Physiological effects in space

This normal adaptive response to the microgravity environment may become a liability resulting in increased risk of an inability or decreased efficiency in crewmember performance of physically demanding tasks during extravehicular activity (EVA) or upon return to Earth.

Additional observations included the presence of postflight orthostatic intolerance that was still present for up to 50 hours after landing in soe crewmembers, a decrease in red cell mass of 5 – 20% from preflight levels, and radiographic indications of bone demineralization in the calcaneus.

No significant decrements in performance of mission objectives were noted and no specific measurements of muscle strength or endurance were obtained that compared preflight, in-flight and postflight levels.

Essential to the successful completion of the Apollo Program was the requirement for some crew members to undertake long and strenuous periods of extravehicular activity (EVA) on the lunar surface.

This, investigators were left with only the possibility to conduct pre-flight and post-flight exercise response studies and to assume that these findings reflected alterations of cardiopulmonary and skeletal muscle function secondary to microgravity exposure.

During each test, workload, heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory gas exchange (oxygen consumption, carbon dioxide production, and minute volume) measurements were made.

The bicycle ergometer proved to be an excellent machine for aerobic exercise and cardiovascular conditioning, but it was not capable of developing either the type or level of forces needed to maintain strength for walking under 1G.

The Space Shuttle Program and, in particular, EDOMP has provided a great deal of knowledge about the effects of spaceflight on human physiology and specifically on alterations in skeletal muscle mass, strength, and function.

However, the data provided by MRI volume studies indicate that not all crewmembers, despite utilization of various exercise countermeasures, escape the loss in muscle mass that has been documented during most of the history of U.S. human spaceflight since Project Mercury.

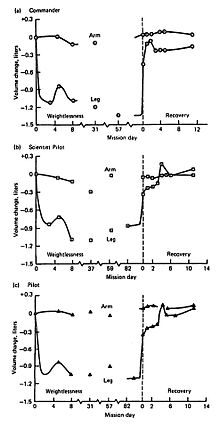

The major contribution of the joint U.S./Russian effort on the Mir space station relevant to the current risk topic was the first use of MRI to investigate volume changes in the skeletal muscles of astronauts and cosmonauts exposed to long-duration spaceflight.

ISS crewmembers, under the supervision of their crew surgeons, participate in a postflight exercise program implemented by certified trainers who comprise the Astronaut Strength, Conditioning and Rehabilitation (ASCR) group at Johnson Space Center.

This susceptibility may reflect the almost continuous levels of self-generated (active) and environmentally generated (reactive) mechanical loading to which these muscles are exposed under normal Earth gravity.

Although no perfect simulation of crew activities and the microgravity environment can be adequately achieved, Adams and colleagues have suggested that bed rest is an appropriate model of spaceflight for studying skeletal muscle physiologic adaptations and countermeasures.

[57][59][60] Dry immersion, a whole-body-unloading paradigm with the added advantage of mimicking the reduced proprioceptive input encountered during spaceflight, also brings about reductions in muscle volume, strength, endurance, electrical activity, and tone.

[73] A similar reduction in the activity of citrate synthase, but not phosphofructokinase, has been detected in the vastus lateralis, indicating a significant impairment of the oxidative capacity in this muscle after unilateral limb suspension.

[49] Although not specifically reported, subjects in an 89-day bed rest trial [50] experienced significant reductions in isokinetic torque in the lower body, with the greatest losses in the knee extensors (−35%).

[50] After 55 days of bed rest, Berg et al. reported that a 22% reduction in isometric hip extension occurred, although the extensor muscles in the gluteal region decreased in volume by only 2%.

[79] The authors reported no explanation for this discrepancy between the proportion of reduced strength relative to the loss of mass, and also stated that no previous studies in the literature had made these concurrent strength/volume measurements in the hip musculature.

Additionally, human space travelers are often not well hydrated, have a 10–15% decrease in intravascular fluid (plasma) volume, and may lose both their preflight muscular and cardiovascular fitness levels as well as their thermoregulatory capabilities.

During spaceflight, their ankles appear to assume a plantar flexed position that may reduce the passive tension (force) imposed on the triceps surae group, of which the anti-gravity slow-twitch soleus muscle is a chief component.

Thus, rodent motor skills and basic locomotor capability have less fidelity and capacity during posture maintenance and locomotion during the early stages of recovery; however, by 9 days after flight the activity properties return to those seen in normal conditions.

[96] Accompanying the atrophy process noted above are the important observations that many (but not all) of the slow fibers in primarily antigravity-type muscles (such as Soleus and VI) are also induced to express fast myosin isoforms.

However, observations suggest that during the first 5–6 hours after spaceflight (the earliest time point at which the animals can be accessed), edema occurs in the target anti-gravity muscles such as the soleus and the adductor longus (AL).

Riley has proposed that the reason for the differential response between the two muscle groups is that weakened animals have altered their posture and gait so that eccentric stress is placed on the AL, resulting in some fiber damage.

These included eccentric-like lesioned sarcomeres, myofibrillar disruptions, edema, and evidence of macrophage activation and monocyte infiltration (known markers of injury-repair processes in the muscle) within target myofibers.

It is apparent that the best strategy to accomplish this task is via a vigorous countermeasure program that provides a high level of mechanical stress to prevent the imbalance in protein expression that occurs when the muscle is insufficiently loaded for significant periods without an intervening anabolic stimulus.

[137] Because of the difficulties in developing such a mathematical model based on the complexities and variables of human physiology operating in the unusual environment of microgravity, the utility of this approach, although reasonable, remains to be proven.

However, capability to provide sufficient exercise capacity during the Martian outpost phase is essential in preparing the crew for a long-duration exposure to microgravity on the transit back to Earth.

Gaps in our knowledge have prevented us from implementing a countermeasures program that will fully mitigate the risks of losing muscle mass, function, and endurance during exposure to the microgravity of spaceflight, particularly during long-duration missions.

The major knowledge gaps that must be addressed by future research to mitigate this risk of loss of skeletal muscle mass, function, and endurance include the following: A mission to Mars or another planet or asteroid within the Solar System is not beyond possibility within the next two decades.