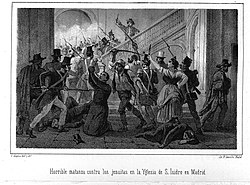

1834 massacre of friars in Madrid

[3] In April 1834 the regent María Cristina de Borbón-Dos Sicilias promulgated the Royal Statute, a kind of granted charter by which she intended to gain the support of the liberals for the cause of her daughter, the future Isabella II, who was then four years old, and whose inheritance rights had not been recognized by the Carlists, the supporters of the brother of the recently deceased King Ferdinand VII, Carlos María Isidro de Borbón, who did not accept the Pragmatic Sanction of 1830 that abolished the Salic Law that did not allow women to reign, so he lost his rights to the throne in favor of his brother's daughter.

During the two years that the epidemic lasted, it caused more than one hundred thousand deaths throughout Spain and half a million people fell ill.[5] Rodil's army, coming from the border of Portugal, followed the path of the cholera epidemic that had isolated Andalusia and that had forced the establishment of sanitary fences in La Mancha, but it was not prevented from entering Madrid, from where it was heading north to relieve the troops of General Vicente Genaro de Quesada, who were unable to control the Carlist rebels.

[1] On July 15, news reached Madrid that Rodil's army had not been able to contain the Carlists either and that the pretender Carlos María Isidro de Borbón had entered Spain, proclaiming it in a manifesto from Elizondo.

[6] On the very day that the bad news about the progress of the first Carlist war reached Madrid, the epidemic broke out again, "the sick died by the hundreds, with the horrifying circumstances that accompany such a cruel plague", according to Alcalá Galiano's account.

[9] The rumor that "the water of the public fountains had been poisoned by the friars", especially by the Jesuits, was reinforced by the fact that some of them in the previous days had explained the cholera epidemic as "divine punishment against the unbelieving inhabitants of the city, while the people of the countryside remained free because they were faithful and devout".

Everything took place in the most central area of Madrid, between Puerta del Sol, Plaza de la Cebada, the convent of San Francisco el Grande and the streets of Atocha and Toledo.

xxvii), it was a frequent prank, which was "commonly punished with a slap in the face", but on that occasion it was taken as an excuse to blame the friars, when the news spread through the corridors, proclaimed by spontaneous speakers, that "of the two boys who had been surprised [.

"The pretext, to corroborate the version that since the previous day had spread about two women cigarette sellers from the nearby tobacco factory, they said they were surprised with poison powder to pour into the fountains and that they were paid by the Jesuits.

The troops arrive after half an hour with none other than the captain general and police superintendent, Martínez de San Martín, an expert in repressing riots of the exalted liberals during the constitutional triennium in Madrid.

There, in addition to killing seven friars in the presence of the troops, who did nothing to prevent it, the mutineers carried out burlesque acts by dressing up in liturgical clothes and forming a sacrilegious dance that continued along the streets of Atocha and Carretas.

Around nine o'clock at night the convent of San Francisco el Grande was assaulted, where forty-three Franciscan friars were murdered (or fifty, according to other sources) in the midst of macabre scenes, while the officers of the regiment of the Princess, billeted on the premises, failed to give any order to intervene to the more than one thousand soldiers who composed it.

[11] On July 19, the government of Francisco Martínez de la Rosa, in view of the ambiguity and the notorious passivity and even connivance with the mutiny of the different authorities -military and municipal-, arrested and imprisoned Captain General Martínez de San Martín, who had a troop of nine thousand men to have prevented the assaults and murders, and forced the corregidor, the Marquis of Falces, and the civil governor, the Duke of Gor, to resign, as the most responsible of the urban militia, many of whose members had had a very active participation in the events.

[15] "The commanders of the militia were forced by the discredit of this institution to address an exposition to the queen in order to save its good name, in which they asked for its reform to avoid the entry of undesirable persons into the corps".

[11] The defenders of the first thesis, such as Stanley G. Payne, affirm that the rumor about the poisoned wells that triggered the anticlerical mutiny would have been spread by radical secret societies -although not necessarily Freemasonry-.

The people, then, carried out a typical "projection", attributing to the political enemies not only true intentions, but others imagined, fantastic and adjusted to a procedure that is known to us, for the repeated in different circumstances, throughout History.An in-between position is held by Juan Sisinio Perez Garzon who affirms "that it is not incompatible the existence of an organizational plot to destroy the ecclesiastical power and to overthrow the government, with the fact that this one overlaps and takes advantage of a situation of popular exasperation - by the cholera - to sow terror among the friars and to use a tactic of panic to justify the assault to the clerical possessions".

[26] According to this historian, the way in which the liberal newspaper El Eco del Comercio reported the news of the riot would constitute an indication of who could have been behind the events when it transformed the victims into "enemies of the Motherland", the lynching of the religious was reduced to the concept of "some misfortunes" and affirmed that in the assaults "it is said that some evidence was discovered that gave foundation to the voices that have run in the previous days about their plan for the poisoning of the waters.

Everything can be believed of the perversity of the enemies of the Motherland, and we have always foreseen that they would take advantage of the present moments to increase the conflict in which we are..."[27] A similar position is held by Antonio Moliner Prada when he recognizes "that the radical liberals were interested in accelerating the process of the Revolution and were interested in political destabilization and direct attacks on the Church", but he goes on to point out that the "accumulated secular hatred against the clergy manifested itself in all its crudeness during those days and served as a precedent for the anticlerical riots that were repeated during the summer of 1835 in some cities.

The participation of the people in the events of 1835 would make clear to the progressive liberals what they had already sensed in 1834, the need to establish a strategy that would avoid the radicalization of the process of the Revolution and could challenge the new bourgeois order that they were trying to consolidate".