Book of Revelation

He then describes a series of prophetic visions, including figures such as the Seven-Headed Dragon, the Serpent, and the Beast, which culminate in the Second Coming of Jesus.

Futurists, meanwhile, believe that Revelation describes future events with the seven churches growing into the body of believers throughout the age, and a reemergence or continuous rule of a Greco-Roman system with modern capabilities described by John in ways familiar to him; and idealist or symbolic interpretations consider that Revelation does not refer to actual people or events but is an allegory of the spiritual path and the ongoing struggle between good and evil.

[4] While the dominant genre is apocalyptic, the author sees himself as a Christian prophet: Revelation uses the word in various forms 21 times, more than any other New Testament book.

[27][28] Eastern Christians became skeptical of the book as doubts concerning its authorship and unusual style[29] were reinforced by aversion to its acceptance by Montanists and other groups considered to be heretical.

[42] The Decretum Gelasianum, which is a work written by an anonymous scholar between 519 and 553, contains a list of books of scripture presented as having been reckoned as canonical by the Council of Rome (AD 382).

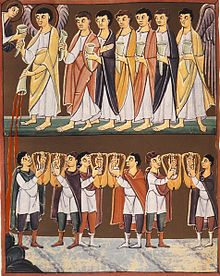

This interpretation, which has found expression among both Catholic and Protestant theologians, considers the liturgical worship, particularly the Easter rites, of early Christianity as background and context for understanding the Book of Revelation's structure and significance.

This perspective is explained in The Paschal Liturgy and the Apocalypse (new edition, 2004) by Massey H. Shepherd, an Episcopal scholar, and in Scott Hahn's The Lamb's Supper: The Mass as Heaven on Earth (1999), in which he states that Revelation in form is structured after creation, fall, judgment and redemption.

Those who hold this view say that the Temple's destruction (AD 70) had a profound effect on the Jewish people, not only in Jerusalem but among the Greek-speaking Jews of the Mediterranean.

According to Pope Benedict XVI some of the images of Revelation should be understood in the context of the dramatic suffering and persecution of the churches of Asia in the 1st century.

According to the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops the Book of Revelation contains an account of visions in symbolic and allegorical language borrowed extensively from the Old Testament.

"The universal church is composed of all who truly believe in Christ, but in the last days, a time of widespread apostasy, a remnant has been called out to keep the commandments of God and the faith of Jesus.

"[82] The three angels of Revelation 14 represent the people who accept the light of God's messages and go forth as his agents to sound the warning throughout the length and breadth of the earth.

[92] Doctrine and Covenants, section 77, postulates answers to specific questions regarding the symbolism contained in the Book of Revelation.

[93] Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints believe that the warning contained in Revelation 22:18–19 does not refer to the biblical canon as a whole.

He began his work, "The purpose of this book is to show that the Apocalypse is a manual of spiritual development and not, as conventionally interpreted, a cryptic history or prophecy.

[citation needed] This perspective (closely related to liberation theology) draws on the approach of Bible scholars such as Ched Myers, William Stringfellow, Richard Horsley, Daniel Berrigan, Wes Howard-Brook,[98] and Joerg Rieger.

[99] Various Christian anarchists, such as Jacques Ellul, have identified the state and political power as the Beast[100] and the events described, being their doings and results, the aforementioned 'wrath'.

In recent years, theories have arisen which concentrate upon how readers and texts interact to create meaning and which are less interested in what the original author intended.

Christina Rossetti was a Victorian poet who believed the sensual excitement of the natural world found its meaningful purpose in death and in God.

aesthetic and literary modes of interpretation have developed, which focus on Revelation as a work of art and imagination, viewing the imagery as symbolic depictions of timeless truths and the victory of good over evil.

Instead, he wanted to champion a public-spirited individualism (which he identified with the historical Jesus supplemented by an ill-defined cosmic consciousness) against its two natural enemies.

After that, Lawrence thought, the book became preoccupied with the birth of the baby messiah and "flamboyant hate and simple lust ... for the end of the world".

[121] Modern biblical scholarship attempts to understand Revelation in its 1st-century historical context within the genre of Jewish and Christian apocalyptic literature.

Consequently, the work is viewed as a warning not to conform to contemporary Greco-Roman society which John "unveils" as beastly, demonic, and subject to divine judgment.

[125] The eventual exclusion of other contemporary apocalyptic literature from the canon may throw light on the unfolding historical processes of what was officially considered orthodox, what was heterodox, and what was even heretical.

[122] Thus, the letter (written in the apocalyptic genre) is pastoral in nature (its purpose is offering hope to the downtrodden),[126] and the symbolism of Revelation is to be understood entirely within its historical, literary, and social context.

Revelation concentrates on Isaiah, Psalms, and Ezekiel, while neglecting, comparatively speaking, the books of the Pentateuch that are the dominant sources for other New Testament writers.

Ian Boxall[133] writes that Revelation "is no montage of biblical quotations (that is not John's way) but a wealth of allusions and evocations rewoven into something new and creative."

[134] Richard Bauckham has argued that John presents an early view of the Trinity through his descriptions of the visions and his identifying Jesus and the Holy Spirit with YHWH.

[136] According to James Stuart Russell, the book is an exposition of Olivet Discourse found in the Synoptic Gospels in Matthew 24 and 25, Mark 13, and Luke 21.