Artillery fuze

A fuze is a device that initiates an explosive function in a munition, most commonly causing it to detonate or release its contents, when its activation conditions are met.

[1] It was not until around the middle of the 18th century that it was realised that the windage between ball and barrel allowed the flash from the propelling charge to pass around the shell.

At this time fuzes were made of beech wood, bored out and filled with powder and cut to the required length.

Progress was not possible until the discovery of mercury fulminate in 1800, leading to priming mixtures for small arms patented by the Rev Alexander Forsyth, and the copper percussion cap in 1818.

British inventor Colonel Edward Boxer of the Royal Artillery suggested a better way: wooden fuze cones with a central powder channel and holes drilled every 2/10th of an inch.

[7] However, in 1855 Armstrong produced his rifled breech loading (RBL) gun, which was introduced into British service in 1859.

It was the prototype of the T&P fuzes used in the 20th century, although initially it was used only with naval segment shells, and it took some time for the army to adopt it for shrapnel.

Artillery fuzes were sometimes specific to particular types of gun or howitzer due to their characteristics, notable differences in muzzle velocity and hence the sensitivity of safety and arming mechanisms.

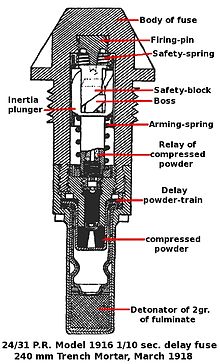

However, smoothbore mortars constrain the choice of safety and arming mechanisms because there is no centrifugal force and muzzle velocities are relatively low.

These contents may be lethal, such as the now-obsolete shrapnel shell or modern sub-munitions, or non-lethal such as canisters containing a smoke compound or a parachute flare.

Some older types of fuze also had safety features such as pins or caps removed by the user before loading the shell into the breech.

Examples include: Modern safety and arming devices are part of an overall fuze design that meets insensitive munitions requirements.

War stocks in western armies are now predominantly 'multi-function' offering a choice of several ground and airburst functions.

For example, the firing pin and detonator may be close to the nose with a long flash tube to the booster (typical in US designs), or there might instead be a long firing pin to a detonator close to the booster and a short flash tube (typical in British designs).

For example, the later WWII German Navy armor-piercing projectile base fuzes ("Bodenzunder") had such fuzes of several kinds, with the weighted firing pin and the explosive detonator pellet both free to move, held apart only by friction or a light spring, after arming in flight by removing a series of rotating shutters locking them in place before firing the projectile.

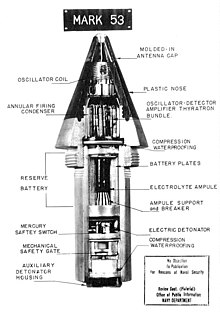

During World War 2 radio proximity fuzes were introduced, initially for use against aircraft, where they proved far superior to mechanical time, and at the end of 1944 for field artillery.

One exception was the 1950s design US 203 mm (8 in) nuclear shell (M422) that had a triple-deck mechanical time base fuze.

The problem with igniferous fuzes was that, though good enough for flat trajectory shrapnel (ranges were relatively short by later standards) or high bursting carrier shells, they were imprecise and erratic.

Britain in particular encountered great difficulty in achieving consistency early in World War I (1914 and 1915) with its then-obsolescent gunpowder-train time fuzes for anti-aircraft fire against targets at altitudes up to 6,000 metres (20,000 ft).

[11] Britain finally switched to mechanical (i.e. clockwork) time fuzes just after World War I, which solved this problem.

Residual stocks of igniferous fuzes lasted for many years after World War 2 with smoke and illuminating shells.

Mechanical time fuzes were good enough for field artillery to achieve the effective HE height of burst of about 10 metres above the ground.

[15] During 1940–42 a private venture initiative by Pye Ltd, a leading British wireless manufacturer, worked on the development of a radio proximity fuze.

It has the advantage of inherent safety and not requiring any internal driving force but depended on muzzle velocity and rifling pitch.

However, they were cheaper than older proximity fuzes and the cost of adding electronic functions was marginal, so they were more widely issued.

For example, Junghans DM84U provides delay, super quick, time (up to 199 seconds), two proximity heights of burst and five depths of foliage penetration.

Initial developments were the United States 'Seek and Destroy Armour' (SADARM) in the 1980s using sub-munitions ejected from a 203 mm (8.0 in) carrier shell.

These sensor fuzes typically use millimetric radar to recognise a tank, aim the sub-munition at it, and fire an explosively formed penetrator from above.

Naval and anti-aircraft artillery started using analogue computers before World War 2, connected to the guns to automatically aim them.

This was particularly important for anti-aircraft guns that were aiming ahead of their target and so needed a regular, predictable rate of fire.