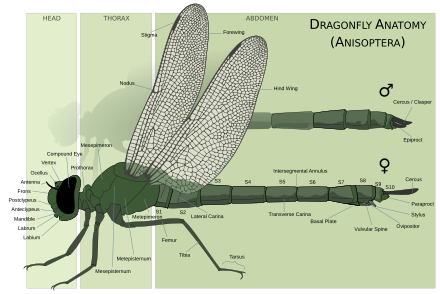

By contrast, damselflies (suborder Zygoptera) have slender bodies and fly more weakly; most species fold their wings over the abdomen when stationary, and the eyes are well separated on the sides of the head.

The mouthparts are adapted for biting with a toothed jaw; the flap-like labrum, at the front of the mouth, can be shot rapidly forward to catch prey.

The mesothorax and metathorax are fused into a rigid, box-like structure with internal bracing, and provide a robust attachment for the powerful wing muscles inside.

In females, the genital opening is on the underside of the eighth segment, and is covered by a simple flap (vulvar lamina) or an ovipositor, depending on species and the method of egg-laying.

The naiads of some clubtails (Gomphidae) that burrow into the sediment, have a snorkel-like tube at the end of the abdomen enabling them to draw in clean water while they are buried in mud.

[33] Some have their bodies covered with a pale blue, waxy powderiness called pruinosity; it wears off when scraped during mating, leaving darker areas.

[41] Some dragonflies, such as the green darner, Anax junius, have a noniridescent blue that is produced structurally by scatter from arrays of tiny spheres in the endoplasmic reticulum of epidermal cells underneath the cuticle.

[44] Adult males vigorously defend territories near water; these areas provide suitable habitat for the nymphs to develop, and for females to lay their eggs.

Most species need moderate conditions, not too eutrophic, not too acidic;[46] a few species such as Sympetrum danae (black darter) and Libellula quadrimaculata (four-spotted chaser) prefer acidic waters such as peat bogs,[47] while others such as Libellula fulva (scarce chaser) need slow-moving, eutrophic waters with reeds or similar waterside plants.

[57] Egg-laying (ovipositing) involves not only the female darting over floating or waterside vegetation to deposit eggs on a suitable substrate, but also the male hovering above her or continuing to clasp her and flying in tandem.

[44][56][55] Males use their penis and associated genital structures to compress or scrape out sperm from previous matings; this activity takes up much of the time that a copulating pair remains in the heart posture.

The female in some families (Aeshnidae, Petaluridae) has a sharp-edged ovipositor with which she slits open a stem or leaf of a plant on or near the water, so she can push her eggs inside.

It remains stationary with its head out of the water, while its respiration system adapts to breathing air, then climbs up a reed or other emergent plant, and moults (ecdysis).

Curling back upwards, it completes its emergence, swallowing air, which plumps out its body, and pumping haemolymph into its wings, which causes them to expand to their full extent.

[30] In high-speed territorial battles between male Australian emperors (Hemianax papuensis), the fighting dragonflies adjust their flight paths to appear stationary to their rivals, minimizing the chance of being detected as they approach.

This behaviour involves doing a "handstand", perching with the body raised and the abdomen pointing towards the sun, thus minimising the amount of solar radiation received.

On a hot day, dragonflies sometimes adjust their body temperature by skimming over a water surface and briefly touching it, often three times in quick succession.

[56] They are almost exclusively carnivorous, eating a wide variety of insects ranging from small midges and mosquitoes to butterflies, moths, damselflies, and smaller dragonflies.

Nymphs of Cordulegaster bidentata sometimes hunt small arthropods on the ground at night, while some species in the Anax genus have even been observed leaping out of the water to attack and kill full-grown tree frogs.

These include falcons such as the American kestrel, the merlin,[82] and the hobby;[83] nighthawks, swifts, flycatchers and swallows also take some adults; some species of wasps, too, prey on dragonflies, using them to provision their nests, laying an egg on each captured insect.

[87] Trematodes are parasites of vertebrates such as frogs, with complex life cycles often involving a period as a stage called a cercaria in a secondary host, a snail.

The damming of rivers for hydroelectric schemes and the drainage of low-lying land has reduced suitable habitat, as has pollution and the introduction of alien species.

[93] The dragonfly's long lifespan and low population density makes it vulnerable to disturbance, such as from collisions with vehicles on roads built near wetlands.

[94] Dragonflies are attracted to shiny surfaces that produce polarization which they can mistake for water, and they have been known to aggregate close to polished gravestones, solar panels, automobiles, and other such structures on which they attempt to lay eggs.

Often stylized in a double-barred cross design, dragonflies are a common motif in Zuni pottery, as well as Hopi rock art and Pueblo necklaces.

[110][111] The watercolourist Moses Harris (1731–1785), known for his The Aurelian or natural history of English insects (1766), published in 1780, the first scientific descriptions of several Odonata including the banded demoiselle, Calopteryx splendens.

[113] In heraldry, like other winged insects, the dragonfly is typically depicted tergiant (with its back facing the viewer), with its head to chief (at the top).