Arthropod

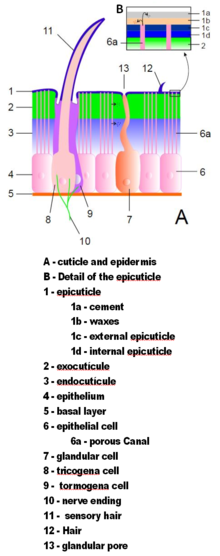

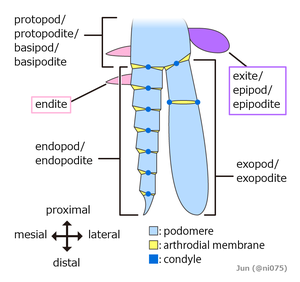

They possess an exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (metameric) segments, and paired jointed appendages.

Similarly, their reproduction and development are varied; all terrestrial species use internal fertilization, but this is sometimes by indirect transfer of the sperm via an appendage or the ground, rather than by direct injection.

The group is generally regarded as monophyletic, and many analyses support the placement of arthropods with cycloneuralians (or their constituent clades) in a superphylum Ecdysozoa.

[27][1] The origin of the name has been the subject of considerable confusion, with credit often given erroneously to Pierre André Latreille or Karl Theodor Ernst von Siebold instead, among various others.

Calcification of the endosternite, an internal structure used for muscle attachments, also occur in some opiliones,[34] and the pupal cuticle of the fly Bactrocera dorsalis contains calcium phosphate.

[40] The largest are species in the class Malacostraca, with the legs of the Japanese spider crab potentially spanning up to 4 metres (13 ft)[41] and the American lobster reaching weights over 20 kg (44 lbs).

[39] Arthropods also have two body elements that are not part of this serially repeated pattern of segments, an ocular somite at the front, where the mouth and eyes originated,[39][44] and a telson at the rear, behind the anus.

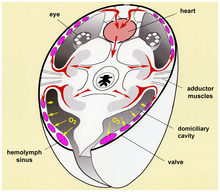

The four major groups of arthropods – Chelicerata (sea spiders, horseshoe crabs and arachnids), Myriapoda (symphylans, pauropods, millipedes and centipedes), Pancrustacea (oligostracans, copepods, malacostracans, branchiopods, hexapods, etc.

The strong, segmented limbs of arthropods eliminate the need for one of the coelom's main ancestral functions, as a hydrostatic skeleton, which muscles compress in order to change the animal's shape and thus enable it to move.

[63] Tracheae, systems of branching tunnels that run from the openings in the body walls, deliver oxygen directly to individual cells in many insects, myriapods and arachnids.

[69] On the other hand, the relatively large size of ommatidia makes the images rather coarse, and compound eyes are shorter-sighted than those of birds and mammals – although this is not a severe disadvantage, as objects and events within 20 cm (8 in) are most important to most arthropods.

[72] Although meiosis is a major characteristic of arthropods, understanding of its fundamental adaptive benefit has long been regarded as an unresolved problem,[73] that appears to have remained unsettled.

[70] Based on the distribution of shared plesiomorphic features in extant and fossil taxa, the last common ancestor of all arthropods is inferred to have been as a modular organism with each module covered by its own sclerite (armor plate) and bearing a pair of biramous limbs.

[83] Small arthropods with bivalve-like shells have been found in Early Cambrian fossil beds dating 541 to 539 million years ago in China and Australia.

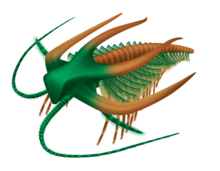

[89][6][46] Re-examination in the 1970s of the Burgess Shale fossils from about 505 million years ago identified many arthropods, some of which could not be assigned to any of the well-known groups, and thus intensified the debate about the Cambrian explosion.

[94] The purported pancrustacean/crustacean affinity of some cambrian arthropods (e.g. Phosphatocopina, Bradoriida and Hymenocarine taxa like waptiids)[95][96][97] were disputed by subsequent studies, as they might branch before the mandibulate crown-group.

[99] Arthropods possessed attributes that were easy coopted for life on land; their existing jointed exoskeletons provided protection against desiccation, support against gravity and a means of locomotion that was not dependent on water.

[116][117] For example, Graham Budd's analyses of Kerygmachela in 1993 and of Opabinia in 1996 convinced him that these animals were similar to onychophorans and to various Early Cambrian "lobopods", and he presented an "evolutionary family tree" that showed these as "aunts" and "cousins" of all arthropods.

The earliest known arthropods ate mud in order to extract food particles from it, and possessed variable numbers of segments with unspecialized appendages that functioned as both gills and legs.

Nematoida (nematodes and close relatives) Scalidophora (priapulids and Kinorhyncha, and Loricifera) Onychophorans Tardigrades Chelicerates †Euthycarcinoids Myriapods Crustaceans Hexapods Relationships of Ecdysozoa to each other and to annelids, etc.,[122][failed verification] including euthycarcinoids[123]Higher up the "family tree", the Annelida have traditionally been considered the closest relatives of the Panarthropoda, since both groups have segmented bodies, and the combination of these groups was labelled Articulata.

In the 1990s, molecular phylogenetic analyses of DNA sequences produced a coherent scheme showing arthropods as members of a superphylum labelled Ecdysozoa ("animals that moult"), which contained nematodes, priapulids and tardigrades but excluded annelids.

[124][122] giant lobopodians † gilled lobopodians † Radiodonta † Chelicerata Megacheira † Artiopoda † Isoxyida † Mandibulata Aside from the four major living groups (crustaceans, chelicerates, myriapods and hexapods), a number of fossil forms, mostly from the early Cambrian period, are difficult to place taxonomically, either from lack of obvious affinity to any of the main groups or from clear affinity to several of them.

[126] The clade is defined by important changes to the structure of the head region such as the appearance of a differentiated deutocerebral appendage pair, which excludes more basal taxa like radiodonts and "gilled lobopodians".

[125] The phylum Arthropoda is typically subdivided into four subphyla, of which one is extinct:[130] The phylogeny of the major extant arthropod groups has been an area of considerable interest and dispute.

[134] The following cladogram shows the internal relationships between all the living classes of arthropods as of the late 2010s,[137][138][139] as well as the estimated timing for some of the clades:[140] Pycnogonida Xiphosura Arachnida Chilopoda Symphyla Pauropoda Diplopoda Ostracoda Mystacocarida Ichthyostraca Copepoda Malacostraca Tantulocarida Thecostraca Cephalocarida Branchiopoda Remipedia Collembola Protura Diplura Insecta Crustaceans such as crabs, lobsters, crayfish, shrimp, and prawns have long been part of human cuisine, and are now raised commercially.

[142][143] Cooked tarantulas are considered a delicacy in Cambodia,[144][145][146] and by the Piaroa Indians of southern Venezuela, after the highly irritant hairs – the spider's main defense system – are removed.

The blood of horseshoe crabs contains a clotting agent, Limulus Amebocyte Lysate, which is now used to test that antibiotics and kidney machines are free of dangerous bacteria, and to detect spinal meningitis.

Forensic entomology uses evidence provided by arthropods to establish the time and sometimes the place of death of a human, and in some cases the cause.

[159] The relative simplicity of the arthropods' body plan, allowing them to move on a variety of surfaces both on land and in water, have made them useful as models for robotics.

[169] Increasing arthropod resistance to pesticides has led to the development of integrated pest management using a wide range of measures including biological control.