History of subatomic physics

According to Jain leaders like Parshvanatha and Mahavira, the ajiva (non living part of universe) consists of matter or pudgala, of definite or indefinite shape which is made up tiny uncountable and invisible particles called permanu.

Those early ideas were founded through abstract, philosophical reasoning rather than experimentation and empirical observation and represented only one line of thought among many.

In the 19th century, John Dalton, through his work on stoichiometry, concluded that each chemical element was composed of a single, unique type of particle.

Dalton and his contemporaries believed those were the fundamental particles of nature and thus named them atoms, after the Greek word atomos, meaning "indivisible"[3] or "uncut".

Throughout the 1800s scientists explored many phenomena of electricity and magnetism, culminating in an accurate theory by James Clerk Maxwell.

[5]: 77 The electron was discovered between 1879 and 1897 in works of William Crookes, Arthur Schuster, J. J. Thomson, and other physicists; its charge was carefully measured by Robert Andrews Millikan and Harvey Fletcher in their oil drop experiment of 1909.

In 1909 Ernest Rutherford and Thomas Royds demonstrated that an alpha particle combines with two electrons and forms a helium atom.

By 1914, experiments by Ernest Rutherford, Henry Moseley, James Franck and Gustav Hertz had largely established the structure of an atom as a dense nucleus of positive charge surrounded by lower-mass electrons.

The development in the nascent quantum physics, such as Bohr model, led to the understanding of chemistry in terms of the arrangement of electrons in the mostly empty volume of atoms.

Aston conclusively demonstrated existence of isotopes, whose nuclei have different masses in spite of identical atomic numbers.

Practically it appears as an intrinsic angular momentum of a particle, that is unrelated to its motion but is linked with some other features like a magnetic dipole.

To make a nuclide with more than 100 protons per nucleus one has to use an inventory and methods of particle physics (see details below), namely to accelerate and collide atomic nuclei.

Production of progressively heavier synthetic elements continued into 21st century as a branch of nuclear physics, but only for scientific purposes.

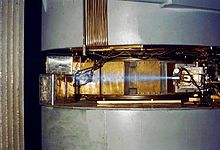

In the 1950s, with development of particle accelerators and studies of cosmic rays, inelastic scattering experiments on protons (and other atomic nuclei) with energies about hundreds of MeVs became affordable.

Murray Gell-Mann and Yuval Ne'eman brought some order to mesons and baryons, the most numerous classes of particles, by classifying them according to certain qualities.

It began with what Gell-Mann referred to as the "Eightfold Way", but proceeding into several different "octets" and "decuplets" which could predict new particles, most famously the Ω−, which was detected at Brookhaven National Laboratory in 1964, and which gave rise to the quark model of hadron composition.

Namely: The next step was a reduction in number of fundamental interactions, envisaged by early 20th century physicists as the "united field theory".

This development culminated in the completion of the theory called the Standard Model in the 1970s, that included also the strong interaction, thus covering three fundamental forces.

After the discovery, made at CERN, of the existence of neutral weak currents,[7][8][9][10] mediated by the Z boson foreseen in the standard model, the physicists Salam, Glashow and Weinberg received the 1979 Nobel Prize in Physics for their electroweak theory.

"[13] This state of affairs should not be viewed as a crisis in physics, but rather, as David Gross has said, "the kind of acceptable scientific confusion that discovery eventually transcends.

The latter possibilities are particularly exciting to physicists since they could point the way to new deeper ideas, beyond the Standard Model, about the nature of reality.

[15] Joe Incandela, of the University of California, Santa Barbara, said, "It's something that may, in the end, be one of the biggest observations of any new phenomena in our field in the last 30 or 40 years, going way back to the discovery of quarks, for example.

Michael Turner, a cosmologist at the University of Chicago and the chairman of the physics center board, said This is a big moment for particle physics and a crossroads — will this be the high water mark or will it be the first of many discoveries that point us toward solving the really big questions that we have posed?Confirmation of the Higgs boson or something very much like it would constitute a rendezvous with destiny for a generation of physicists who have believed the boson existed for half a century without ever seeing it.

Further, it affirms a grand view of a universe ruled by simple and elegant and symmetrical laws, but in which everything interesting in it being a result of flaws or breaks in that symmetry.

[15] According to the Standard Model, the Higgs boson is the only visible and particular manifestation of an invisible force field that permeates space and imbues elementary particles that would otherwise be massless with mass.

Without this Higgs field, or something like it, physicists say all the elementary forms of matter would zoom around at the speed of light; there would be neither atoms nor life.

[15] One implication of their theory was that this Higgs field would produce its own quantum particle if hit hard enough by the right amount of energy.

[15][better source needed] Further experiments continued and in March 2013 it was tentatively confirmed that the newly discovered particle was a Higgs Boson.

1s 2s 2 p (3 items).

All complete subshells (including 2p) are inherently spherically symmetric , but it is convenient to assign to "distinct" p-electrons these two-lobed shapes.