Anti-clerical riots of 1835

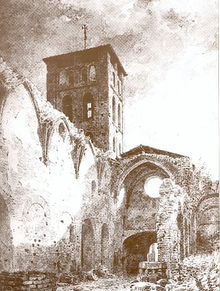

The anti-clerical riots of 1835 were revolts against the religious orders in Spain, fundamentally for their support of the Carlists in the civil war that began after the death of King Ferdinand VII at the end of 1833, and which took place during the summer of 1835 in Aragon and, above all, in Catalonia, within the context of the uprisings of the Spanish Liberal Revolution that sought to put an end to the regime of the Royal Statute, implemented in 1834 by the regent María Cristina de Borbón-Dos Sicilias, and to give way to a constitutional monarchy with the reestablishment of the Constitution of 1812.

"All the revolutionary movements that broke out in several cities during the summer of 1835 and manifested themselves in the burning of convents and in the repudiation of the Royal Statute have the same common denominator: hostility to the regulars, motivated either by their intervention in the repression after the Liberal Triennium, or by their sympathies for Carlism.

"[1] At the end of July 1834 the Cortes were opened, convened according to the provisions of the Royal Statute, a kind of granted charter promulgated by María Cristina de Borbón-Dos Sicilias, who ruled the throne on behalf of her daughter, the future Isabella II, who was then four years old, and whose succession rights had not been recognized by the Carlists, the supporters of the brother of the recently deceased King Ferdinand VII, Carlos María Isidro de Borbón, who did not accept the Pragmatic Sanction of 1830 that abolished the Salic Law that did not allow women to reign, so he lost his rights to the throne in favor of his brother's newborn daughter.

Thus the procurators Joaquín María López, Fermín Caballero and the Count of Las Navas, addressed a letter to the regent in which they asked for a declaration of the political rights of the Spaniards, but the government of the moderate liberal Francisco Martínez de la Rosa rejected it.

Months later a Law of City Councils began to be discussed so that at least at the local level the representative regime derived from the principle of national sovereignty would be accepted, but again the government did not admit it, although it meant an enormous attrition, and this together with the adverse march of the civil war caused its fall on July 6, 1835.

[3] The anticlerical riot of Zaragoza on July 6, had an antecedent in the spring, on April 3, when a multitude went to the archiepiscopal palace to protest against the decision of its holder Bernardo Francés Caballero, of absolutist ideas -although he had not made any manifestation favorable to the cause of the Carlists-, for having withdrawn the licenses of confession and preaching to two clergymen who were chaplains of the urban militia for their reproachable conduct -in a letter sent on April 18 to the government the archbishop accused them of leading a licentious life-.

[7] The government, for its part, dismissed the captain general, whom the newspaper La Abeja of July 13 accused of having given arms to men of the proletarian class, who would have participated in the assaults on the convents, an argument already used by the liberal press on the occasion of the massacre of friars in Madrid in 1834.

[12] "On July 11, the officers of the militia met at the University -it must be remembered that they were all landowners, merchants, liberal professions- the "honest neighbors", and presented the indispensable measures "so that order would be maintained".

The first and most urgent was to "absolutely suppress the regulars of Zaragoza", and also to separate the ideologically suspicious public employees and to speed up the work of the board appointed by the government more than a year ago for the reform of the clergy, as well as the commission of the Cortes for the freedom of the press.

Subsequently, the Junta established in Zaragoza would explain the motivations for such behavior in a text that revealed the resentment accumulated since 1823 against the clergy, to charge "a religious community to the point of superstition" with revenge as if it had been a blind and collective action, without direction, but above all to conclude before the regent, as the highest institutional authority, that if she wanted to "calm public anxiety", the "first indispensable providence" was none other than the suppression of all religious convents "declaring their buildings and goods national property".

It was the demand of the major contributors constituted in a revolutionary junta, who also defined themselves as "wealthy classes" and that in this logic of transformations, at the time of August, they could already finish their proclamation declaring themselves "as idolaters of order as of freedom".

[14] This is how a chronicler of the time explained it:[15]At half to eleven o'clock at night the town of Reus was disturbed, shooting bullets at the air, and immediately the individuals were all together, and the first thing they did was to surround the convent of San Francisco and, when the friars saw this, they rang the bell three times for help, trusting the troops that had come for their protection, which could not calm them down, because they saw that it would be bad for them.This is how the liberal newspaper El Eco del Comercio reported the news:[14] At 10 o'clock at night, gathering in one of the many and growing groups that had scattered in the town, after having forcibly removed all the fuel they could find from the brick kilns.

