Anti-union violence

On some occasions, violence in labor disputes may be purposeful and calculated,[2] for example the hiring and deployment of goon squads to assault strikers.

The 1887 Thibodaux massacre in Louisiana, the 1899 Pana riot in southern Illinois, and the 1911 Queen & Crescent killings in Kentucky and Tennessee are three examples of deliberate campaigns of murder against organized black workers in the American south, the first committed by landowners, the other two by white competitors.

In a similar way the strike of Asturian miners in 1934, put down by right-wing Spanish government forces with great loss of life, amounted to an insurrection through work stoppage, not an economic labor action.

After coming to power as chancellor in January 1933, Adolf Hitler declared May Day a national holiday, then on May 2, 1933, unexpectedly moved to outlaw labor unions as part of the Nazi "synchronization" process.

Major unions such as the Allgemeiner Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund were raided that day, their accounts seized, and their leaders (Gustav Schiefer, Wilhelm Leuschner, Erich Luebbe) arrested and sent to concentration camps.

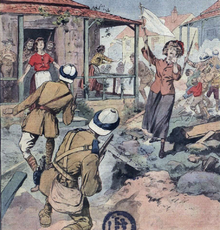

[11] Some anti-union violence appears to be random, such as an incident during the 1912 textile strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in which a police officer fired into a crowd of strikers, killing Anna LoPizzo.

Three years after Frank Little was lynched, a strike by Butte miners was suppressed with gunfire when deputized mine guards suddenly fired upon unarmed picketers in the Anaconda Road Massacre.

[15] Other anti-union violence may seem orchestrated, as in 1914 when mine guards and the state militia fired into a tent colony of striking miners in Colorado, an incident that came to be known as the Ludlow Massacre.

[16] During that strike, the company hired the Baldwin Felts agency, which built an armored car so their agents could approach the strikers' tent colonies with impunity.

In an auto workers strike organised by Victor Reuther and others in 1937, "[u]nionists assembled rocks, steel hinges, and other objects to throw at the cops, and police organized tear gas attacks and mounted charges.

[34] In the book From Blackjacks To Briefcases, Robert Michael Smith states that during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, anti-union agencies "spawned violence and wreaked havoc" on the labor movement.

[36] Harry Wellington Laidler wrote a book in 1913 detailing how one of the largest union busters in the United States, Corporations Auxiliary Company, had a sales pitch offering the use of provocation and violence.

[16] During that strike, the company hired the Baldwin Felts agency, which built an armored car so their agents could approach the strikers' tent colonies with impunity.

In 1917, union organizer Frank Little was hanged from a railroad trestle in Butte, Montana, with a note pinned to his body which carried a "warning" to other labor activists.

Rosvall and Voutilainen were murdered for their pro-union efforts resulting in the authorities in Thunder Bay conducting a major cover up in an attempt to conceal the truth.