Archaeological ethics

Archaeologists are bound to conduct their investigations to a high standard and observe intellectual property laws, health and safety regulations, and other legal obligations.

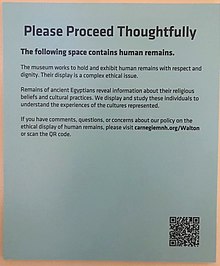

[1] Archaeologists in the field are required to work towards the preservation and management of archaeological resources, treat human remains with dignity and respect, and encourage outreach activities.

[2] Archaeologists conducting ethnoarchaeological research, which involves the study of living people, are required to follow guidelines set by the Nuremberg Code (1947) and the Declaration of Helsinki (1964).

[3] The earliest archaeologists were typically amateurs who would excavate a site with the sole purpose of collecting as many objects as they could for display in museums.

[4] Curiosity about past humans and the potential for finding lucrative and fascinating objects justified what many professional archaeologists today would consider to be unethical archaeological behavior.

[4] A series of laws passed in the 1960s and 1970s created the field of cultural resource management which protects archaeological sites from encroaching development.

[7] Where previously sites of great significance to indigenous peoples could be excavated and burials and artifacts taken to be stored in museums or sold,[8] there is now increasing awareness of taking a more respectful approach.

Technical developments in ancient DNA testing have raised more ethical questions in relation to the treatment of these human remains.

Nineteenth and twentieth century burial sites investigated by archaeologists, such as First World War graves disturbed by developments, have seen the remains of people with closely connected living relatives being exhumed and taken away.

In the United States, the bulk of modern archaeological work is done under the auspices of development by cultural resource management archaeologists[11] in compliance with Section 106[12] of the National Historic Preservation Act.

A primary ethical criticism levied against commercial archaeological practices is the prevalence of non-disclosure agreements associated with development projects involving a cultural resource management component.

[13] This practice prohibits information gathered from the archaeological record during such projects from being disseminated to the public or academic institutions for further study and peer review.

[15] This resolution has been interpreted to include not only regions where there is active military conflict but regions who have been in conflict in the past and are currently under colonial rule,[13] for example, North and South America Although not formally connected with the modern discipline of archaeology, the international trade in antiquities has also raised ethical questions regarding the ownership of archaeological artifacts.

[24] This code further provides an ethical framework for conducting contractual archaeology, fieldwork training, and journal publications.

[26] The AAA code of ethics highlights issues such as gaining informed consent, rights of indigenous people, and conservation of heritage sites.

Many archaeologists in the West today are employees of national governments or are privately employed instruments of government-derived archaeology legislation.

A famous example is the corps of archaeologists employed by Adolf Hitler to excavate in central Europe in the hope of finding evidence for a region-wide Aryan culture.

Questions regarding the ethical validity of government heritage policies and whether they sufficiently protect important remains are raised during cases such as High Speed 1 in London where burials at a cemetery at St Pancras railway station were hurriedly dug using a JCB and mistreated in order to keep an important infrastructure project on schedule.

[29][30][31] In 1972, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City purchased the Euphronious Krater, a vase used for mixing wine and water from a collector named Robert Hecht for $1,000,000.

[32][33] Another issue is the question of whether unthreatened archaeological remains should be excavated (and therefore destroyed) or preserved intact for future generations to investigate with potentially less invasive technology.

Some archaeological guidance such as PPG 16 has established a strong ethical argument for only excavating sites threatened with destruction.