Second Opium War

The alliance then moved north to demand a treaty from the Qing court, and on 20 May 1858, captured the Taku Forts, seized Tianjin, and threatened the imperial capital Beijing.

However, the Xianfeng Emperor refused to ratify the treaty, after which the Qing general Sengge Rinchen restarted the war with the British and French that month.

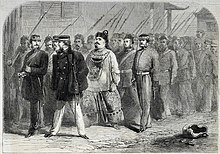

As the alliance's forces advanced toward Beijing, consul Parkes and a number of British and French officers were captured as hostages, and some were tortured or murdered.

The emperor and his entourage fled to Rehe, while Prince Gong stayed to conduct the negotiations, signing the Convention of Peking with the alliance on 24 October 1860, thus ratifying the Treaty of Tientsin and bringing the Second Opium War to an end.

[12][13][14] Between the two wars, repeated acts of aggression against British subjects led in 1847 to the Expedition to Canton which assaulted and took, by a coup de main, the forts of the Bocca Tigris resulting in the spiking of 879 guns.

In an effort to expand its privileges in China, Britain demanded that the Qing authorities renegotiate the Treaty of Nanjing (signed in 1842), citing its most favoured nation status.

Its captain, Thomas Kennedy, who was aboard a nearby vessel at the time, reported seeing Chinese marines pull the British flag down from the ship.

[17] The British consul in Canton, Harry Parkes, contacted Ye Mingchen, imperial commissioner and Viceroy of Liangguang, to demand the immediate release of the crew, and an apology for the alleged insult to the flag.

[19][page needed] On 3 March 1857, the British government lost a Parliamentary vote regarding the Arrow incident and what had taken place at Canton to the end of the previous year.

[21][page needed] In April, the British government asked the United States of America and Russia if they were interested in alliances, but both parties rejected the offer.

[citation needed] France joined the British action against China, prompted by complaints from their envoy, Baron Jean-Baptiste-Louis Gros, over the execution of a French missionary, Auguste Chapdelaine,[22] by Chinese local authorities in Guangxi province, which at that time was not open to foreigners.

[19][page needed][24] The remaining crew of the Arrow were then released, with no apology from Viceroy Ye Mingchen who also refused to honour the treaty terms.

The British House of Commons on 3 March passed a resolution by 263 to 249 against the Government saying: That this House has heard with the concern of the conflicts which have occurred between the British and Chinese authorities on the Canton River; and, without expressing an opinion as to the extent to which the Government of China may have afforded this country cause of complaint respecting the non-fulfilment of the Treaty of 1842, this House considers that the papers which have been laid on the table fail to establish satisfactory grounds for the violent measures resorted to at Canton in the late affair of the Arrow, and that a Select Committee be appointed to inquire into the state of our commercial relations with China.

[citation needed] The Chinese issue figured prominently in the election, at which Palmerston won an increased majority, silencing the voices within the Whig faction who supported China.

[citation needed] In June 1858, shortly after the Qing imperial court agreed to the disadvantageous treaties, hawkish ministers prevailed upon the Xianfeng Emperor to resist Western encroachment.

A British naval force with 2,200 troops and 21 ships, under the command of Admiral Sir James Hope, sailed north from Shanghai to Tianjin with newly appointed Anglo-French envoys for the embassies in Beijing.

Sengge Rinchen replied that the Anglo-French envoys might land up the coast at Beitang and proceed to Beijing but he refused to allow armed troops to accompany them to the Chinese capital.

Low tide and soft mud prevented their landing, however, and accurate fire from Sengge Rinchen's cannons sank four gunboats and severely damaged two others.

American Commodore Josiah Tattnall III, though under orders to maintain neutrality, declared "blood is thicker than water", and provided covering fire to protect the British convoy's retreat.

The failure to take the Taku Forts was a blow to British prestige, and anti-foreign resistance reached a crescendo within the Qing imperial court.

[32] Once the Indian Mutiny was finally quelled, Sir Colin Campbell, commander-in-chief in India, was free to amass troops and supplies for another offensive in China.

One observer reported that the "Chinese coolies", as he called them, "renegades though they were, served the British faithfully and cheerfully... At the assault of the Peiho Forts in 1860 they carried the French ladders to the ditch, and, standing in the water up to their necks, supported them with their hands to enable the storming party to cross.

It was not usual to take them into action; they, however, bore the dangers of a distant fire with great composure, evincing a strong desire to close with their compatriots, and engage them in mortal combat with their bamboos.

[36][page needed] The prisoners had been tortured by having their limbs bound with rope until their flesh was lacerated and became infected with maggots, and by having dung and dirt forced into their throats.

[37] On 21 September, at Baliqiao (Eight Mile Bridge), Sengge Rinchen's 10,000 troops, including the elite Mongol cavalry, were annihilated after doomed frontal charges against concentrated firepower of the Anglo-French forces.

[36]: 276 With the Qing army devastated, the Xianfeng Emperor fled the capital and left behind his brother, Prince Gong, to take charge of peace negotiations.

The destruction of the Forbidden City was discussed, as proposed by Lord Elgin, to discourage the Qing Empire from using kidnapping as a bargaining tool, and to exact revenge on the mistreatment of their prisoners.

In a letter, he explained that the burning of the palace was the punishment "which would fall, not on the people, who may be comparatively innocent, but exclusively on the Emperor, whose direct personal responsibility for the crime committed is established".

[43][page range too broad][44] The British, French and—thanks to the schemes of Ignatiev—the Russians were all granted a permanent diplomatic presence in Beijing (something the Qing Empire resisted to the very end as it suggested equality between China and the European powers).

[citation needed] The content of the Convention of Beijing included: Two weeks later, Ignatiev forced the Qing government to sign a "Supplementary Treaty of Peking", which ceded the Maritime Provinces east of the Ussuri River (forming part of Outer Manchuria) to the Russians, who went on to found the port of Vladivostok between 1860 and 1861.