Antiparticle

Otherwise, for each pair of antiparticle partners, one is designated as the normal particle (the one that occurs in matter usually interacted with in daily life).

The discovery of charge parity violation helped to shed light on this problem by showing that this symmetry, originally thought to be perfect, was only approximate.

Because charge is conserved, it is not possible to create an antiparticle without either destroying another particle of the same charge (as is for instance the case when antiparticles are produced naturally via beta decay or the collision of cosmic rays with Earth's atmosphere), or by the simultaneous creation of both a particle and its antiparticle (pair production), which can occur in particle accelerators such as the Large Hadron Collider at CERN.

In 1932, soon after the prediction of positrons by Paul Dirac, Carl D. Anderson found that cosmic-ray collisions produced these particles in a cloud chamber – a particle detector in which moving electrons (or positrons) leave behind trails as they move through the gas.

The electric charge-to-mass ratio of a particle can be measured by observing the radius of curling of its cloud-chamber track in a magnetic field.

The antiproton and antineutron were found by Emilio Segrè and Owen Chamberlain in 1955 at the University of California, Berkeley.

In recent years, complete atoms of antimatter have been assembled out of antiprotons and positrons, collected in electromagnetic traps.

[2] ... the development of quantum field theory made the interpretation of antiparticles as holes unnecessary, even though it lingers on in many textbooks.

To prevent this unphysical situation from happening, Dirac proposed that a "sea" of negative-energy electrons fills the universe, already occupying all of the lower-energy states so that, due to the Pauli exclusion principle, no other electron could fall into them.

But, when lifted out, it would leave behind a hole in the sea that would act exactly like a positive-energy electron with a reversed charge.

This picture implied an infinite negative charge for the universe – a problem of which Dirac was aware.

Dirac tried to argue that this was due to the electromagnetic interactions with the sea, until Hermann Weyl proved that hole theory was completely symmetric between negative and positive charges.

Robert Oppenheimer and Igor Tamm, however, proved that this would cause ordinary matter to disappear too fast.

A year later, in 1931, Dirac modified his theory and postulated the positron, a new particle of the same mass as the electron.

A unified interpretation of antiparticles is now available in quantum field theory, which solves both these problems by describing antimatter as negative energy states of the same underlying matter field, i.e. particles moving backwards in time.

The single-photon annihilation of an electron-positron pair, e− + e+ → γ, cannot occur in free space because it is impossible to conserve energy and momentum together in this process.

However, in the Coulomb field of a nucleus the translational invariance is broken and single-photon annihilation may occur.

These processes are important in the vacuum state and renormalization of a quantum field theory.

It also opens the way for neutral particle mixing through processes such as the one pictured here, which is a complicated example of mass renormalization.

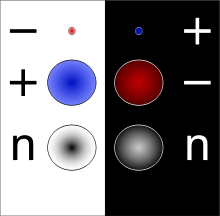

Quantum states of a particle and an antiparticle are interchanged by the combined application of charge conjugation

can be defined separately on the particles and antiparticles, then where the proportionality sign indicates that there might be a phase on the right hand side.

One may try to quantize an electron field without mixing the annihilation and creation operators by writing where we use the symbol k to denote the quantum numbers p and σ of the previous section and the sign of the energy, E(k), and ak denotes the corresponding annihilation operators.

So one has to introduce the charge conjugate antiparticle field, with its own creation and annihilation operators satisfying the relations where k has the same p, and opposite σ and sign of the energy.

Analysis of the properties of ak and bk shows that one is the annihilation operator for particles and the other for antiparticles.

By considering the propagation of the negative energy modes of the electron field backward in time, Ernst Stückelberg reached a pictorial understanding of the fact that the particle and antiparticle have equal mass m and spin J but opposite charges q.

In Feynman diagrams, anti-particles are shown traveling backwards in time relative to normal matter, and vice versa.

[12] This technique is the most widespread method of computing amplitudes in quantum field theory today.

Since this picture was first developed by Stückelberg,[13] and acquired its modern form in Feynman's work,[14] it is called the Feynman–Stückelberg interpretation of antiparticles to honor both scientists.