Discovery of human antiquity

In 1863 T. H. Huxley argued that man was an evolved species; and in 1864 Alfred Russel Wallace combined natural selection with the issue of antiquity.

William Benjamin Carpenter wrote in 1872 of a fixed conviction of the "modern origin" as the only reason for resisting the human creation of flint implements.

There was interest in matters arising from modification of the biblical narrative, therefore, and it was fuelled by the new knowledge of the world in early modern Europe, and then by the growth of the sciences.

Isaac La Peyrère appealed in formulating his Preadamite theory of polygenism to Jewish tradition; it was intended to be compatible with the biblical creation of man.

[7][8] This idea of humans before Adam had been current in earlier Christian scholars and those of unorthodox and heretical beliefs; La Peyrère's significance was his synthesis of the dissent.

[10] The biblical narrative had implications for ethnology (division into Hamitic, Japhetic and Semitic peoples), and had its defenders, as well as those who felt it made significant omissions.

Matthew Hale wrote his Primitive Origination of Mankind (1677) against La Peyrère, it has been suggested, in order to defend the propositions of a young human race and universal Flood, and the Native Americans as descended from Noah.

[11] Anthony John Maas writing in the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia commented that pro-slavery sentiment indirectly supported the Preadamite theories of the middle of the 19th century.

[8] The antiquity of man found support in the opposed theories of monogenism of this time that justified abolitionism by discrediting scientific racism.

[8] James Cowles Prichard argued against polygenism, wishing to support the account drawn from the Book of Genesis of a single human origin.

[14] One of La Peyrère's propositions, that China was at least 10,000 years old, gained wider currency;[15] Martino Martini had provided details of traditional Chinese chronology, from which it was deduced by Isaac Vossius that Noah's Flood was local rather than universal.

[17] In a 19th-century sequel, Alfred Russel Wallace in an 1867 book review pointed to the Pacific Islanders as posing a problem for those holding both to monogenism and a recent date for human origins.

[18] A significant consequence of the recognition of the antiquity of man was the greater scope for conjectural history, in particular for all aspects of diffusionism and social evolutionism.

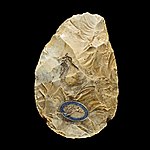

The early example of the Gray's Inn Lane Hand Axe was from gravel in a bed of a tributary of the River Thames, but remained isolated for about a century.

Thomsen's book in Danish, Ledetraad til Nordisk Oldkyndighed, was translated into German (Leitfaden zur Nordischen Alterthumskunde, 1837), and English (Guide to Northern Archæology, 1848).

The 1847 book Antiquités Celtiques et Antediluviennes by Boucher de Perthes about Saint-Acheul was found unconvincing in its presentation, until it was reconsidered about a decade later.

The debate moved on only in the context of It was this combination, "extinct faunal remains" + "human artifacts", that provided the evidence that came to be seen as crucial.

Besides Hugh Falconer who had pressed for it, the committee comprised Charles Lyell, Richard Owen, William Pengelly, Joseph Prestwich, and Andrew Ramsay.

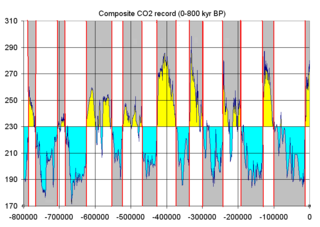

John Lubbock outlined in 1890 the way the antiquity of man had in his time been established as derived from change in prehistory: in fauna, geography and climate.

George Berkeley argued in Alciphron that the lack of human artifacts in deeper excavations suggested a recent origin of man.

[33] Uniformitarianism held the field against the competitor theories of Neptunism and catastrophism, which partook of Romantic science and theological cosmogony; it established itself as the successor of Plutonism, and became the foundation of modern geology.

[34][35] Of Lubbock's three types of change, the geographical included the theory of migration over land bridges in biogeography, which in general acted as an explanatory stopgap, rather than in most cases being one supported by science.

Georges Cuvier's Recherches sur les ossements fossiles de quadrupèdes (1812) had accepted facts of the extinctions of mammals that were to be relevant to human antiquity.

Joseph Prestwich and John Evans in April 1859, and Charles Lyell with others also in 1859, made field trips to the sites, and returned convinced that humans had coexisted with extinct mammals.

In general and qualitative terms, Lyell felt the evidence established the "antiquity of man": that humans were much older than the traditional assumptions had made them.

[37] This debate was concurrent with that over the book On the Origin of Species, published in 1859, and was evidently related; but was not one in which Charles Darwin initially made his own views public.