Thus assembled, they ran in droves to San Francisco, set fire to the building, and at the same time stabbed with knives as many friars as they could find.According to Antonio Moliner Prada, the ultimate cause of the riot was to be found in "the anti-clericalism that was felt in many places, as well as the help that some convents gave to the Carlists, or the importance that a future disentailment could have".

In the streets of the city it was common to hear songs like "Mentre hi hagi frares, mai anirem be" ("While there are friars we will never go well") or to call them "paparres" ("ticks") and sometimes they even received "trunks, stones and even some bricks and a slap", according to a canon.

The liberal newspaper El Vapor explained with a notable detachment and without providing many details of what had happened, nor of the death of "a few" friars:[20] On the afternoon of the 25th the people went on a rampage in the bullring, on the occasion of the bulls being too peaceful to give interest to the fight.

(...) The account of the events published in the London newspaper The Times of August 7, whose author witnessed the assault on these convents, also coincides with these appreciations:[21]The confusion produced by the circumstances and the numerous attempts at robbery were overcome by the impetus shown in this horrible work of destruction.

Those who defend the conspiratorial thesis affirm that everything was prepared in a secret meeting that took place in a house located in the Rambla de Santa Monica and that the rioters, who were paid, were given the incendiary material.

The resounding clamor of the mobs that gave the assault, or celebrated the triumph, could be heard everywhere; the trampling of the horses and the shouts of the chiefs that demanded order filled the intervals of silence left by them.... Few, very few were those who committed these vandalic attacks, but the spectators were infinite.Ana María García Rovira, on the contrary, affirms that the movement was spontaneous, although she points out that prominent liberals, such as the printer and publisher M. Rivadeneyra, participated in the uproar, trying to organize the popular unrest.

[9] This same point of view is defended by Josep Fontana, for whom it seems clear that "a group of liberals, dissatisfied with the regime of the Royal Statute, allowed it to happen, thinking that this explosion of popular unrest could be useful to accelerate the political evolution in its advanced sense".

The people are still alive who, with the ruling baton in their hands, contemplated both scenes, and do not believe, gentlemen, that there is any exaggeration in this, because I was in the square and I remember very well how shocked I was to hear that the authority ordered those who were tearing up the benches to try not to harm themselves (...) It was a question of overthrowing a ministry [a government] and of embarking on a different path from the one that this ministry was following (...).A similar line is the one maintained by Juan Sisinio Pérez Garzón who emphasizes that in the riot participated relevant social sectors "that lead the popular anger".

As evidence, he points out that in the convents "incendiary bottles of turpentine were used, like "Molotov cocktails", which someone had prepared" and that it was repeated, as in the massacre of the friars in Madrid in 1834, "the institutional quietude of the militia and troops and of the authorities".

One of those responsible was Captain General Manuel Llauder who stirred up the most radical sector of the liberals and the popular strata when in a fleeting appearance in Barcelona he published a proclamation in which he threatened to punish those guilty of the assaults on the convents.

It seems that the factory fire was an act of "ludismo" as an observer of the time warned in an article that appeared in El Vapor six months later: "I do not know that in the popular movements the plebs go to the treasuries or bank houses, doing it very often to the production establishments whose machines make personal work unnecessary".

[25] This is also confirmed by the report written by the military governor of Barcelona, General Pastor, about what happened:[26] The authorities, upon learning that the rioters were attempting this attack, sent all the force they could muster, in order to stop the fire; but to no avail, because they were determined to do so, convinced that the looms moved by machines diminished the production of manual labor.

This is how A. Fernandez de los Rios recounted the exclaustration that Salustiano Olózaga led in Madrid twenty years later:[30]The operation was done with great ease: most of the friars were dressed in profane clothes, and few asked for company to leave the convents, of which they left with the alacrity of those who had the move arranged and organized in advance.

Cantero was right: in his district there were one hundred and so many Capuchins of Patience.Julio Caro Baroja has drawn attention to the figure of the old exclaustrated friar, because unlike the young man who worked wherever he could or joined the Carlist ranks -or that of the national militiamen-, he lived "enduring his misery, emaciated, weakened, giving Latin classes in schools, or doing other poorly paid jobs".

Caro Baroja quotes the progressive liberal Fermín Caballero who in 1837, shortly after the exclaustration, wrote:[32]The total extinction of the religious orders is the most gigantic step we have taken in the present era; it is the true act of reform and revolution.

The present generation is surprised not to find anywhere the chapels and habits that it has seen since childhood, of such varied forms and shades as the names of the Benedictines, Geronimos, Mostenses, Basilians, Franciscans, Capuchins, Gilitos, etc., were multiplied, but our successors will no less admire the transformation, when traditionally only through books they know what the friars were and how they ended up, and when to learn about their costumes they have to go to the prints or museums!