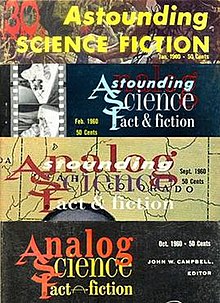

Analog Science Fiction and Fact

The new editor was F. Orlin Tremaine, who soon made Astounding the leading magazine in the nascent pulp science fiction field, publishing well-regarded stories such as Jack Williamson's Legion of Space and John W. Campbell's "Twilight".

The financial difficulties led Clayton to start alternating the publication of his magazines, and he switched Astounding to a bimonthly schedule with the June 1932 issue.

They already had two pulp titles that occasionally ventured into the field: The Shadow, which had begun in 1931 and was tremendously successful, with a circulation over 300,000; and Doc Savage, which had been launched in March 1933.

Astounding returned to pulp-size in mid-1943 for six issues, and then became the first science fiction magazine to switch to digest size in November 1943, increasing the number of pages to maintain the same total word count.

[26] The following year, Campbell finally achieved his goal of getting rid of the word "Astounding" in the magazine's title, changing it to Analog Science Fact/Science Fiction.

[7] Bova planned to stay for five years, to ensure a smooth transition after Campbell's sudden death; the salary was too low for him to consider remaining indefinitely.

The policy was probably worked out between Tremaine and Desmond Hall, his assistant editor, in an attempt to give Astounding a clear identity in the market that would distinguish it from both the existing science fiction magazines and the hero pulps, such as The Shadow, that frequently used sf ideas.

He serialized Charles Fort's Lo!, a nonfiction work about strange and inexplicable phenomena, in eight parts between April and November 1934, in an attempt to stimulate new ideas for stories.

Ashley describes the interior artwork as "entrancing, giving hints of higher technology without ignoring the human element", and singles out the work of Elliot Dold as particularly impressive.

Tremaine's slow responses to submissions discouraged new authors, although he could rely on regular contributors such as Jack Williamson, Murray Leinster, Raymond Gallun, Nat Schachner, and Frank Belknap Long.

Howard V. Brown had done almost every cover for the Street & Smith version of Astounding, and Campbell asked him to do an astronomically accurate picture of the Sun as seen from Mercury for the February 1938 issue.

The list of names included established authors like L. Ron Hubbard, Clifford Simak, Jack Williamson, L. Sprague de Camp, Henry Kuttner, and C.L.

[42] Jack Williamson's "Legion of Time", described by author and editor Lin Carter as "possibly the greatest single adventure story in science fiction history",[47] began serialization in the following issue.

De Camp contributed a nonfiction article, "Language for Time Travelers", in the July issue, which also contained Hubbard's first science fiction sale, "The Dangerous Dimension".

[48] Heinlein rapidly became one of the most prolific contributors to Astounding, publishing three novels in the next two years: If This Goes On—, Sixth Column, and Methuselah's Children; and half a dozen short stories.

The September 1942 issue contained del Rey's "Nerves", which was one of the few stories to be ranked top by every single reader who voted in the monthly Analytical Laboratory poll; it dealt with the aftermath of an explosion at a nuclear plant.

Among those who remained, the key figures were van Vogt, Simak, Kuttner, Moore, and Fritz Leiber, all of whom were less oriented towards technology in their fiction than writers like Asimov or Heinlein.

[53][notes 1] Leiber's Gather, Darkness!, serialized in 1943, was set in a world where scientific knowledge is hidden from the masses and presented as magic; as with Kuttner and Moore, he was simultaneously publishing fantasies in Unknown.

It appeared in 1944, when the Manhattan Project was still not known to the public; Cartmill used his background in atomic physics to assemble a plausible story that had strong similarities to the real-world secret research program.

[56] In the late 1940s, both Thrilling Wonder and Startling Stories began to publish much more mature fiction than they had during the war, and although Astounding was still the leading magazine in the field, it was no longer the only market for the writers who had been regularly selling to Campbell.

Arthur C. Clarke's first story, "Loophole", appeared in the April 1946 Astounding, and another British writer, Christopher Youd, began his career with "Christmas Tree" in February 1949.

Other stories and articles were written by some of the most famous authors of the time: Asimov, Sturgeon, del Rey, van Vogt, de Camp, and the astronomer R. S.

[61] Campbell was deeply involved with the launch of Dianetics, publishing Hubbard's first article on it in Astounding in May 1950, and promoting it heavily in the months beforehand;[62][63] later in the decade he championed psionics and antigravity devices.

[64] In 1953, Campbell serialized Hal Clement's Mission of Gravity, described by John Clute and David Langford as "one of the best-loved novels in sf",[65] and in 1954 Tom Godwin's "The Cold Equations" appeared.

[69] Over his first few months some long-time readers sent in letters of complaint when they judged that Bova was not living up to Campbell's standards, particularly when sex scenes began to appear.

This was the first story in Haldeman's "Forever War" sequence; Campbell had rejected it, listing multiple reasons including the frequent use of profanity and the implausibility of men and women serving in combat together.

[30][75][76] The stable of fiction contributors remained largely unchanged from Bova's day, and included many names, such as Poul Anderson, Gordon R. Dickson, and George O. Smith, familiar to readers from the Campbell era.

The magazine thrived nevertheless, and though part of the increase in circulation during the early 1980s may have been due to Davis Publications' energetic efforts to increase subscriptions, Schmidt knew what his readership wanted and made sure they got it, commenting in 1985: "I reserve Analog for the kind of science fiction I've described here: good stories about people with problems in which some piece of plausible (or at least not demonstrably implausible) speculative science plays an indispensable role".

[77] Over the decades of Schmidt's editorship, many writers became regular contributors, including Arlan Andrews, Catherine Asaro, Maya Kaathryn Bohnhoff, Michael Flynn, Geoffrey A. Landis, Paul Levinson, Robert J. Sawyer, Charles Sheffield and Harry Turtledove.

In April 1965 the subtitle was reversed, so that the magazine became Analog Science Fiction & Fact, and it has remained unchanged since then, though it has undergone several stylistic and orthographic variations.