Anti-intellectualism

The new rulers of Cambodia call 1975 "Year Zero", the dawn of an age in which there will be no families, no sentiment, no expressions of love or grief, no medicines, no hospitals, no schools, no books, no learning, no holidays, no music, no song, no post, no money – only work and death.

[5] Ideologically-extreme dictatorships who mean to recreate a society such as the Khmer Rouge rule of Cambodia (1975–1979) pre-emptively killed potential political opponents, especially the educated middle-class and the intelligentsia.

[6][7] In opposition to the military repression of free speech, biochemist César Milstein said ironically: "Our country would be put in order, as soon as all the intellectuals who were meddling in the region were expelled."

"[10] In the U.S., the conservative[11] American economist Thomas Sowell argued for distinctions between unreasonable and reasonable wariness of intellectuals in their influence upon the institutions of a society.

In the book Intellectuals and Society (2009), Sowell said:[12] By encouraging, or even requiring, students to take stands where they have neither the knowledge nor the intellectual training to seriously examine complex issues, teachers promote the expression of unsubstantiated opinions, the venting of uninformed emotions, and the habit of acting on those opinions and emotions, while ignoring or dismissing opposing views, without having either the intellectual equipment or the personal experience to weigh one view against another in any serious way.Hence, school teachers are part of the intelligentsia who recruit children in elementary school and teach them politics—to advocate for or to advocate against public policy—as part of community-service projects; which political experience later assists them in earning admission to a university.

In that manner, the intellectuals of a society intervene and participate in social arenas of which they might not possess expert knowledge, and so unduly influence the formulation and realization of public policy.

In the event, teaching political advocacy in elementary school encourages students to formulate opinions "without any intellectual training or prior knowledge of those issues, making constraints against falsity few or non-existent.

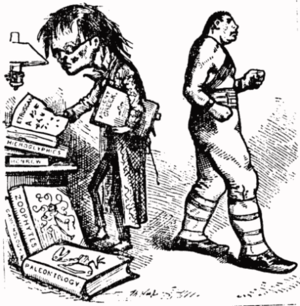

"[14] In that vein, "In the Land of the Rococo Marxists" (2000), the American writer Tom Wolfe characterized the intellectual as "a person knowledgeable in one field, who speaks out only in others.

[17] Yet, not every Puritan concurred with Cotton's religious contempt for secular education, such as John Harvard, a major early benefactor of the university which now bears his name.

The rise of American society to pre-eminence, as an economic, political, and military power, was thus the triumph of the common man, and a slap across the face to the presumptions of the arrogant, whether an elite of blood or books.In U.S. history, the advocacy and acceptability of anti-intellectualism has varied, in part because the majority of Americans lived a rural life of arduous manual labor and agricultural work prior to the industrialization of the late nineteenth century.

Bayard R. Hall, A.M., said about frontier Indiana:[17] We always preferred an ignorant, bad man to a talented one, and, hence, attempts were usually made to ruin the moral character of a smart candidate; since, unhappily, smartness and wickedness were supposed to be generally coupled, and [like-wise] incompetence and goodness.Yet, the "real-life" redemption of the egghead American intellectual was possible if he embraced the mores and values of mainstream society; thus, in the fiction of O. Henry, a character notes that once an East Coast university graduate "gets over" his intellectual vanity he no longer thinks himself better than other men, realizing he makes just as good a cowboy as any other young man, despite his common-man counterpart being the slow-witted naïf of good heart, a pop culture stereotype from stage shows.

The strain of anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that 'my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge'.

The English, therefore, tend to respect class-based distinctions in birth, wealth, status, manners, and speech, while Americans resent them.Such social resentment characterises contemporary political discussions about the socio-political functions of mass-communication media and science; that is, scientific facts, generally accepted by educated people throughout the world, are misrepresented as opinions in the U.S., specifically about climate science and global warming.

[25] Miami University anthropology professor Homayun Sidky has argued that 21st-century anti-scientific and pseudoscientific approaches to knowledge, particularly in the United States, are rooted in a postmodernist "decades-long academic assault on science:" "Many of those indoctrinated in postmodern anti-science went on to become conservative political and religious leaders, policymakers, journalists, journal editors, judges, lawyers, and members of city councils and school boards.

"[26] In 2017, a Pew Research Center poll revealed that a majority of American Republicans thought colleges and universities have a negative impact on the United States, and in 2019, academics Adam Waters and E.J.

[35] At universities, student anti-intellectualism has resulted in the social acceptability of cheating on schoolwork, especially in the business schools, a manifestation of ethically expedient cognitive dissonance rather than of academic critical thinking.

[46] Moreover, in the book Inventing the Egghead: The Battle over Brainpower in American Culture (2013), Aaron Lecklider indicated that the contemporary ideological dismissal of the intelligentsia derived from the corporate media's reactionary misrepresentations of intellectual men and women as lacking the common-sense of regular folk.

[48] At the beginning of World War II, the Soviet secret police carried out mass executions of the Polish intelligentsia and military leadership in the 1940 Katyn massacre.

Hence the Fascist rejection of materialist logic, because it relies upon a priori principles improperly counter-changed with a posteriori ones that are irrelevant to the matter-in-hand in deciding whether or not to act.

Moreover, this fascist philosophy occurred parallel to Actual Idealism, his philosophic system; he opposed intellectualism for its being disconnected from the active intelligence that gets things done, i.e. thought is killed when its constituent parts are labelled, and thus rendered as discrete entities.

This eventually led to the loss of most ancient works of literature and philosophy when Xiang Yu burned down the Qin palace in 208 BC.

The Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) was a politically violent decade which saw wide-ranging social engineering throughout the People's Republic of China by its leader Chairman Mao Zedong.

To that effect, China's youth nationally organized themselves into Red Guards and hunted the "liberal bourgeois" elements who were supposedly subverting the CCP and Chinese society.

The Red Guards were particularly aggressive when they attacked their teachers and professors, causing most schools and universities to be shut down once the Cultural Revolution began.

When the Communist Party of Kampuchea and the Khmer Rouge (1951–1981) established their regime as Democratic Kampuchea (1975–1979) in Cambodia, their anti-intellectualism which idealised the country and demonised the cities was immediately imposed on the country in order to establish agrarian socialism, thus, they emptied cities in order to purge the Khmer nation of every traitor, enemy of the state and intellectual, often symbolised by eyeglasses.

[52] The event has been described by historians as a decapitation strike,[53][54] the purpose of which was intended to deprive the Armenian population of an intellectual leadership and a chance to resist.