Antigen

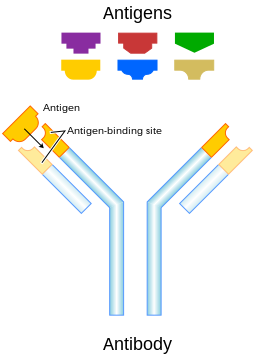

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule, moiety, foreign particulate matter, or an allergen, such as pollen, that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor.

[7] Paul Ehrlich coined the term antibody (German: Antikörper) in his side-chain theory at the end of the 19th century.

For T-cell receptor (TCR) recognition, the peptide must be processed into small fragments inside the cell and presented by a major histocompatibility complex (MHC).

[13] Similarly, the adjuvant component of vaccines plays an essential role in the activation of the innate immune system.

[14][15] An immunogen is an antigen substance (or adduct) that is able to trigger a humoral (innate) or cell-mediated immune response.

[4] This includes parts (coats, capsules, cell walls, flagella, fimbriae, and toxins) of bacteria, viruses, and other microorganisms.

Non-microbial non-self antigens can include pollen, egg white, and proteins from transplanted tissues and organs or on the surface of transfused blood cells.

APCs then present the fragments to T helper cells (CD4+) by the use of class II histocompatibility molecules on their surface.

[2] An autoantigen is usually a self-protein or protein complex (and sometimes DNA or RNA) that is recognized by the immune system of patients with a specific autoimmune disease.

Under normal conditions, these self-proteins should not be the target of the immune system, but in autoimmune diseases, their associated T cells are not deleted and instead attack.

[18] For human tumors without a viral etiology, novel peptides (neo-epitopes) are created by tumor-specific DNA alterations.

Deep-sequencing technologies can identify mutations within the protein-coding part of the genome (the exome) and predict potential neoantigens.

Exome–based analyses were exploited in a clinical setting, to assess reactivity in patients treated by either tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) cell therapy or checkpoint blockade.

However, the vast majority of mutations within expressed genes do not produce neoantigens that are recognized by autologous T cells.

[18] As of 2015 mass spectrometry resolution is insufficient to exclude many false positives from the pool of peptides that may be presented by MHC molecules.

These algorithms consider factors such as the likelihood of proteasomal processing, transport into the endoplasmic reticulum, affinity for the relevant MHC class I alleles and gene expression or protein translation levels.

[18] The majority of human neoantigens identified in unbiased screens display a high predicted MHC binding affinity.