Archpoet

[4] Knowledge about him comes essentially from his poems found in manuscripts:[5] his noble birth[6] in an unspecified region of Western Europe,[7][8] his respectable and classical education,[9][10] his association with Archchancellor Rainald of Dassel's court,[11] and his poetic activity linked to it in both content and purpose.

[21] Also, in poem X, Peter Dronke writes, "he counts himself among the iuvenes: while technically a iuvenis can be any age between twenty-one and fifty, it would seem plausible to imagine the Archpoet as thirty or thirty-five at the time of this composition, and to set his birth not too far from 1130.

[24] It was probably then that he began working—possibly as a "dictamen", a "master of the art of writing letters"[16]—at the court of Rainald of Dassel, the bishop elector of Cologne and Archchancellor to Frederick Barbarossa, Holy Roman Emperor,[24] about which he wrote, according to Ernst Robert Curtius, "[t]he most brilliant stanzas"[25] among the many written about and/or for him during the 35 years of his reign.

His references to Salerno, Vienna, and Cologne in his poems, as well as several details gleaned from the Archchancellor's court displacements, suggest that he did travel around northern Italy, Provence, Burgundy, Austria and Germany during his life.

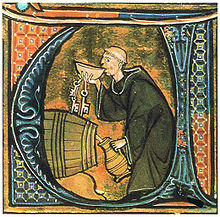

While it is still commonly assumed that the Archpoet was a follower of the Goliard tradition—writing student drinking songs, parodies critical of the Church and satires on the life of itinerant clergy in the Middle Ages—, the noted scholar Peter Dronke proposed a very different portrait in his 1968 book The Medieval Lyric: [H]e was in fact a court poet, perhaps also a civil servant or minor diplomat, in the service of the Imperial Chancellor, and so almost certainly a member of the circle around Frederick Barbarossa himself.

Despite being quite dissimilar from one another in terms of tone and intent, the ten poems are all "occasional"[12] in the sense that they have been written for a specific purpose under precise circumstances, whether to celebrate an event or respond to a request; in the Archpoet's case, concerning the court of his patron: eight of them are directed to Rainald of Dassel, while the two others are addressed to Frederick Barbarossa himself.

[4] For example, the fourth poem, "Archicancellarie, vir discrete mentis", was most probably written as a plaintive answer to what he felt was the unreasonable demand from Rainald that he write within one week an epic recounting the Emperor's campaign in Italy.

[33] The Archpoet's poems are known for appearing "intensely personal":[15] he features in almost all of them, and deals in an outspoken manner with intimate subjects such as his material (e.g. poverty, wandering) and spiritual (e.g. distress, anger, love) condition, his flawed and sinful nature, his wishes and aspirations.

[34] Yet far from falling into mere lyricism or honest confidence, they are often undermined by subtle sarcasm and disguised mockery, fitting with the persona the Archpoet seems to have created for himself as a free-spirited, vagabond hedonist, unrepentant in his propensity to overindulge and unblushing in the judgment of his self-worth.