Artificial gravity

[2] Rotational simulated gravity has been proposed as a solution in human spaceflight to the adverse health effects caused by prolonged weightlessness.

[3] However, there are no current practical outer space applications of artificial gravity for humans due to concerns about the size and cost of a spacecraft necessary to produce a useful centripetal force comparable to the gravitational field strength on Earth (g).

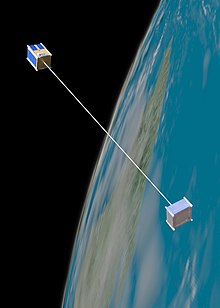

The Gemini 11 mission attempted in 1966 to produce artificial gravity by rotating the capsule around the Agena Target Vehicle to which it was attached by a 36-meter tether.

They were able to generate a small amount of artificial gravity, about 0.00015 g, by firing their side thrusters to slowly rotate the combined craft like a slow-motion pair of bolas.

However, criticism of those methods lies in the fact that they do not fully eliminate health problems and require a variety of solutions to address all issues.

[1] Especially in a modern-day six-month journey to Mars, exposure to artificial gravity is suggested in either a continuous or intermittent form to prevent extreme debilitation to the astronauts during travel.

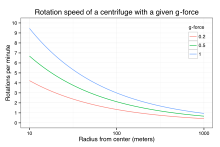

One of the realistic methods of creating artificial gravity is the centrifugal effect caused by the centripetal force of the floor of a rotating structure pushing up on the person.

Linear acceleration is another method of generating artificial gravity, by using the thrust from a spacecraft's engines to create the illusion of being under a gravitational pull.

[26] Similarly, a hypothetical space travel using constant acceleration of 1 g for one year would reach relativistic speeds and allow for a round trip to the nearest star, Proxima Centauri.

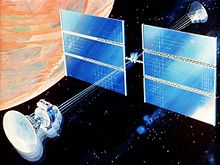

Two examples of this long-duration, low-thrust, high-impulse propulsion that have either been practically used on spacecraft or are planned in for near-term in-space use are Hall effect thrusters and Variable Specific Impulse Magnetoplasma Rockets (VASIMR).

They are thus ideally suited for long-duration firings which would provide limited amounts of, but long-term, milli-g levels of artificial gravity in spacecraft.

[citation needed] In a number of science fiction plots, acceleration is used to produce artificial gravity for interstellar spacecraft, propelled by as yet theoretical or hypothetical means.

This effect of linear acceleration is well understood, and is routinely used for 0 g cryogenic fluid management for post-launch (subsequent) in-space firings of upper stage rockets.

Eugene Podkletnov, a Russian engineer, has claimed since the early 1990s to have made such a device consisting of a spinning superconductor producing a powerful "gravitomagnetic field."

In 2006, a research group funded by ESA claimed to have created a similar device that demonstrated positive results for the production of gravitomagnetism, although it produced only 0.0001 g.[33]