Art of memory

[2] It has existed as a recognized group of principles and techniques since at least as early as the middle of the first millennium BCE,[3] and was usually associated with training in rhetoric or logic, but variants of the art were employed in other contexts, particularly the religious and the magical.

[2] It has been suggested that the art of memory originated among the Pythagoreans or perhaps even earlier among the ancient Egyptians, but no conclusive evidence has been presented to support these claims.

[6] The most common account of the creation of the art of memory centers around the story of Simonides of Ceos, a famous Greek poet, who was invited to chant a lyric poem in honor of his host, a nobleman of Thessaly.

When Cicero and Quintilian were revived after the 13th century, humanist scholars understood the language of these ancient writers within the context of the medieval traditions they knew best, which were profoundly altered by monastic practices of meditative reading and composition.

[9] Saint Thomas Aquinas was an important influence in promoting the art when, in following Cicero's categorization, he defined it as a part of Prudence and recommended its use to meditate on the virtues and to improve one's piety.

[13] Perhaps following the example of Metrodorus of Scepsis, vaguely described in Quintilian's Institutio oratoria, Giordano Bruno, a defrocked Dominican, used a variation of the art in which the trained memory was based in some fashion upon the zodiac.

[17] However, this transition was not without its difficulties, and during this period the belief in the effectiveness of the older methods of memory training (to say nothing of the esteem in which its practitioners were held) steadily became occluded.

[19] One explanation for the steady decline in the importance of the art of memory from the 16th to the 20th century is offered by the late Ioan P. Culianu, who argued that it was suppressed during the Reformation and Counter-Reformation when Protestants and reactionary Catholics alike worked to eradicate pagan influence and the lush visual imagery of the Renaissance.

[20] Whatever the causes, in keeping with general developments, the art of memory eventually came to be defined primarily as a part of Dialectics, and was assimilated in the 17th century by Francis Bacon and René Descartes into the curriculum of Logic, where it survives to this day as a necessary foundation for the teaching of Argument.

All the rhetorical textbooks contain detailed advice on declamatory gesture and expression; this underscores the insistence of Aristotle, Avicenna, and other philosophers, on the primacy and security for memory of the visual over all other sensory modes, auditory, tactile, and the rest.

And we shall do so if we establish similitudes as striking as possible; if we set up images that are not many or vague but active; if we assign to them exceptional beauty or singular ugliness; if we ornament some of them, as with crowns or purple cloaks, so that the similitude may be more distinct to us; or if we somehow disfigure them, as by introducing one stained with blood or soiled with mud and smeared with red paint, so that its form is more striking, or by assigning certain comic effects to our images, for that, too, will ensure our remembering them more readily.

Carruthers discusses this in the context of the way in which the trained medieval memory was thought to be intimately related with the development of prudence or moral judgement.

It is based on the use of places (Latin loci), which were memorized by practitioners as the framework or ordering structure that would 'contain' the images or signs 'placed' within it to record experience or knowledge.

Real physical locations were apparently commonly used as the basis of memory places, as the author of the Ad Herennium suggests it will be more advantageous to obtain backgrounds in a deserted than in a populous region, because the crowding and passing to and fro of people confuse and weaken the impress of the images, while solitude keeps their outlines sharp.

He provides the following famous example of a likeness based upon subject: Often we encompass the record of an entire matter by one notation, a single image.

For example, the prosecutor has said that the defendant killed a man by poison, has charged that the motive for the crime was an inheritance, and declared that there are many witnesses and accessories to this act.

However primary sources show that from very early in the development of the art, non-physical or abstract locations and/or spatial graphics were employed as memory 'places'.

Some researchers (L.A. Post and Yates) believe it likely that Metorodorus organized his memory using places based in some way upon the signs of the zodiac.

[36] This makes it clear that though the architectural mnemonic with its buildings, niches and three-dimensional images was a major theme of the art as practiced in classical times, it often employed signs or notae and sometimes even non-physical imagined spaces.

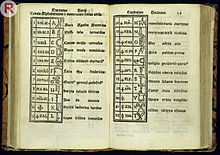

Examples of the development of the potential inherent in the graphical mnemonic include the lists and combinatory wheels of the Majorcan Ramon Llull.

[37] She goes on to suggest It may have been out of this atmosphere that there was formed a tradition which, going underground for centuries and suffering transformations in the process, appeared in the Middle Ages as the Ars Notoria, a magical art of memory attributed to Apollonius or sometimes to Solomon.

The practitioner of the Ars Notoria gazed at figures or diagrams curiously marked and called 'notae' whilst reciting magical prayers.

[39] If such an assessment is correct, it suggests that the use of text to recollect memories was, for medieval practitioners, merely a variant of techniques employing notae, images and other non-textual devices.

The 'method of loci' (plural of Latin locus for place or location) is a general designation for mnemonic techniques that rely upon memorized spatial relationships to establish, order and recollect memorial content.

[40] O'Keefe and Nadel refer to "'the method of loci', an imaginal technique known to the ancient Greeks and Romans and described by Yates (1966) in her book The Art of Memory as well as by Luria (1969).

In this technique the subject memorizes the layout of some building, or the arrangement of shops on a street, or a video game,[41][42] or any geographical entity which is composed of a number of discrete loci.

In some cases it refers broadly to what is otherwise known as the art of memory, the origins of which are related, according to tradition, in the story of Simonides of Ceos: and the collapsing banquet hall discussed above.

"[46] Skoyles and Sagan indicate that "an ancient technique of memorization called Method of Loci, by which memories are referenced directly onto spatial maps" originated with the story of Simonides.

[50] In other cases the designation is generally consistent, but more specific: "The Method of Loci is a Mnemonic Device involving the creation of a Visual Map of one's house.

"[51] This term can be misleading: the ancient principles and techniques of the art of memory, hastily glossed in some of the works just cited, depended equally upon images and places.