Antigenic variation

Antigenic variation can occur by altering a variety of surface molecules including proteins and carbohydrates.

Antigenic variation can result from gene conversion,[1] site-specific DNA inversions,[2] hypermutation,[3] or recombination of sequence cassettes.

In the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, the cause of Lyme disease, the surface lipoprotein VlsE can undergo recombination which results in antigenic diversity.

The bacterium carries a plasmid that contains fifteen silent vls cassettes and one functional copy of vlsE.

Segments of the silent cassettes recombine with the vlsE gene, generating variants of the surface lipoprotein antigen.

To protect itself, the parasite decorates itself with a dense, homogeneous coat (~10^7 molecules) of the variant surface glycoprotein (VSG).

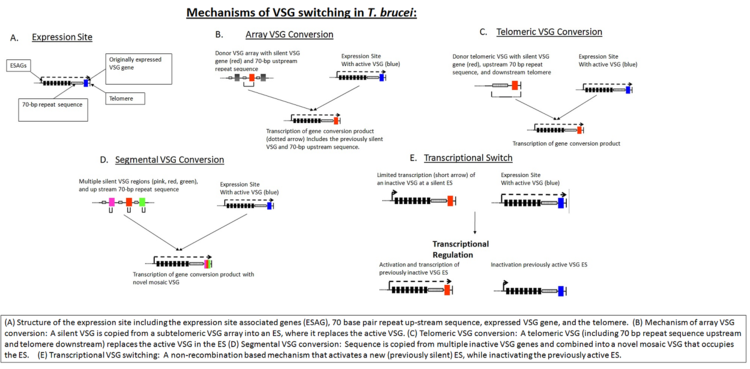

[9] This process is partially dependent on homologous recombination of DNA, which is mediated in part by the interaction of the T. brucei BRCA2 gene with RAD51 (however, this is not the only possible mechanism, as BRCA2 variants still display some VSG switching).

[9] In addition to homologous recombination, transcriptional regulation is also important in antigen switching, since T. brucei has multiple potential expression sites.

While in the human host, the parasite spends most of its life cycle within hepatic cells and erythrocytes (in contrast to T. brucei which remains extracellular).

The diversity of the gene family is further increased via a number of different mechanisms including exchange of genetic information at telomeric loci, as well as meiotic recombination.

[14] Fluorescent in situ hybridization analysis has shown that activation of var alleles is linked to altered positioning of the genetic material to distinct "transcriptionally permissive" areas.

Antigenic shift occurs periodically when the genes for structural proteins are acquired from other animal hosts resulting in a sudden dramatic change in viral genome.

These maps can show how changes in amino acids can alter the binding of an antibody to virus particle and help to analyze the pattern of genetic and antigenic evolution.

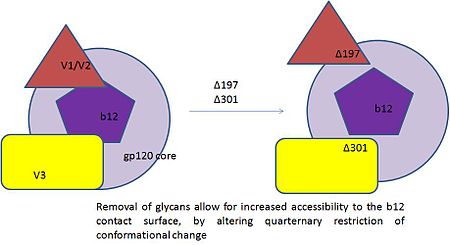

Recent findings show that resistance to neutralization by b12 was an outcome of substitutions that resided in the region proximal to CD4 contact surface.

The genus Flavivirus has a prototypical envelope protein (E-protein) on its surface which serves as the target for virus neutralizing antibodies.

If mutation in a critical amino acid can dramatically alter neutralization by antibodies then WNV vaccines and diagnostic assays becomes difficult to rely on.

Other flaviviruses that cause dengue, louping ill and yellow fever escape antibody neutralization via mutations in the domain III of the E protein.